California prisons price gouge necessities, leaving inmates struggling to pay for soap | Opinion

Laura Hernandez is no longer incarcerated, yet hundreds of dollars leave her bank account each year and end up in the coffers of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR).

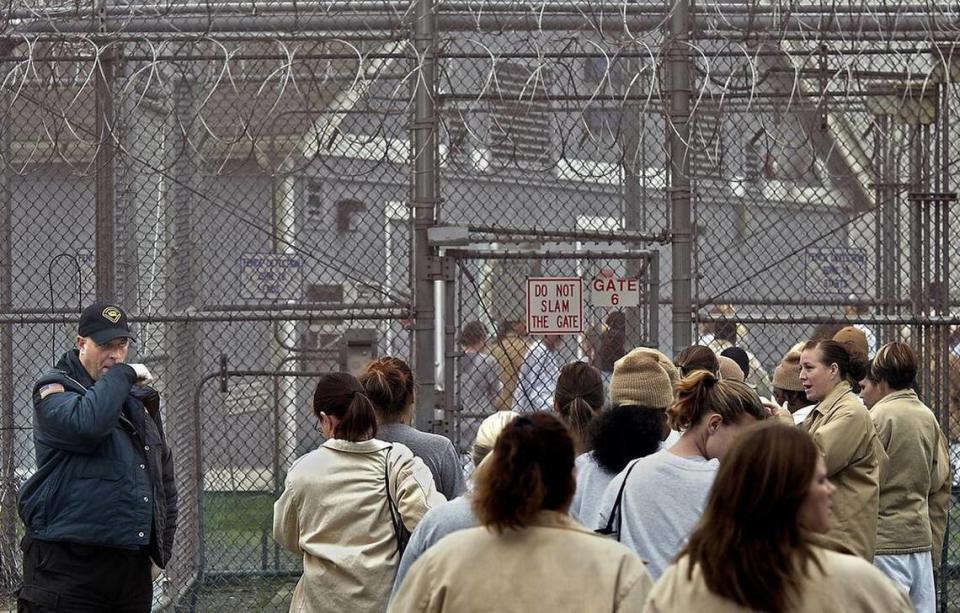

While incarcerated in California from 2007-2018, Hernandez paid exorbitant prices on basic necessities like shampoo, conditioner and bar soap from the prison canteen each month. Even though Hernandez is now a free woman living in Texas, she is still subject to the whims of CDCR’s price-gouging as a person who supports incarcerated loved ones. When Hernandez receives word that one of her incarcerated friends needs something, she mobilizes with groups of formerly incarcerated women to raise funds. Without this sisterhood of support, many of Hernandez’s incarcerated friends would have to go without the bare essentials.

Legislation now on Gov. Gavin Newsom’s desk from Senator Josh Becker (D-Menlo Park) could help women like Hernandez who support incarcerated loved ones, as well as the more than 92,000 people incarcerated in CDCR facilities. In its current amended version, Senate Bill 474 would prohibit CDCR prisons from charging more than a 35% markup above the amount paid to vendors until January 1, 2028. This would dramatically lower prices — a recent audit found that canteen products are marked up an average of 65% of the amount paid to the vendor.

Opinion

Because prisons have a monopoly over the people they incarcerate, they are able to gouge prices far beyond retail prices in order to maximize profit. It’s often impossible for incarcerated people — who earn between 8 and 37 cents an hour — to afford these prices. At California State Prison Solano, toothpaste costs $4.45 (compared to the market rate of $1.38), a markup of over 200% that could require 37% of an incarcerated person’s monthly income.

An eight ounce package of coffee can cost $9, as much as 75% of an incarcerated person’s income. Only in a forced monopoly can these kinds of prices exist. In the free world, a consumer would simply shop elsewhere. With the lowest-paid people in the country being charged the highest prices for basic necessities, the expense often falls to their loved ones.

“Imagine having to stretch $21 (a month) for hygiene,” Hernandez said, citing the health risks and social humiliation of not being able to afford soap or menstrual products. Even when her family sent her money, a portion of the funds went toward restitution fees. And many in prison don’t have anyone on the outside to offer financial support.

April Harris, who is currently incarcerated at California Institute for Women, receives support from her mother, stepfather and three friends, including Hernandez. Yet, for the first five or so years of her incarceration, she didn’t have the same level of financial support and could not afford supplemental food items from the canteen.

Restricting canteen price-gouging wouldn’t just help incarcerated people, but also their families, who “pay both the apparent and hidden costs” of incarceration, according to a 2015 report published by the Ella Baker Center, an SB 474 cosponsor. Decades of “unjust criminal justice policies have created a legacy of collateral impacts that last for generations and are felt most deeply by women, low-income families and communities of color,” the report continued.

Prison-related costs for loved ones can have debilitating ripple effects. A survey of 2,281 women published in 2018 by Essie Justice Group found that 35% of respondents experienced homelessness, eviction or an inability to pay housing costs on time as a result of their loved one’s incarceration.

San Francisco has already succeeded in ending markups in its city jail’s commissaries, a change the city enacted in 2019. On a national level, no other states have yet passed such legislation, though Virginia and Nevada are also fighting for similar legislation.

In addition to Newsom signing SB 474, future legislation could address the prices of items in the catalogs from which incarcerated people and their loved ones can order quarterly packages. Harris also wonders if CDCR could spend the inmate welfare fund differently, perhaps using the funds to include better, name-brand products in the indigent kits.

Hernandez recalls a time when prisons allowed outside packages to be sent in, rather than requiring families to send packages from these approved vendors. As someone who is now sending, rather than just receiving these packages, Hernandez thinks that allowing outside packages would be cheaper and logistically smoother.

“I think it would be a lot easier… for us out here,” Hernandez says. “To be able to help the ones that are in there.”

Rachel Zarrow is a freelance writer based in San Francisco and a volunteer with Empowerment Avenue. Christopher Blackwell is an incarcerated writer in Washington State and a co-founder of the nonprofit Look 2 Justice.