California legalized weed, then businesses started suffering. How federal rescheduling would help

Reality Check is a Sacramento Bee series holding officials and organizations accountable and shining a light on their decisions. Have a tip? Email realitycheck@sacbee.com.

The Biden administration’s rescheduling of marijuana could have a big financial impact on California pot businesses.

While dropping weed from a Schedule I to a Schedule III drug would not make it federally legal, it would allow certain tax deductions for legal businesses struggling with the burden of hefty California taxes.

Federal code 280E bars dispensaries selling Schedule I and Schedule II substances from seeking tax breaks for basic operating costs — payroll, utilities, rent, office supplies and more needs — that other businesses can.

If weed is Schedule III, putting it among less-heavily regulated controlled substances like ketamine and anabolic steroids, 280E no longer applies.

The change is desperately needed, said Dale Gieringer, the director of California NORML, which advocates for marijuana reform.

“The legal industry here really needs a shot in the arm,” Gieringer said in an interview, “it’s been really tough times.”

On Tuesday, the U.S. Justice Department, which oversees the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, said that the attorney general had circulated a proposal to reclassify marijuana.

The proposal must be reviewed by another federal office, the Office of Management and Budget, undergo a period of public comment and then review by an administrative judge before the agency overseeing drug regulation could publish the final rule.

The timing is unclear, but the federal process can be lengthy.

California’s excise sales taxes, which can exceed 15%, went into effect in 2018 after the state legalized recreational pot through a 2016 voter-approved ballot initiative, have ended many licensed businesses, said Cody Stross, CEO of marijuana company Northern Emeralds in Humboldt County.

Humboldt County is part of the Emerald Triangle, a lush Northern California region where cannabis cultivation is king. It looks a lot different now than it did a decade ago, Stross said in an interview.

“When I got there, it seemed like it was flourishing economically,” Stross said. “A lot of cash with a lot of people making good money and good living. And that quickly changed.”

“As soon as regulation kicked in, it was a pretty stark contrast,” he said, “and people started going out of business.”

Many legal California marijuana businesses haven’t renewed their cultivation licenses, haven’t paid taxes or closed their doors since the taxes went into effect, said Stross, who also serves on the board of the National Cannabis Industry Association. It’s easier to sell on the illicit market, further squeezing legal dispensaries.

Some relief would come if weed is no longer a Schedule I drug, the most tightly regulated group of controlled substances that includes heroin, LSD and MDMA. Dispensers of Schedule I drugs cannot claim federal tax deductions.

How much do legal California cannabis companies pay in taxes?

In fiscal year 2023, legal cannabis dispensaries provided almost $1.1 billion in state tax revenue, according to the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration. This includes merchandise and other sales unrelated to pot itself, such as pipes, rolling paper and clothes.

California’s licensed retailers reported $4.4 billion in taxable weed sales in 2023.

California has a 15% excise tax on weed sales, which is paid by consumers and remitted by retailers.

On top of that, local governments can levy an excise tax on marijuana companies, per the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center in Washington, D.C. Some local governments tax a weed business on the square footage of their operations and others have gross receipts taxes on the cultivator, distributor and retailer.

Depending on the area, some weed dispensaries may be subjected to taxes up to 40%.

The state repealed a weight-based tax on pot in 2022.

In the face of incorporating high taxes into their sales price, illegal sellers don’t have much incentive to be licensed. Most weed sold in California is from the illicit market.

Reclassifying marijuana as Schedule III could give legal cannabis companies an edge over illicit ones, Karen O’Keefe, director of state policies at the Mairjuana Policy Project, told reporters Thursday.

That gives licensed California cannabis businesses hope.

“Hang on, guys, the light is coming,” Stross said. “If this rescheduling happens, we’re going to be in a completely different world.”

Why is marijuana en route to being rescheduled?

Most changes would be felt outside of California, which is one of 24 states where weed is legal for recreational use and one of 38 where it is legal for medical use, experts said.

Marijuana is and still would be federally illegal after a rescheduling. Schedule I drugs are those considered to have no accepted medical use and have high abuse potential. Schedule III drugs allow for some medical uses; illicit sellers would still be subject to federal criminal penalties.

The federal government rarely charges cannabis users and sellers whose actions are legal under state laws.

President Joe Biden kickstarted the process last year when he asked the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services and Justice to review marijuana’s classification.

After reports and the Department of Justice confirmed the move toward rescheduling, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer stressed in a press conference Wednesday the need to end the federal prohibition on cannabis and pushed again for long-fought-for legislation to ensure state-legal pot businesses have access to bank deposit accounts, insurance and other financial services.

What else would rescheduling marijuana do?

Schedule III drugs are easier to study, meaning that eventually research might be conducted more easily on marijuana’s properties.

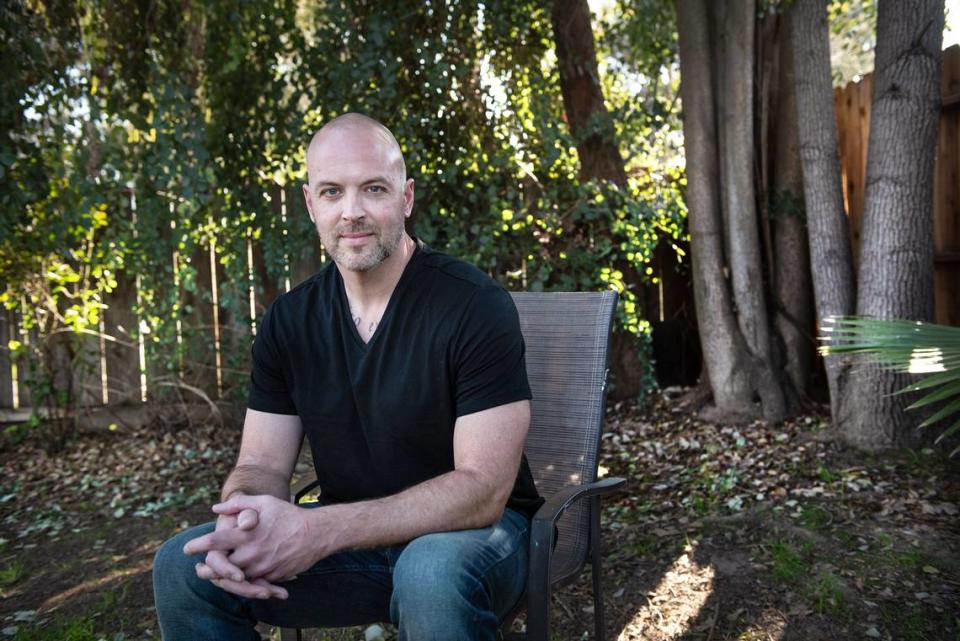

There would eventually be some criminal justice relief, said Luke Scarmazzo, the last known California person who was held in federal prison on cannabis charges. Scarmazzo was released last year after serving more than 14 years of his 22-year sentence.

People facing cannabis offenses could be able to use a medical necessity defense in federal court. Mandatory minimums, the standards that guide judges during sentencing, would be lower, he said.

While it’s good Biden has gotten behind cannabis reform, Scarmazzo said in an interview, more needs to be done: namely, release and expunge the records of people held in federal prisons on nonviolent weed charges.

“We need to continue with cannabis reform and we need to continue in a way that is meaningful,” he said. “Schedule III does not release anyone from prison.”

Scarmazzo and his business partner were arrested and sentenced to federal prison for operating a medical marijuana nonprofit in 2006, even though medical weed was legalized in California through a 1996 voter-approved ballot measure. He wrote a book in prison about his story that published this year and launched a social justice collective to help people incarcerated on cannabis charges with his business partner, Ricardo Montes.

Scarmazzo called the expected rescheduling of marijuana “incremental progress.”

Scarmazzo, Stross and Gieringer said reclassification is a hopeful sign that marijuana could eventually be federally legal. But it took a long time to move toward downgrading cannabis from Schedule I at all.

“I think this was a tremendous realization that should have happened 50 years ago,” Gieringer said. “But that’s why it’s a welcome development.”

The Sacramento Bee’s Andrew Sheeler contributed to this story.