It's called the home of the Braves, but H.L. Bourgeois might have disliked that

At H.L. Bourgeois High in Gray, Native American references — or what some see as corruptions of that heritage — are ubiquitous.

The school, along La. 24, has an official street address of 1 Reservation Court, and sports teams called the Braves. Its logo and branding feature stylized images of Native American warriors. At games, the Marching Sensation from the Braves Reservation, the school’s band, might perform the HLB fight song, a version of the jazz standard “Cherokee,” as the Raindancers dance team entertains fans. During commencement in May, graduates did the tomahawk chop and chanted along to drumming from the band, something not uncommon at school events.

Only about 4% of the school’s 1,300-plus students claim Native American ancestry and heritage. And the school’s references, which rankle some local Native American leaders, are made more difficult to endure because of the man the school is named for.

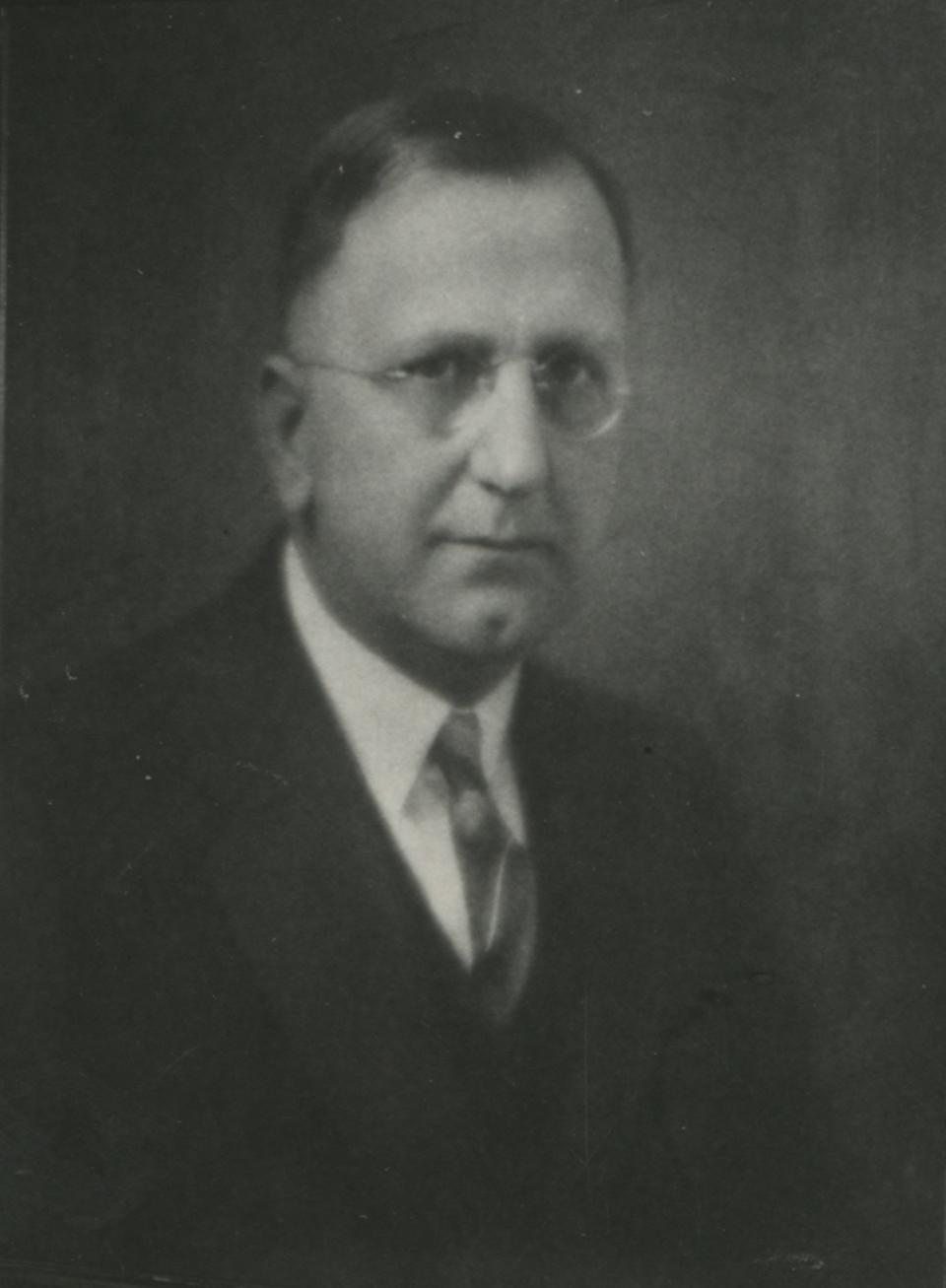

Henry L. Bourgeois, the longtime educator after whom the school is named, had a bigoted history concerning Native American students, parents and the local indigenous community altogether.

A St. James Parish native, Bourgeois was appointed Terrebonne Parish’s public schools superintendent in 1911 to fill another’s unexpired term and was continuously reappointed through 1955.

“The people of Terrebonne Parish recognize the fact that their children are under the supervision of a very able man and that they, themselves, are under an obligation to him for the interest he constantly displays in his work,” one biographical sketch published during his lifetime states of the lifelong Democrat, crediting him with educational improvements.

Bourgeois' entire tenure saw him presiding over a thoroughly segregated school system in an era where Jim Crow laws were the norm across the South. He has an especially clear record of denying Native students educations, maintaining that they be classified as “colored,” and refusing to budge on the issue.

'Over his dead body'

“He saw to it that Indian students would get an education here over his dead body,” said Lora Ann Chaisson, principal chief of the United Houma Nation, a Native American tribe with 17,000 members in Terrebonne, Lafourche and surrounding parishes. “He didn’t hide it. He said that we didn’t exist, that we were a thing of the past. Having a school named for him is a mockery.”

Earlier: Pointe-aux-Chenes community reflects on importance of elementary school as closure nears

Albert Naquin, chief of the smaller Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, is well aware of Bourgeois’ reputation among his people.”

“The name is offensive. H.L. Bourgeois was a racist, I believe,” Naquin said. “He made fun of the Indians.”

Much of Bourgeois’ reputation concerning his feelings toward Native people is committed to print in a 1938 master’s thesis called “Four Decades of Education in Terrebonne Parish.”

“They call themselves Indians and claim a social status comparable to that of the white man,” Bourgeois wrote of Houma tribe members. “But, as a matter of fact, they are not Indians. They are the descendants of that union of the Indian and the free gens de couleur (Black people) of many generations back, with large infusions of white blood. They are pariahs. They disdain contact with the negroes, and they find the doors of the whites closed against them. Consequently, they have thrust themselves into an imaginary racial zone standing midway between the whites and the blacks.”

To Bourgeois, the only place for Terrebonne children whose families claimed being Native American was in Black schools.

Native people claimed they were not Black and that their children therefore should not be relegated to Black schools, whose operations were known to be inferior under the so-called “separate but equal” system that prevailed throughout the South. Neither were they white. But the school system — largely under Bourgeois’ direction — would not consider adding Native American schools to its segregated system until at least the 1940s, according to school district records, and even then, not in any widespread manner.

Remembering: Former students share memories of Houma's Daigleville School for Native Americans during era of racial segregation

Several scholarly accounts of Terrebonne school histories state that Bourgeois was not shy in sharing his disdain for the parish’s native people publicly, doing so on more than one occasion at School Board meetings.

Perhaps most insulting to many of today’s Native leaders was his use — at School Board meetings and also in his thesis, of the phrase “so-called Indians” in referring to their people.

The school’s nicknames draw a less-unified response from Native leaders than opinions of Bourgeois himself.

A campus called the 'Reservation'

Both Naquin and another of Terrebonne’s Native elders, former Houma Nation chief Kirby Verret, find some irony in the fact that a school named for a man who was no friend of Natives is now called the “Reservation” and its teams the “Braves.”

But Chief Chaisson finds little humor in the situation.

Well-networked with national organizations fighting for the rights of Native Americans, the chief had taken part in protests against continued use of names like “Indians” and “Redskins” as names of sports teams. And then one day a thought struck her like a lightning bolt.

“There I was protesting the Washington Redskins name,” she said. “But here are the Braves and the Reservation, right in my own backyard, and I am doing nothing.”

Chaisson has been making her thoughts on the subject locally regarding H.L. Bourgeois and had a meeting with Terrebonne schools chief Bubba Orgeron. She said he is reviewing a study on the harm such monikers pose for children.

She also said the “Braves” related customs make it easy for students to be intolerant of Native Americans. That intolerance is no secret to Jessica Laughlin, a New Orleans attorney who works closely with Chaisson and graduated HLB in 2002.

She said that in her high school years it was not unusual for staff members to instruct students how to spell the school by telling them “Bourg” like the town for the first part, and then for E-O-I-S to say “every other Indian stinks.”

“It was kind of common knowledge and I do remember someone saying it, and it was accepted,” said Laughlin, a Native American from Dulac. “It is offensive.”

Two decades later, another HLB graduate said, the offensive mnemonic is ubiquitous.

Bethany Leonard, a Nicholls State University student who now interns at the United Houma Nation’s headquarters, is not a Native person. But she recollects that when she attended HLB – she graduated two years ago – the phrase or derivations of it were in use by students and faculty as a way of knowing how to spell the school’s name.

She has heard “stinks,” as Laughlin recalled, but also the word “sucks” instead.

“At the time I did not know there was something wrong with it,” Leonard said. “I do think that the mascots promote this a little bit. It dehumanizes the person. You can do harm to a person who is Native American.”

Like Chaisson, Leonard would like to see a change in name for the school, and a change in its culture.

Chaisson said she plans to make her thoughts on the matter more publicly known and welcomes the idea of a name change.

'They are passionate'

But with strong resistance to name changes for schools offensive to at least some Black people — a little less than 20% of Terrebonne’s population — questions naturally arise as to how much consideration a group comprising roughly 6% of the parish population might receive.

Among School Board representatives unlikely to show sympathy for a name change at HLB — or the nicknames of its teams — is veteran member Roger Dale DeHart.

He said he has a much greater concern about the declining number of students applying for attendance in the district’s federally funded Indian Education Program.

“The grant is still there, but there are fewer parents of Indian students saying the father or mother is Indian,” DeHart said. “If we can increase the numbers, I will fight for them.”

DeHart noted that generations of HLB alumni have identified with the school’s name and the nicknames associated with it.

“They’re called the Braves, that’s their mascot,” DeHart said. “The students, the faculty, no matter the name of the school, they are passionate and all have made it a better place.”

Next in the series: Ellender Memorial High School in Houma. John Kelly DeSantis is a freelance journalist and a former reporter for the Houma Courier and Thibodaux Daily Comet.

This article originally appeared on The Courier: H.L. Bourgeois' High's namesake showed bigotry toward Native Americans