'Calves connect me with life': Veteran finds peace through farming, shares it with others

The newborn black calf hopped as Marvin Frink grabbed its rear leg and checked the "equipment" of the newest addition to Briarwood Cattle Farms.

“It’s a bull calf, baby, a bull!” he hollered to his wife, Tanisha.

“It’s amazing,” he said as the calf watered the pasture.

The baby teamed up with his other new siblings — all black, except one white with tan spots — and they galloped toward the adults, tails up like a CB antenna.

“I struggle with death so much. Newborn calves connect me with life," Frink said.

He leaned on his rattle paddle. It’s a tool devised by cattle innovator Temple Grandin to direct cattle gently, without prodding.

Tanisha asked if Frink needed his cane. He refused, then paused. “That’s a pride moment,” he acknowledged.

Frink had left off his usual cowboy hat that August morning because he had a migraine. And his bad right knee was especially painful because he had kicked through the night, the nightmares.

Black Angus cattle saved Frink’s life. He had three rough deployments in the Middle East, then worked on the civilian side in counterterrorism. He was contemplating suicide when his father sent him to a cattle farm owned by a friend and veteran in Florida. Frink sat with the cattle and felt accepted. He realized what he wanted to do with his life.

It took time, but he bought two pairs of cows and calves, then the acreage on the border of Hoke and Robeson counties in rural North Carolina. Now Frink sometimes spends all day in the pasture, watching from a folding chair while the bugs hum. Sometimes his old military buddies join him.

Bringing hurt people to spend time with healthy cattle is a key part of Briarwood’s mission. Frink works mental health into all he does. He speaks openly about his struggles and going to therapy, to normalize that for others like him who have been told to shut down: men, veterans, Black men, farmers.

Every year, the Frinks convene a Day of Healing on the farm for veterans. This year’s installment included yoga, sound healing and a business talk. He calls it “agri-therapy.”

‘I know my worth’

Black cattlemen are rare. They owned just 2% of the nation's beef cattle farms in 2017, according to the Department of Agriculture. There were 729,046 beef cattle farms in the U.S. in 2017, according to the USDA. 16,934 were owned by Black people.

But “I know who I am, I know my worth, I know my history,” Frink said.

At an otherwise all-white cattlemen’s association meeting, one man came up and sassed Frink about his cowboy hat. Frink could tell from the body language — one of his specialties in the military — that the white dude felt outclassed and defensive.

Frink told him the long history of Black cowboys and their headgear — from the shade hats worn by enslaved African vaqueros, to the kit of the Buffalo Soldiers. A story of Black men working with pride even as they were treated as second-class or worse.

“My history is what you’re wearing on your head,” Frink said.

The man put his own hat over his heart and apologized.

Now they’re friends.

The slaughterhouse bottleneck

Heads down, the cattle snapped stalks of grass on which the dew was rapidly drying.

“Hear that snap? That’s the vegetarian turning into beef,” Frink said.

Briarwood doesn’t sell at farmers markets because Frink didn’t like the data on chest coolers and thawing. Instead, they deliver — to restaurants, to pitmasters, to people. They’ll sell you a whole cow if you want — 440 pounds of meat, costing about $5,200, separated into the cuts your culture favors. They’ll go to Virginia or Georgia. The USDA radius for “local” farm products is 400 miles, he points out.

They can’t keep up with demand — not for the cattle, the pigs they raise on other property or their backyard broilers pecking in the grass.

“People want to know their food now, and they want to know their farmer,” Frink said.

Slaughtering and processing are the biggest bottleneck. It’s at least “18 months now to get one cow processed,” Frink said. “That’s slow to getting you guys food.”

There’s such a shortage of slots in small-scale USDA-inspected slaughterhouses, it’s like putting your name on the day care list the minute the pregnancy test turns pink.

The Frinks planned to open their own slaughterhouse and processing facility to help fill that need — and employ 60 people in a part of North Carolina that needs the jobs. But in August, they scrapped the plan. The equipment cost too much. (The $2 million industrial plumbing bill didn’t help.) Even with a county economic development grant, the loan would have cost $200,000 a month, bleeding Briarwood and its cattle dry.

Instead, the Frinks are retrofitting a shipping container into a small chicken-processing plant. They put out a request for secondhand equipment.

Farm finances aren’t easy. Would Frink be able to sit with his cattle all day if he didn’t have a disabled veteran pension? “It’d be a struggle,” he said. “Farming is a struggle.… It’s a vision no one sees.”

Focusing on healing

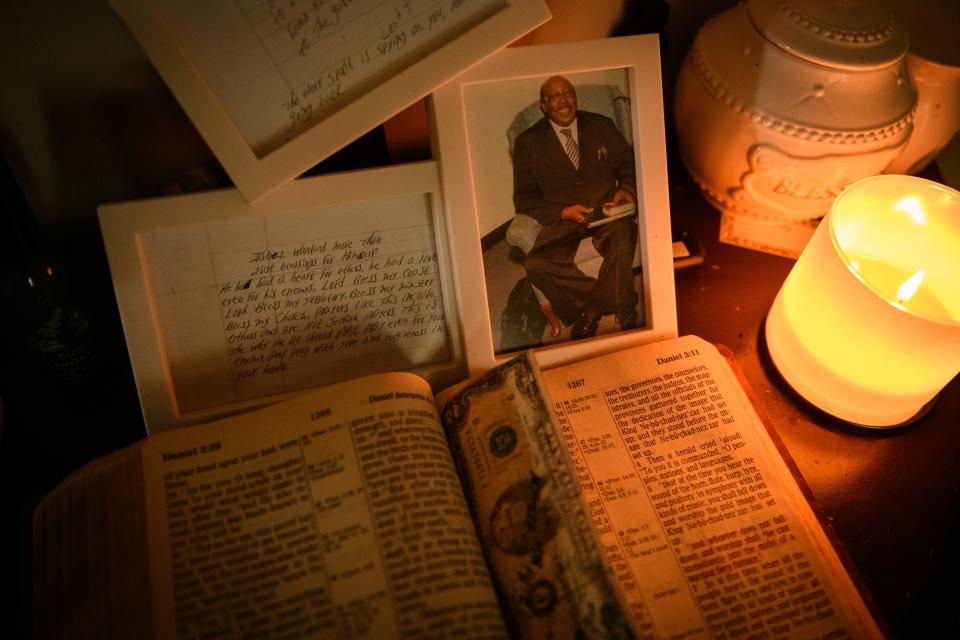

The same day Frink’s father sent him to sit with cattle, he told his son he had stage-four cancer. Before he died, he told his son to look under the third plate in the china cabinet. There he had stashed a plan for his son’s eventual cattle farm, complete with a name — the neighborhood in which he grew up.

“That’s why I love cattle so much," he said. "Because every day I get to be part of my dad.”

One of the babies was born on the anniversary of his father’s death. Happiness on a sad day.

Sometimes friends ask him to dedicate a calf to a lost loved one. Frink does, and sends them photos of the calf as it grows. Sometimes they visit. They say their beloved’s name again. And yes, at the end, the cow is killed and eaten.

They don’t focus on the death, he said. They focus on the healing.

“In life, nothing is promised,” Frink said. "Everything passes away. And we have to have something to get us through these difficult times."

When asked, he pointed out the five cattle he’s chosen for the next slaughter date. All have customers already.

When Frink takes cattle to the slaughterhouse, he walks before them, to take the journey with them.

“I will literally walk that aisle they’re going down to make sure it’s a comfortable feeling for them," he said. "If it doesn’t feel right, we don’t let them get off the trailer.”

At first, the processers thought this was weird. Now they respect it.

There’s a practical reason: If a cow is stressed at the moment of death, its meat toughens. But more than that, Frink thinks it’s important to honor the animal. To honor the sacrifice for nourishment.

Behind him, a cow stood under a shade structure, in labor, surprisingly quiet.

“I still don’t have it all together. I never will. I just want to be part of the solution and not the problem,” he said. “I’m scared to let my guard down. I’m scared to have an interview like this.”

At that moment Briarwood’s lead bull, City Boy, walked up. He ducked his nose under Frink’s hand to ask for rubs, then licked Frink with his thick tongue.

City Boy wasn’t scared.

Danielle Dreilinger is an American South storytelling reporter and the author of the book “The Secret History of Home Economics.” You can reach her at ddreilinger@gannett.com or 919/236-3141.

Uneven Ground: Exceptional Black farmers and their fight to flourish in the South

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: North Carolina veteran helps others find peace through his cattle farm