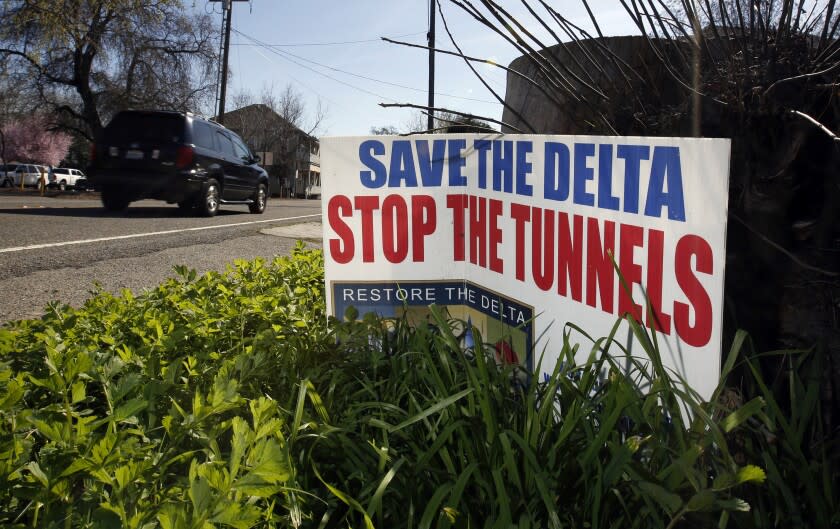

California officially shrinks delta water diversion plan from two tunnels to one

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Gov. Gavin Newsom said in 2019 he would downsize the state's plan for tunneling around the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta to deliver water more easily to Southern California.

On Wednesday, he put some detail into that vague idea — 3,000 pages' worth — unveiling plans for a single gigantic tunnel aimed at making water exports more reliable but with significant costs to the delta farm economy and possibly its fragile ecosystem.

As a historic drought intensifies its grip, and sea-level rises threaten to make the delta more salty, water managers in California's most populated urban areas are growing increasingly concerned about the existing system for pumping supplies through the delta — not only a hub for conveying water but also an estuary that is home to rare species, some on the brink of extinction.

The proposed tunnel — which is a trimmed-down version of tunnel scenarios proposed by the administrations of Govs. Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jerry Brown — would grab excess water delivered by big storms and divert some of those Sacramento River flows to thirsty cities in the south. All along, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California has been a major driver of this replumbing.

"Climate change continues to threaten every water source across the West," said Adel Hagekhalil, the Metropolitan Water District's general manager. "We have a responsibility to adapt to this change by capturing and storing excess water to protect our communities and the environment and to provide the ability to beneficially use that stored water when conditions are dry."

But the draft environmental impact report said the project — a modern-day version of the Peripheral Canal — would also cause "unavoidable" impacts to delta farms, according to the document released Wednesday. It is also unclear how much water would be diverted during different years and flow conditions, which environmentalists fear could harm imperiled fish such as chinook salmon, steelhead and smelt.

"The status quo in the delta jeopardizes the continued existence of our native fish and wildlife, and for the thousands of fishing jobs and communities that depend on a healthy environment," said Doug Obegi, a senior attorney in the Natural Resources Defense Council's water program. "This proposed system would be even worse for the environment than the degraded status quo."

He said it's also unclear the proposal will be permitted, given that federal and state endangered species laws may forbid changed water diversions from habitat that supports already threatened species. If permitted, he said, it'll be challenged in court.

The state's favored proposal outlines the construction of a tunnel — 36 feet in diameter on the inside — crossing the eastern side of the delta, whereas an earlier version went down the middle. It would capture water from the Sacramento River, just 17 miles south of the state capital, and deliver it to the Bethany Reservoir, northwest of Tracy, where the existing State Water Project pumps are.

If constructed, it would be the state's largest infrastructure venture since the high-speed rail system, a project that has faced numerous delays, cost overruns and litigation — hurdles that could also hobble the water tunnels. It would also create thousands of jobs — one reason the state's powerful labor unions have backed versions of it for decades, along with numerous governors.

Cost estimates are running around $16 billion — $3 billion less than the previous iteration, a double-tunnel system proposed in 2018, during Brown's administration.

Large water districts, including the Metropolitan Water District and the Santa Clara Valley Water District in San Jose, have been funding the planning of the tunnel system for years. They are joined by 14 other water agencies that receive water from the State Water Project.

Between 2021 and 2024, that group of water agencies, known as the Delta Conveyance Design and Construction Authority, planned to spend about $360 million on the effort. The Metropolitan Water District is footing about 44% — roughly $160 million.

The single tunnel project is smaller than iterations proposed during the Brown and Schwarzenegger administrations. This new one has a maximum capacity of 6,000 cubic feet per second, whereas Brown's plan called for a capacity 50% higher. Schwarzenegger's plan was even bigger — 15,000 cubic feet per second.

Though huge, all these projects would shuttle significantly less water than one proposed in the 1980s: the Peripheral Canal, defeated by voters, which would have had a maximum capacity of 22,000 cubic feet per second.

Although the proposed tube would be smaller, it could actually provide almost as much water as some of the earlier versions, said Greg Gartrell, an adjunct fellow of the Public Policy Institute of California and an independent consulting engineer.

"This is the problem they’ve had since the beginning," he said. "Bigger doesn’t get you a whole lot more water."

Deliveries of water through the delta have long been constrained by species considerations, and that would not change under this plan. What will change is water quality.

As climate change intensifies, studies show that salt water will intrude farther up the Sacramento-San Joaquin estuary, further threatening the purity of water taken by public utilities in Contra Costa County and Southern California. It is also expected to imperil the supplies of federal water contractors, who have declined to help finance the tunnel project, despite the risks they face.

Obegi, of the Natural Resources Defense Council, said the new plan show makes clear how Newsom and his California Department of Water Resources officials want to proceed. Throughout the process, he said, the administration hasn't fully explored other options, such as conservation and putting a higher price on environmental benefits.

"The fact that they are not even analyzing any alternatives including more protective operating rules and leaving more water for the environment is really troubling," he said.

Other analysts say there is room for California to take advantage of big — and irregular — deluges.

Jeffrey Mount, a senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California, said that over the last 12 years, "we've had three very wet years. And in those years, the vast majority of that water flowed through the delta and into San Francisco Bay."

"Even if you maximized the ability to take some of that water ... it wouldn’t have had much of an effect" on the environment, he said. "There’d still be fresh water all the way to the Golden Gate."

Those arguments have been made before, and California has yet to fully embrace them. The state has studied various blueprints for rerouting delta water since Gov. Pat Brown — Jerry Brown's father — was governor. Newsom is the latest to offer his own proposal.

Assuming he is reelected, Newsom will leave office at the end of 2026. In the most hopeful scenario, construction on this plan wouldn't begin until two years later — assuming it can receive permits and survive lawsuits.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.