California drought, Australia floods: Two sides of La Niña amplified by climate change

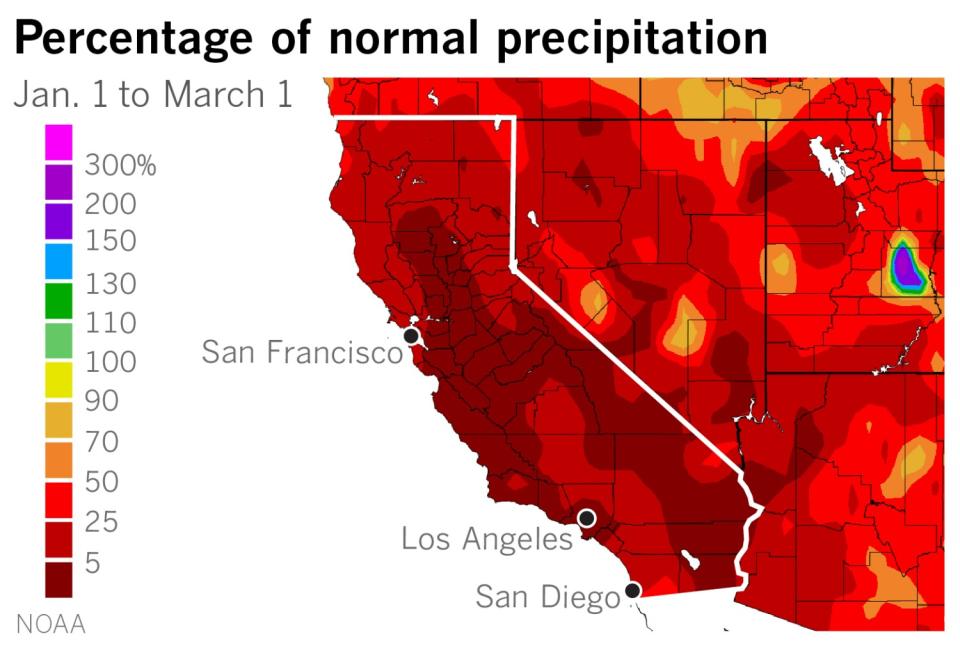

California just notched its driest January and February on record, sounding alarms about a third year of record drought.

Across the Pacific Ocean, thousands are fleeing record flooding in Australia. Officials in Brisbane reported 31 inches of rain in six days, and Jonathan Howe, a government meteorologist quoted by the Associated Press, called the amount of rainfall "astronomical."

Meanwhile, in the eastern Horn of Africa, prolonged drought is raising the frightening specter of famine for millions.

All of these are related as a multiyear La Niña event, amplified by the effects of climate change, brings consecutive years of drought to some parts of the world and torrential rain to others.

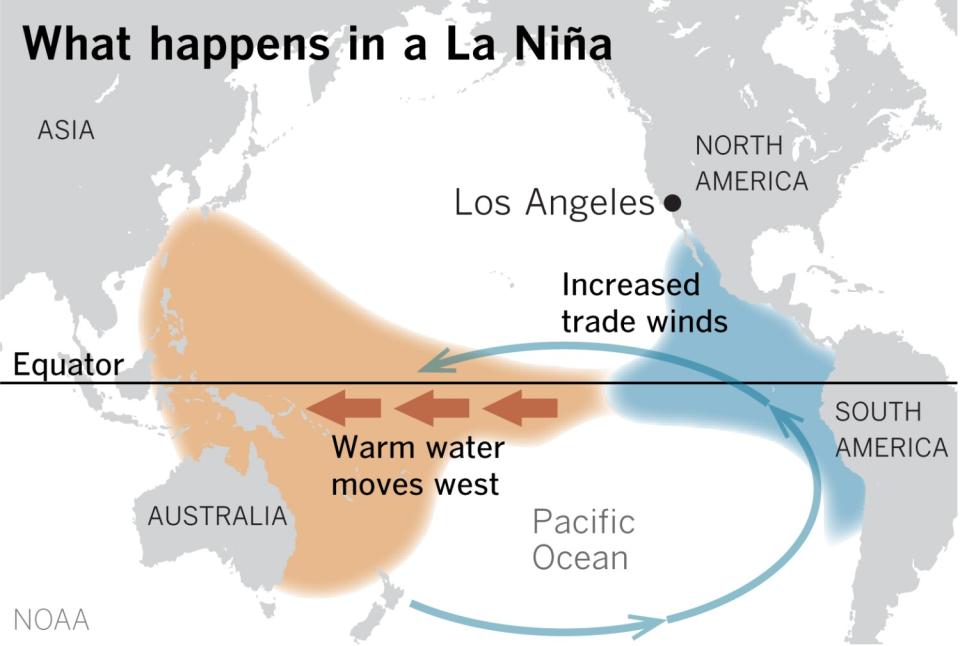

La Niña is part of a natural cycle in the Pacific Ocean that influences climate around the world and is often a factor in climate extremes. It is characterized by below-average sea surface temperatures in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific.

Trade winds normally blow from east to west over that region, pushing warm water toward the western Pacific. In the eastern Pacific, near South America, the action of these winds causes upwelling of cool water from the deep.

The difference in air temperature between the eastern and western tropical Pacific sets up a huge cycle called the Walker circulation, in which warm air rises in the west, north of Australia, travels east at upper levels of the atmosphere, then sinks as it cools near South America. This happens in the neutral or normal phase, which is in place more than half of the time.

When a La Niña event takes shape, the east-to-west trade winds strengthen, beefing up the pool of warm water in the western Pacific and causing more cooling in the eastern part of the tropical Pacific. The temperature differential between east and west is heightened, and the Walker circulation is stronger, perpetuating itself through a feedback loop and usually keeping the pattern in place for months or longer.

Rainfall generally decreases over the central and eastern tropical Pacific and increases over the western Pacific, Indonesia and the Philippines. That's because the warmer water in the western Pacific causes more evaporation, more clouds and more rain, as well as more tropical cyclones or typhoons.

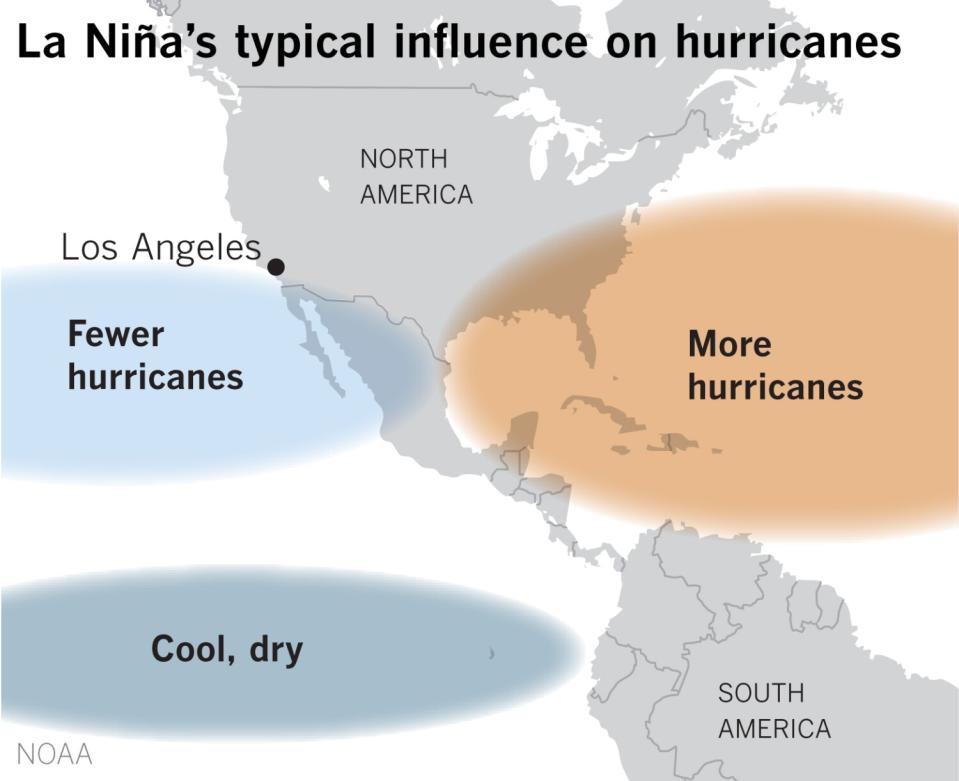

La Niñas usually weaken wind shear in the Caribbean and tropical Atlantic, contributing to increased hurricane activity in the Atlantic Basin. Both 2020 and 2021 were active hurricane seasons, with 2020 going down as the year with the most named storms of any season on record.

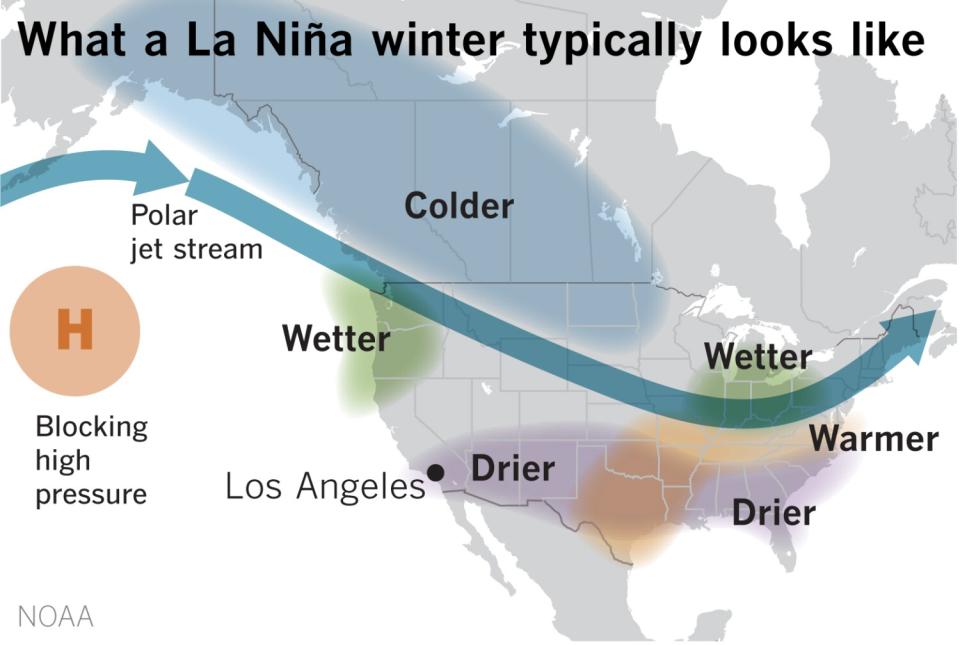

La Niñas are typically associated with colder, stormier-than-average conditions and increased precipitation across the northern parts of the United States, and warmer, drier and less stormy conditions in the southern portions of the country.

With the exception of an unusually wet December in California, this pattern appears to be playing out according to script for a second consecutive La Niña year.

The first two months of 2022, usually the wettest of the year, were the driest consecutive January and February on record in the Sierra Nevada, which normally serves as a natural cold storage for California's water. Typically, as the snowpack melts through the warm season, it fills the state's streams and reservoirs, supplying cities and farms.

La Niña's sibling and opposite is El Niño, during which the east-to-west trade winds weaken or even reverse. This allows the warmer tropical waters to move back eastward toward South America. The Walker circulation weakens, causing the trade winds to diminish.

As with La Niña, this pattern also perpetuates itself in a feedback loop. With the warm water now in the eastern tropical Pacific, the evaporation and rain formation shifts from west to east. El Niños often — but not always — lead to wet winters in California.

These are natural climate variations, but recent droughts, floods and heat waves suggest something has changed.

Human-caused climate change is amplifying the effects of natural variations around the globe. The United Nations' World Meteorological Organization documented a fivefold increase in weather and climate disasters over the last 50 years.

"This means longer and more intense heat waves, longer-duration droughts, larger and more costly wildfires and more devastating floods, such as those we have observed recently," climatologist Bill Patzert said.

According to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network, created in 1985 by the U.S. Agency for International Development, human-caused warming in the western Pacific has driven a large decline in East African rainfall since 1998, and these rainfall reductions are heightened during La Niña events.

"La Niña's reach, enhanced by climate change, is global," Patzert said. "Drought in California's Sierra Nevada mirrors the two-decade drought in the Horn of Africa."

While millions of humans experience food insecurity or starvation in Africa, those warming ocean temperatures are also threatening the largest living structure on the planet, Australia's 1,400-mile-long Great Barrier Reef. Bleaching, caused by a warming ocean, has imperiled the reef and its ecosystem.

Global warming is increasing the atmosphere's evaporative demand, essentially creating a thirstier atmosphere. This warmer, drier environment sucks more moisture out of plants and soils, reducing streams to trickles and reservoirs to empty, bathtub-ringed bowls.

The effect is to intensify droughts, turning cyclically dry conditions dire much more frequently. Vegetation is desiccated, and forests are vulnerable to pests, such as bark beetles, making fire seasons year-round affairs, not merely a threat during seasonal periods of dry offshore Santa Ana winds.

While California and the Southwest worry about the implications of a second consecutive no-show rainy season amid the region's driest 22-year period in 1,200 years, Australia is mobilizing its "Mud Army." Those are the volunteers who earned that name by helping out in the floods of 2011, which was also a La Niña year.

Floods and droughts are two facets of the same global La Niña climate event. But the different faces of the same event are being dangerously distorted and exaggerated by the carnival mirror of climate change.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.