Revealed: The FA chief who abused boys but was kept out of Sheldon report

Survivors of child sexual abuse in football have called for a new independent investigation after the authorities were accused of “glossing over” the paedophile crimes of a leading administrator with close links to the Football Association.

Ray Barnes was full-time secretary of the Hampshire Football Association between 1976 and 2001 and, during almost 50 years as a referee and then senior official, used his position to prey on young boys, one of whom he abused on the way back from Wembley after getting tickets through the FA for the 1983 Cup final.

He was also leading the Hampshire FA during Bob Higgins’s widespread sexual abuse of young footballers in the county. Barnes killed himself in 2010 shortly after being convicted of five counts of indecent assault against three boys between 1964 and 1983.

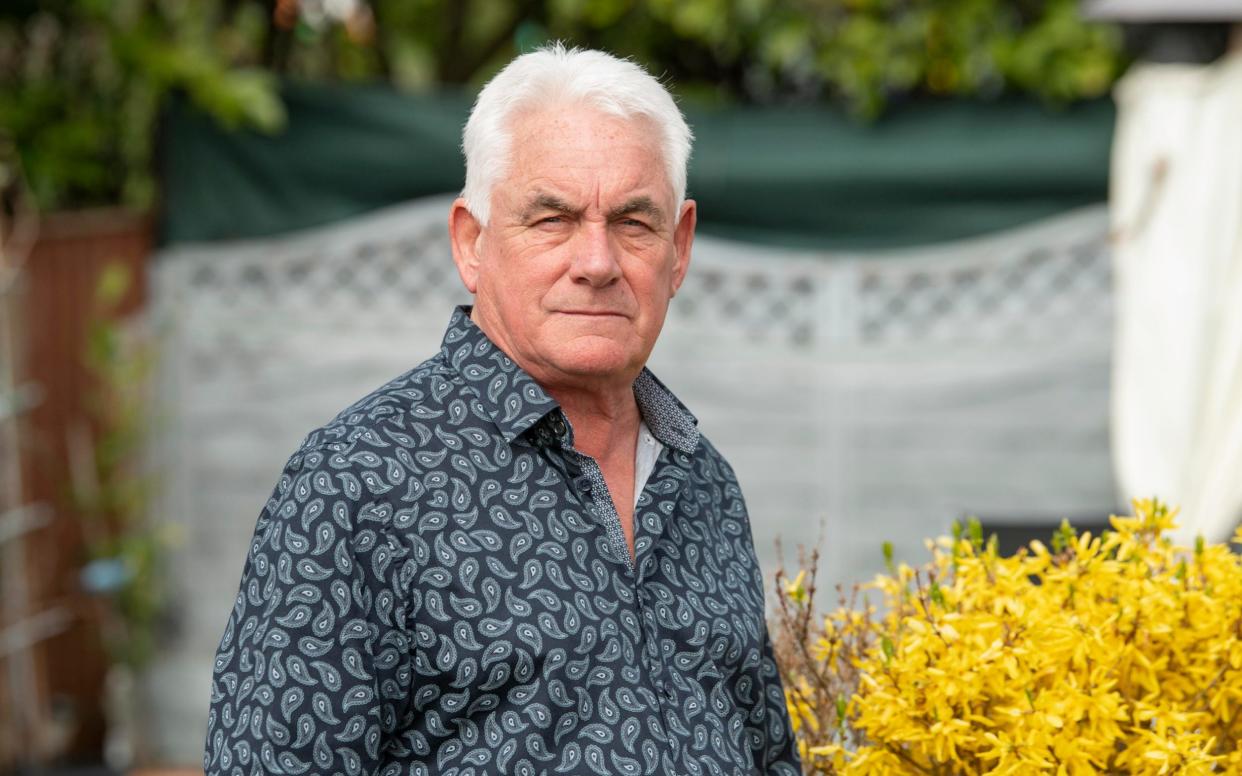

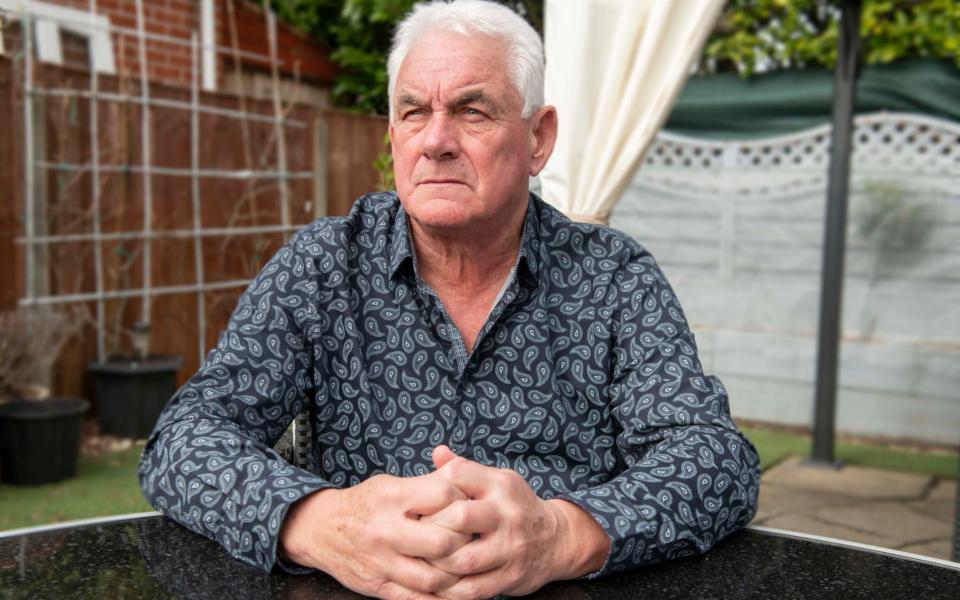

One of the survivors, Geoff Smith, was indecently assaulted by Barnes when he was 11 and is now waiving his right to anonymity for the first time at the age of 68. Smith was not approached as part of the Sheldon Review into child sexual abuse in football and says that there had never been any attempt at a personal apology, support or investigation from the FA or Hampshire FA. “They swept it right under the table,” he said. “We went through just as much as the lads from the professional clubs and we’ve had no apology. I don’t think they want to know.

“How his name was not in the report astounds me. I still believe there are many more who could have been abused by him. It’s very difficult to come forward but is something I thought I had to do.”

The Hampshire FA even commended Barnes’s “outstanding service” in an official history that was published in 2013 — and only taken off the FA website following questions raised by Telegraph Sport’s investigation — and he was not named in the 710-page FA-commissioned Sheldon Review.

Smith was indecently assaulted in the mid-1960s after first meeting Barnes outside a pub where he would serve food and drinks to local children playing football. He was later invited to a Southampton reserve team game by Barnes, who he says wore a blazer with the Hampshire FA badge. The Wessex League, where Barnes became president, even suggested a minute’s silence in his memory following his death aged 74 just over a decade ago.

Another survivor, who he assaulted on their journey home from the 1983 FA Cup final, was given a job by Barnes at the Hampshire FA but then sacked after Barnes made the unfounded claim that he had been stealing.

Barnes was also the Hampshire FA secretary when a parent reportedly spoke with an unnamed senior official about Higgins, the notorious Southampton coach who was jailed in 2019 for 45 counts of indecent assault between 1971 and 1996.

Higgins later also held positions at non-league clubs in Hampshire, including Winchester City and Bashley, and continued running coaching sessions in the area even after numerous accusations had been made.

Dean Radford, who first formally complained about Higgins in February 1989, said that he was staggered that Barnes was not named by Sheldon and that there were not more detailed investigations into the abuse he perpetuated, his influence as an administrator and also his potential links with the Higgins case.

“How can this four-year report, millions of pounds, no stone unturned supposedly, not thoroughly investigate a guy working for one of the FA’s county associations who has been charged and convicted of five counts of indecent assault?” asked Radford.

Dino Nocivelli, a partner in the abuse team at Bolt Burdon Kemp, contrasted the differences between the responses of the FA and Hampshire FA to how clubs have been investigated, conducted their own internal investigations, met with survivors and offered apologies to survivors. “It is just not good enough and results in even more distrust about the whole process,” said Nocivelli. “We now need an external body to look at this. It can’t be the FA again. They have had their chance.”

The Sheldon Review would not comment on its investigation into Barnes but Clive Sheldon QC did meet one of the other survivors and considered the case. He did not name Barnes because he believed that there was a confidentiality obligation to a public body.

The FA released their safeguarding file on Barnes to Sheldon and pointed to the general apology that had been issued to all survivors of child sexual abuse in football.

Hampshire Police would not say how many complaints there had been about Barnes or whether more people had come forward after the full extent of abuse in football had emerged in 2016.

The Hampshire FA had no contemporaneous documentation in relation to Barnes.

Their chief executive Neil Cassar said that they had received no complaints directly “and therefore have not reached out directly to any survivors” but would “supply details on available support” if they came forward.

Smith said that he and the other survivors would have been easily contactable following Barnes’ conviction at Bournemouth Crown Court in 2010.

Radford said that the Barnes survivors had been treated “like they didn’t exist” and was also outraged by how Barnes was praised in the Hampshire FA’s history book.

“It just typifies what the attitude of some people has been,” said Radford. “It’s heartbreaking. Would any business who had an employee for 25 years, who was a convicted paedophile, be paying tribute to them? The whole thing has given me no faith in any sort of establishment.”

Geoff Smith: Why I'm speaking out, 40 years after my abuse by Ray Barnes

More than 40 years had passed but, when Geoff Smith saw a photograph of Ray Barnes beside a newspaper report detailing his arrest, something suddenly changed. And, for the first time, he thought that he would be believed.

Smith was indecently assaulted by Barnes at the age of 11 and the only person he had previously ever felt able to tell was his wife.

“I just pointed at the paper and said, ‘That’s him, there, the man who abused me’. I read it and phoned the journalist. I said, ‘I don’t know what to do but this man abused me as well’. The journalist suggested I report it to the police and they then did a full video interview.”

Smith was in his late fifties by then but every awful detail was still lodged in his mind, right down to the car that Barnes would drive and the clothes he wore.

They had met when Barnes befriended local children who would buy lemonade and crisps from the Bridge Tavern pub next to where they played football. “He worked part-time and he would serve you and start talking,” says Smith. “Looking back, you can see the grooming and how it works.”

Barnes first offered to take Smith in his car to a local airport strip to show him how to drive. He then invited him to The Dell for a Southampton reserve team match, serving up egg and bacon at his home before the game. “I remember he had a blazer with the Hampshire FA badge on when we went to the football — and he had a pass to get in,” says Smith.

The grooming continued for around a year before Barnes told him that he was an artist and suggested that he come into a flat with him. “He was like, ‘I’ll draw you, take your clothes off’ and then came over and started touching me. I went back on the bus that night and felt absolutely numb. There was no one in my family who I could talk to.

“My parents had split up — and my dad was just not the sort you could tell. Ray Barnes would have died that weekend if my dad had known. That’s the way he was. And who would have believed my word against his back then? I avoided him after that. Christ knows what would have happened if it had carried on.”

Both Barnes and Smith still lived in the Southampton area and he would sometimes see his abuser refereeing football matches. Barnes became the assistant secretary of Hampshire FA in 1972 and then the paid secretary between 1976 and 2001. He was also a special constable and a magistrate. He worked with youth offenders and at other local sports clubs, remaining absolutely embedded in football administration until his trial at Bournemouth Crown Court in 2010.

His time leading the Hampshire FA also coincided with when Bob Higgins, one of the most prolific paedophiles in football’s entire child abuse scandal, was also working at local clubs. It all raises obvious questions about how many other victims there might be and Barnes’s role in the failure to stop Higgins from offending.

As well as Smith, a third survivor also came forward after reading the initial complaint against Barnes. He had been given a job by Barnes at the Hampshire FA and was just 16 when he was assaulted on the M3 after Barnes had used his position to get them tickets for the 1983 FA Cup final between Manchester United and Brighton & Hove Albion.

The police, says Smith, were meticulous in verifying the detail of his complaint even if some of the wider reaction provides a telling insight into how so many abusers were able to continue offending. “I was at a reunion with friends and they didn’t know what had happened to me,” he said. “They started talking about Ray Barnes and a few of them were, ‘I’ve known him for years, good lad, they’re having him on’. I said, ‘You haven’t got a clue what you are talking about’ and I just got up and left. People thought that way — they don’t know what really goes on.

“I was put on my own at court. I didn’t see any other witness. It was hard — it’s embarrassing — but, if you don’t tell the truth, you’re never going to get this man convicted. It made me feel so much better to be believed. ”

Barnes was found guilty of five counts of indecent assault on three boys. Don Tait, prosecuting, said that “the genie is now out”. The verdict reverberated through the local community and, within a week, Barnes was found dead. He had been granted bail ahead of sentencing and jumped from the upper level of a multi-storey car park in Southampton city centre.

Some of the reaction inside football was again revealing. A minute’s silence was suggested by the Wessex League for the married father of four, who they called “a stalwart of football”. A local backlash meant that got shelved and Bob Purkiss, the current vice-chair of the Wessex League, has now acknowledged that it was the “wrong thing to do”. In stressing the league’s commitment to safeguarding, he also told Telegraph Sport that lessons had been learnt.

Smith has heard nothing from the FA or Hampshire FA, even since football’s wider child abuse scandal was revealed. He has also heard nothing from the FA-commissioned Sheldon Review which was published last month. He had been ready to share his experiences in the hope that children could be better protected. The apparent lack of curiosity into the entire Barnes case, given both his senior administrative position and proximity to Higgins, has baffled and infuriated survivors.

“The apologies have not been personal whatsoever,” said Smith. “The FA could get all the names of the people who were affected and then send an apology individually. That’s not a hard thing to do. I knew people from the Hampshire FA. I presume they had someone at the trial. Never ever did I hear from them. Ray Barnes used football and sport. You just wonder if someone could have stopped a lot of this.”

Now 68, Smith knows that the experience will never leave him.

“It is something that makes you start doubting yourself,” he says. “Was I wrong to go there? You start thinking, ‘Is it me?’ It messes you up. I was 11. I’ve always felt there is something there. I’ve tried to get on with it as best I can over the years.” Having been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis 26 years ago, he now runs his own charity and has raised more than £1million helping other people with the disease. “Our names were kept quiet at the time of the trial but I don’t mind now,” he says. “It hit me when I saw the other lads on the television in that BBC documentary. I thought ‘fair play to them’. It’s very difficult to come forward. It will never leave us - it happened - but I hope that getting it out there will help others.”