California law mandates access to police discipline records. That law is weak in Sacramento

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Nia Love is still waiting to learn the name of the officer who shot her in the eye with a rubber bullet, and whether that officer faced discipline for that action.

“Honestly I think it’s disrespectful to me and anybody else that has sustained these injuries, any kind of injury from the police,” said Love, 33, of Natomas.

She is now blind in one eye.

Love is Black and a mother of two. She recalls the events of May 29, 2020, that left her at risk of losing her eye. Love, joined protests following the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd. She joined a group that gathered in front of the South Sacramento police station to demonstrate against police brutality.

She was standing among the peaceful protesters, chanting “Hands up, don’t shoot” when a civilian truck drove through the crowd, she said. Though she heard no warning from law enforcement that the crowd needed to disperse, she felt apprehension and decided to head home. While walking away, she turned back, trying to spot her brother. That’s when she felt a projectile, fired by a Sacramento police officer, strike her eye socket.

Love is not the only Sacramentan who’s been waiting years for the Sacramento Police Department to release internal affairs documents that would illuminate the investigation, review and, when deemed appropriate, the discipline of officers who have inflicted harm on residents. Senate Bill 1421 required law enforcement agencies in California to release those documents for shootings and other uses of force that caused severe injury. Since the bill’s 2019 passage, city police have yet to release internal affairs records for roughly 50 incidents that have taken place, according to The Sacramento Bee’s review.

The law allows for some police records — if they fall into a specified category of exemption — to be withheld from public view. However, the police must cite the exemption when they decline the request. Though the department faces legal time limits to respond, those deadlines are treated as suggestions.

Over two years ago, The Bee filed a request under the California Public Records Act for internal affairs documents related to the investigation of the incident in which Love was injured and any resulting disciplinary action against the officer who shot Love. The department has neither denied the request, which would require it to cite its reason for doing so, nor provided The Bee with responsive records.

Legal exceptions include incidents undergoing criminal review by the district attorney and certain instances in which criminal charges have been filed. The law also exempts internal affairs documents up to six months for administrative review by the law enforcement agency that used the force.

None of these exemptions would apply to Love’s case because the district attorney’s office does not review use-of-force incidents where no lethal firearm is involved and in which the six month review period has expired.

How does The Sacramento Bee obtain public records and get answers for you? We have a plan

What qualifies as ‘great bodily injury’

Another issue is at play in whether records are released: Has the police department determined that a use-of-force incident caused what the law describes as “great bodily injury”? If it is determined that the injuries fall short of that threshold, the incident is not covered under the new law and the agency is allowed to keep the records secret.

City spokesman Tim Swanson said an unknown number of use-of-force incidents related to the Floyd protests did not meet the requirement of “great bodily injury.”

“... (Sacramento Police Department) at the time of its investigation did not receive sufficient information to establish that use of force by an SPD officer resulted in (great bodily injury),” Swanson said. “The city is currently evaluating the release requirements and how they may correspond to information established by other parties at later dates.”

During the week of demonstrations that included the night when Love was injured, officers fired bean bag guns and rubber bullets into crowds in south Sacramento and the central city. At times they were provoked by protesters throwing rocks and other objects, law enforcement agencies said.

As a result of police projectiles, legal observer Danny Garza suffered a concussion, Thongxy “Tee” Phansopha needed two life-saving brain surgeries, according to lawsuits, Joshua Ruiz’s liver was lacerated and Foucha Coner was temporarily blinded and needed seven stitches.

Attorney David Loy of the First Amendment Coalition said the police department is using too narrow a legal definition of “great bodily injury” in choosing to withhold all records related to those incidents.

“’Great bodily injury,’ in our view is any significant or substantial injury and there is a body of case law out there that talks about the kinds of injuries that qualify,” Loy said. “If someone requires surgery, I think there’s no question that’s substantial.”

Love said hearing that Floyd protesters’ injuries were not seen as severe enough to warrant transparency was hurtful.

“We have to go through these surgeries, have to live through these life altering injuries,” Love said. “To not be considered great bodily harm, I think, is a slap in the face.”

How Sacramento police compare to other departments

The city of Sacramento routinely provides disciplinary letters for other employees, including firefighters, in response to public records requests from The Bee. Sometimes the letters are dated just weeks prior to being released.

Swanson said part of the reason the city’s police department has not released more records is due to staffing in the department.

“Public safety is of the utmost importance to the City of Sacramento and the Sacramento Police Department, and we are committed to transparency as well as public accountability in how we serve our residents,” Swanson said in a statement.

He added that the change in state law concerning the release of police records has “significantly increased” both the amount of information the city can release and the workload related to processing the backlog of records. He said the city has been trying to hire more staff to take on this work.

The department has an all-time-high budget of $228 million in the current fiscal year, but still does not have as many employees as it did before the Great Recession.

The county Sheriff’s Office has been slightly more transparent than the city’s police department about the Floyd protest injuries.

As a result of a public records request from The Bee, the Sheriff’s Office last month released the name of the deputy, William Hertoghe, who shot a projectile at the face of Dayshawn McHolder, 18, breaking his jaw. The office, however, did not release whether Hertoghe was disciplined after an internal affairs investigation. He’s still a deputy and did not respond to an email seeking comment.

Still, the Sheriff’s Office continues to withhold internal affairs documents for roughly 55 use-of-force incidents from Jan. 1, 2019, to present. Unlike the Sacramento Police Department incidents, all of those incidents were reviewed by the Sheriff’s Office internal affairs unit, which produced documents, spokesman Sgt. Amar Gandhi said.

The issue continues to erode trust between law enforcement and Sacramento’s Black communities, said Tanya Faison, founder of Black Lives Matter Sacramento.

“The Sacramento Sheriff and Sacramento Police not complying with the law is not only contradictory to their occupation as law enforcement agencies, but it is also very telling that all this talk they give about wanting to be transparent and build bridges with community is just talk,” Faison said. “Since SB 1421 was implemented they have fought hard to not have to be in compliance ... the legislation is very cut and dried. Clearly they are hiding the fact that they are not giving repercussions when their officers violate policies.”

What happens when use-of-force is deemed justified?

Every time The Bee submits a records request to the city’s police department or the county’s Sheriff’s Office for records that fall under SB 1421, the agencies refer the reporter to their transparency web pages. Even though the web pages include many audio and video files, as well as transcripts, photos and police reports, they often lack final disciplinary records from the internal affairs divisions.

The released records, sometimes hundreds of pages, typically include just one sentence that says an official in the law enforcement agency, or its use of force review board, has looked into the incident and found the officer or deputy acted within the policy. If it goes to internal affairs for a more thorough review the agencies typically fail to release those records.

Loy said that this is a misreading of the statute.

While the law allows agencies to withhold records about sex assault, discrimination and dishonesty unless the allegation is sustained, it says they need to release all documents regarding shootings and great bodily injuries, regardless of whether an officer is found to have acted within the policy or not.

“If it relates to shooting at a person or a use of force causing great bodily injury, my view of the statute is those records have to all be disclosed whether there was any disciplinary action, or there are any appeals pending,” Loy said. “They’ve got 180 days to hold on to it but after that they’ve got to release it.”

Gandhi, spokesman for the sheriff, said his office is in compliance with the law.

“We will continue to comply with the law and abide by rulings from the court on the matter, not on the opinions of self-professed experts,” Gandhi said, referring to Loy.

In response to letters from The Bee’s attorney, both agencies have released records of several new cases in recent weeks. That includes an internal affairs document stating one deputy was fired for a sexual relationship with a woman he met on a 911 call. But the public is still in the dark on whether officers were held accountable in dozens of other incidents.

Older records not released

Although the law is retroactive to include incidents prior to 2019, Sacramento law enforcement agencies have not released disciplinary records for incidents that happened earlier than the 2020 protests.

The police department has yet to release disciplinary documents related to Anthony Figueroa, the officer who in 2017 threw Nandi Cain, who is Black, on the ground and punched him repeatedly for jaywalking, causing a concussion and broken nose. As part of a $555,000 settlement, then-Police Chief Daniel Hahn took Figueroa off patrol in Del Paso Heights, where the incident occurred, until at least 2020 and ordered he take implicit bias training.

The Bee learned of this discipline through paperwork from a civil lawsuit settlement, rather than from the department’s response to a reporter’s public records request for those disciplinary documents. Many residents injured by police officers cannot afford to file lawsuits.

Whether Figueroa was disciplined further is unclear. Figueroa is still an officer for the department, and was seen on video working downtown during the Floyd protests. The Sheriff’s Office has not released whether deputies who allegedly assaulted Cain once he got to the jail, causing the concussion, were disciplined.

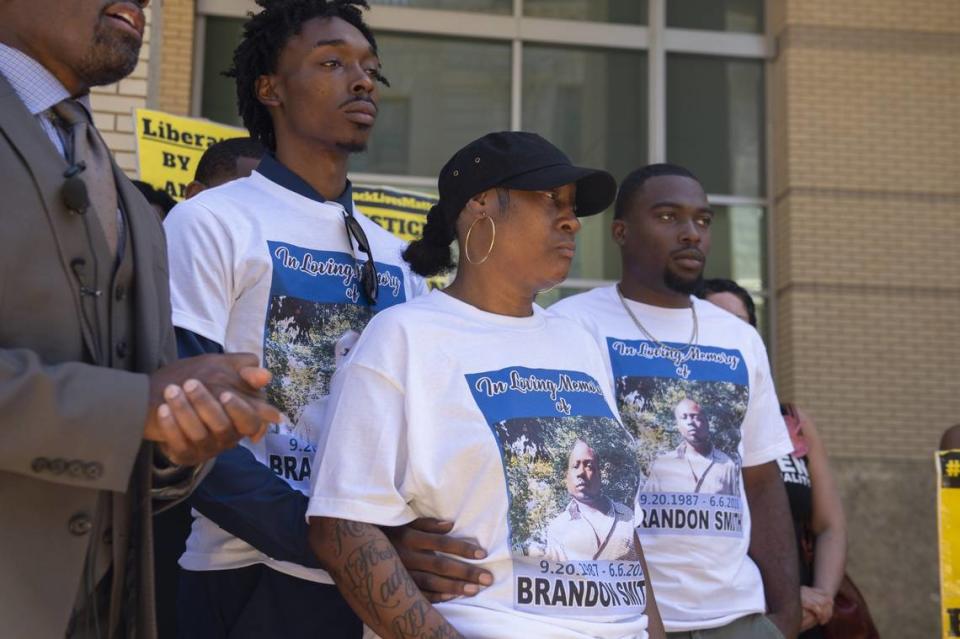

Similarly, the department has not released whether Officer Marcus Smith was disciplined for the June 2018 incident in which Brandon Smith died while being transported in a police vehicle. Smith is still an officer for the department.

The city has not released records that show it has fired an officer for shooting or causing injury since 2017, when it fired John Tennis, one of the officers who fatally shot Joseph Mann after trying to run him over with a squad car in 2016.

Oftentimes, when officers are disciplined, they appeal go to arbitration, with involvement of the police officer union.

It’s possible that process has led to officers being fired and reinstated in recent years.

“In some cases, it is possible that officers retired or resigned prior to discipline being imposed or a letter of intent to terminate was signed but the officer was later reinstated through the arbitration process,” Swanson said.

But if that’s true, Loy said the city should still release the records spelling out what happened, including the original disciplinary record.

Lack of transparency erodes trust

While Love has waited for answers about who shot her in the eye and what repercussions they met, she still deals with her own repercussions from that event.

She needed to have two emergency surgeries to prevent losing her eye, she said.

Over three years later, she still gets frequent headaches, and eye pain, sometimes so bad she is unable to get out of bed for a whole day, she said. Her daughters, 9 and 11, sometimes crawl into bed and try to comfort her.

The lag between events that spur investigations into police misconduct and the public availability of the findings also occurs in police departments across the state, Loy said.

“California is one of the worst states in the country on police transparency,” Loy said. “It’s a little bit better after SB 1421 and 16. But if it’s still not a completely black hole it’s a pretty dark hole ... There’s all kinds of ways the system can still be gamed to promote secrecy in law enforcement. It’s a totally different standard than other public employees.”