How California’s home insurance crisis is trickling down to SLO County

When Cambria resident Brian Caserio had to switch his homeowner’s insurance to the California FAIR Plan earlier this year, it felt like the culmination of frustrations that started more than 25 years ago.

Caserio said keeping his home insured has become extremely expensive in recent years, as several major insurers have repeatedly raised their prices or pulled out from writing policies in California entirely.

When Caserio spoke with his insurance agent about the high rates, he got little in the way of good news on the future of the state’s insurance market.

“He pretty much burst my bubble and said there’s NO WAY I’d ever get out of the California FAIR Plan hell, and things were only going to get worse ... a lot worse,” Caserio told The Tribune in an email.

His agent was right. Most recently, State Farm and Allstate stopped writing new home insurance policies in the state, leaving many Californians like Caserio with fewer options for insuring their homes.

Here’s why insurance rates are so high — and why it’s harder to insure your house now than it was a year ago.

Residents in high risk areas paying a premium

Caserio’s property, which features a main house and smaller separate unit nestled in the woods of Cambria, was insured by Farmers Insurance 10 years ago but has bounced from insurer to insurer as rates have risen in recent years.

Caserio initially left Farmers after the insurer “radically raised” rates, leading him to look out of state for policies.

For a time, the strategy worked, but four years ago, his insurance policy on the main home was canceled by American Modern insurance.

Lexington Insurance, which insured the smaller unit, followed suit in early 2022, which Caserio said demonstrates the disparities between how different companies assess risk.

At the time of the cancellations, Caserio was paying $3,200 annually to insure the main home, and another $2,300 for the smaller home.

Since then, no other insurer has been able to cover Caserio’s property, so he’s had to turn to the California FAIR Plan, and has endured far higher rates as a result.

The California FAIR Plan is a private insurer controlled by insurance companies that provides coverage for individuals who cannot get coverage by conventional means regardless or risk level.

Under the FAIR Plan, Caserio’s rates have spiked to $4,500 per year for the main dwelling, while the second home’s prices have jumped to $3,500, he said.

“Keep in mind, each of the plans increases by a good 10% per year without explanation” under the FAIR Plan, Caserio said. “It feels like our issues with homeowner’s insurance started so long ago I can’t even remember how long it has been.”

Also, because the FAIR Plan only covers fire risk, Caserio said he’s also had to purchase supplemental policies of $1,500 and $900 per year for the main home and second unit, respectively, to fully cover each home.

All told, he’s paying $10,500 a year in home insurance premiums — nearly double what he was paying just a couple years ago, he said.

What should SLO County homeowners expect?

Janet Ruiz, director of strategic communications with the Insurance Information Institute, said the insurance industry is undergoing substantial changes as it adapts to the effects of climate change.

Ruiz said that since 2017, the industry has lost around 20 years of underwriting profit in California from wildfires and inflation.

That means the income being brought in from premiums has been outpaced by the rising cost to repair or fully rebuild homes lost to natural disasters, she said.

Ruiz said it was important to note most major insurers will continue renewing policies and have not pulled out of the state altogether.

For example, State Farm — which has a 21% share of the California home insurance market — will likely renew many existing policies so the company does not go insolvent, but it cannot tolerate any more risk, Ruiz said.

But with the risk of catastrophic wildfires now a way of life, Ruiz said the companies that are still writing home insurance policies in California are limiting the number to contain risk.

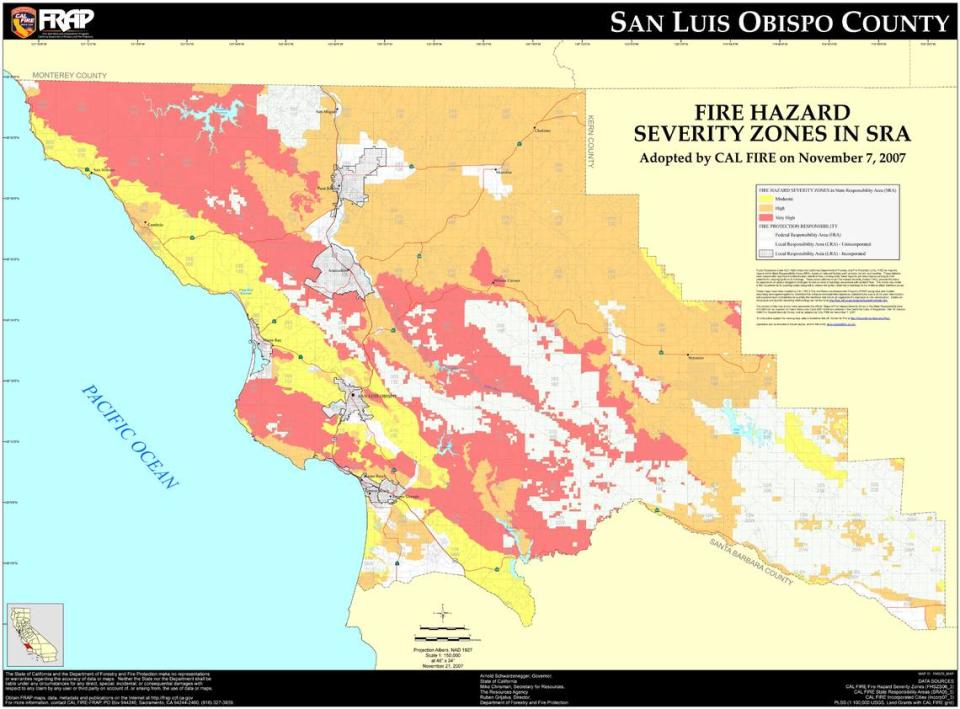

According to the California Office of the State Fire Marshal, some 12.5 million acres of the state are considered to be at a very high risk for wildfire. Another 10.6 million acres are considered high risk, while 7.9 million acres considered a moderate risk.

The cities of Atascadero, Morro Bay, Pismo Beach and San Luis Obispo are all located in very high fire hazard severity zones, according to the Office of the State Fire Marshal.

“Some (insurers) have non-renewed policies in certain areas that are at high risk for wildfires, and others have stopped driving business in specific areas,” Ruiz said. “We’ve seen recently in the last month a few companies have decided not to write any new business in California.”

Ruiz said the Department of Insurance must allow insurance companies to “charge the right premiums” if insurers have any chance of remaining in California.

Historically, California homeowners have largely paid lower premiums despite one of the highest costs to build a home in the country, Ruiz said.

That’s because until the recent explosion of devastating fires, the state had been less prone to regular, massive natural disasters than other regions of the country. It also has regulations that limit how much insurers can raise rates.

As a result, average home insurance policies in California cost around $1,400 a year, lower than the country’s average of around $1,700 per year, Ruiz said.

Compared to areas that experience tornadoes, which average rates of around $2,500 a year, or Florida, where hurricanes, flooding and rising sea levels push average rates to around $6,000 per year, Californians have usually paid relatively low home insurance rates, Ruiz said.

Ruiz said this high-risk, low-cost insurance market is the result of 1988’s Proposition 103, which requires insurers to get the Department of Insurance’s authorization prior to rate changes.

The Department of Insurance also does not allow for “forward modeling,” a practice in insurance that looks to predict future losses, and adjusts rates to reserve a surplus of money for those losses, Ruiz said.

“The Department of Insurance only allows insurance companies to do an average of the loss history over the last 20 years, and 20 years ago, we weren’t having big wildfires,” Ruiz said. “The wildfires have gotten quite a bit larger, and there are more people living in areas where they occur.”

What is making insurance so hard to get?

Erin Powers, a personal lines manager at Morris & Garritano Insurance in San Luis Obispo, said Caserio’s experience with rate hikes and the FAIR Plan will become more common among San Luis Obispo County homeowners.

Though some regional and locally based insurers such as Capital Insurance Group have seen a surge in business filling the gap from Allstate and State Farm, Powers said insurers are also facing more risk than ever, and are less likely to write new policies.

Farmers Insurance Group, USAA, Bamboo Insurance and Mercury Insurance are still writing new policies, but are likely trying to limit the number of new policies, Powers said.

“Based on what we’ve seen over the last six to eight months, I would not be surprised if others pull out of writing new business in California,” Powers said in an email to The Tribune.

Any insurer can choose to non-renew a policy, making risk and fire prevention measures all the more important for homeowners, Powers said.

Erich Schaefer, president of San Luis Obispo-based Schaefer Custom Homes, said it can cost anywhere between $500 and $700 per square foot to build a home in the county, and costs around 10% to 20% more to repair an existing structure.

That’s because the supply chain shortages that defined the construction industry since 2021 have kept material prices around 50% higher than normal, he said.

It’s a problem that has both slowed the production of new housing and has made repairing damage more difficult due to uncertainty over what materials will be available, he said.

“It really brings into sharp focus the dilemma of people on a fixed income with a fixed asset base that they’ve stashed away their whole lives, in order to be able to have their dream home, or maybe just an average home,” Schaefer told The Tribune. “Now, their hopes are dashed on the rocks.”

Homes like Caserio’s, which is built near open space in a rural area with plenty of fuel for fires nearby, are at particularly high risk, making them difficult to insure, Powers said.

“Many insurers have revised their brush fire underwriting guidelines, utilizing various fire-mapping vendors,” Powers said in an email. “Fire mapping can vary greatly among these vendors; some of these ‘brush zones’ are more widespread than ever.”

Powers also said the types of risk assessed by insurers are becoming specific to each individual property, its location and its condition.

Building material choices such as wooden roofs or siding have recently been listed as reasons for non-renewals, along with maintenance issues such as chipped paint, curling shingles, debris near the home, trees overhanging the roof and lack of defensible space, she said.

The most pressing issue for most homeowners, though, is cost, and when insurance options dry up, homeowners like Caserio often end up with the “last resort carrier,” the California FAIR Plan, Powers said.

Once on the FAIR Plan, it’s difficult to get out, Caserio said. As the insurer of last resort, that means policyholders have otherwise exhausted all other options.

“(The FAIR Plan claims) to be a temporary option until you can find another carrier, but in this day and age, it’d be a cold day in hell before many insurers write policies again, at least in high-risk areas,” Caserio said.