California rain, flooding might bring back long-dead Tulare Lake. Let’s hope not | Opinion

I consider myself an environmentalist, and also a history buff.

Despite both of those things, I’d rather not see Central California’s most renowned phantom body of water — Tulare Lake — lurch back to life.

In writing this, I realize it might already be too late. Water from swollen Sierra rivers and creeks is already making its way toward the historic lake bed in Kings County. And this is probably just the start.

An aerial photograph posted on Twitter by Justin Mendes, a regulatory specialist for the Tulare Lake Basin Water Storage District, showed a swath of agriculture fields in the former lake bottom covered in water. There are reports of flooded orchards almost as far south as Highway 46 in Kern County. And of course Lake Kaweah and Lake Success continue to pour over their respective spillways, forcing evacuations of downstream communities and contributing to flooded sections of Highway 99.

Unless captured and diverted, all that water is headed for what used to be Tulare Lake. For the simple reason that there’s nowhere else for it to go.

Opinion

“I wouldn’t be surprised at all” if Tulare Lake re-emerges, local historian Randy McFarland said. “Nobody wants to put water down there, but it may become inevitable.”

When I worked in the Tulare Lake Bottom, I often joked about creating the Tulare Lake Yacht Club.

Might be time to register a trademark and print some shirts. #cawater pic.twitter.com/sXLbEW0aqd— Justin Mendes (@MrNFKGSA) March 16, 2023

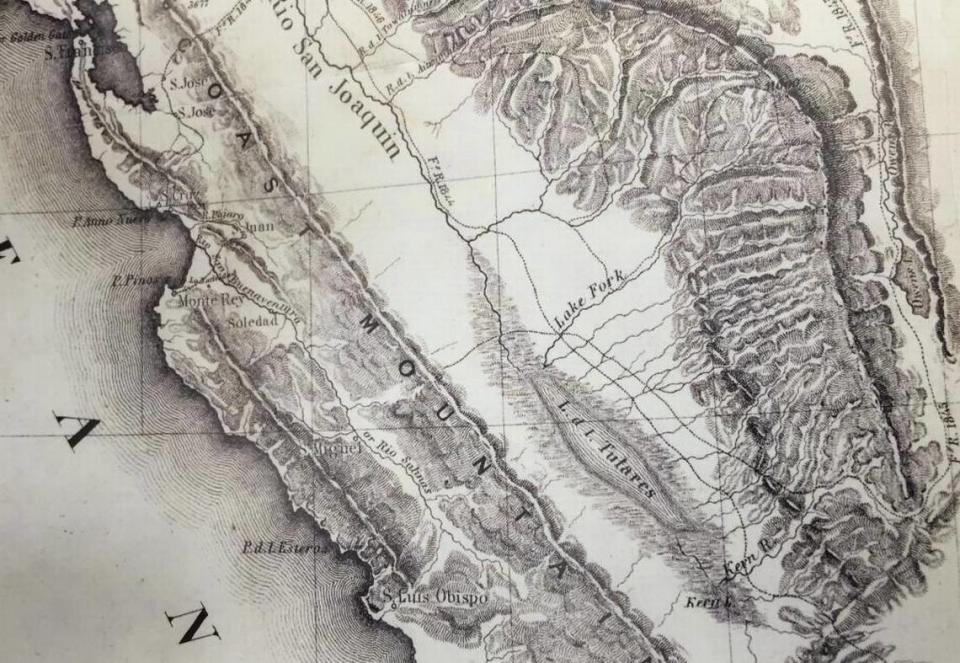

Largest lake west of the Mississippi River

For those unfamiliar with Tulare Lake, until the late 1800s it was the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River. No, really. In wet years it covered 960 square miles (Lake Tahoe is 191 square miles by comparison) and sustained both a thriving indigenous population (the Yokuts people) and diverse wildlife: vast flocks of migratory birds, an abundance of fish as well as western pond turtles served as terrapin soup to diners in San Francisco.

Had the cities of Corcoran and Stratford existed during Tulare Lake’s heyday, they would have been submerged beneath 25 feet of water sent down the western slope of the Sierra Nevada mountains via four major rivers (Kings, Kaweah, Tule and Kern) and several smaller tributaries. There was no outlet, except in extremely wet years when the lake would spill north into the San Joaquin River drainage.

Starting in the 1860s, irrigation districts began constructing levees, canals and dams to divert water from Tulare Lake for agriculture. By 1900, the lake essentially disappeared, but would reform on occasion. The 1954 completion of Pine Flat Dam, which subdued the mighty Kings River, proved the final nail.

Since then, Tulare Lake has periodically reappeared when the amount of water overwhelmed the ability of landowners to prevent it from flooding their fields. It happened in 1983 when a massive snow year led to a prolonged spring runoff, and again in 1997 following severe winter storms.

This year both of those scenarios are in play. California is having an epic winter, resulting in one of the largest Sierra snowpacks in recorded history. Most of that snow has yet to melt.

The Kings River has an average annual flow of roughly 1.8 million acre-feet of water — larger than the combined flows of the Kern, Kaweah and Tule. This year, the forecast projects 3.1 million acre-feet in the watershed between April and July, according to Kings River Water Association watermaster Steve Haugen. Which is roughly the same amount as in 1983.

“There’s 3 million acre-feet in four months, and you’ve got a 1 million acre-foot reservoir (when empty),” Haugen said in reference to Pine Flat Lake, which was at 77% capacity Friday. “That water’s got to go someplace.”

Lake’s reappearance hinges on multiple factors

Despite the daunting “napkin math,” Haugen did not want to predict the reappearance of Tulare Lake. Rather, he said it depends on multiple factors, including the rate of snow melt (does it happen gradually or suddenly?) as well as how many more storms impact Central California.

Haugen also mentioned water recharge, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act and changes to crop patterns as factors that could prevent flooding. Upstream pumps have also been installed on the Kaweah near Visalia and the Tule near Porterville to pump water out of those rivers and into the Friant-Kern Canal.

“There’s a lot that’s been done since 1982-83 that help us in this situation,” Haugen said. “A lot of water still needs to get moved. But we also have more facilities and capabilities than there were back then.”

It should be noted that the initial surge of excess Kings River water (up to 4,750 cubic feet per second) winds up in the San Joaquin River via the James Bypass and Mendota Pool, where 600,000 acre-feet are planned for groundwater recharge. Reportedly, this is due to a decades-old agreement between the federal government and J.G. Boswell, the late Kings County cotton magnate whose company continues to farm in the Tulare Lake Basin.

Regular readers know I have a deep appreciation for nature and no great affection for giant corporate agribusiness. So why am I not cheerleading on behalf of a certain extinct body of water?

There’s a simple answer: Because when Tulare Lake came back in 1983, 85,000 acres of farmland flooded. It took two years for things to dry out so that cotton could once again be planted.

That’s a lot of economic devastation — not just to ag barons but to farm laborers and small business owners in cities like Corcoran who are dependent on the ag economy.

Furthermore, a blog post by the Public Policy Institute of California speculated that land subsidence in the old lake bed (caused by groundwater pumping) could lead to more extensive flooding than previously seen and reduce the capacity of canals to move water.

Those calamities I wouldn’t wish on anyone. Even to witness a natural and historical event as momentous as the re-emergence of Tulare Lake.