Cambria’s workers can’t afford to live where they work. Will the local economy suffer?

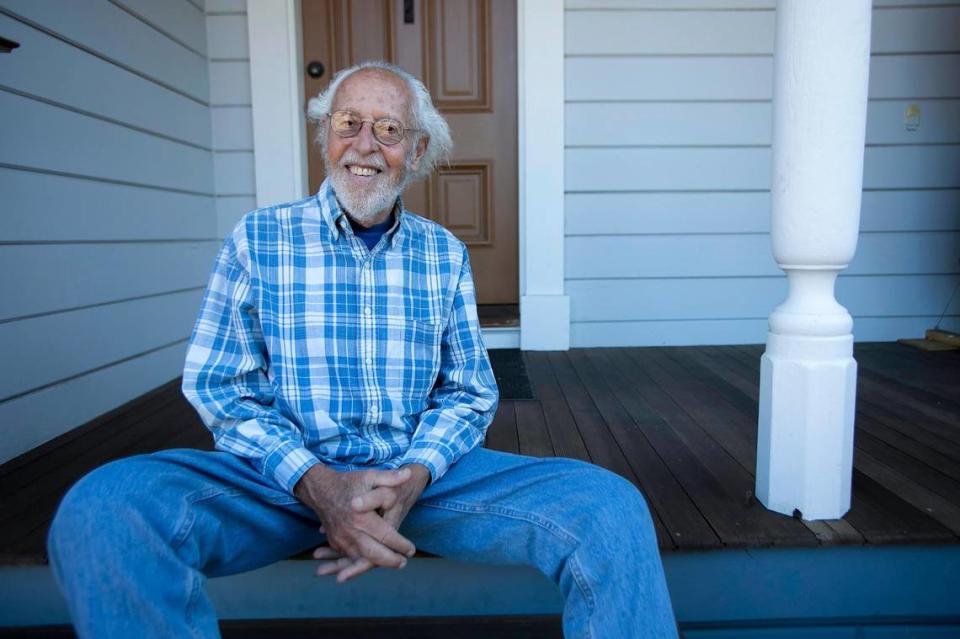

It wasn’t long ago that Mario Leocadio could afford to live where he worked.

Leocadio works at Linn’s Easy As Pie Shop & Cafe in Cambria, and thanks to rising costs of living — specifically, the burden of rent — Leocadio and his family can no longer afford to live in the economy he helps run.

A resident of Cambria since 2001 and an employee at Linn’s since 2017, Leocadio said he made the hard choice to move out of Cambria in 2019 when he and his then-girlfriend decided to get married and start their family.

When the time came to find a rental property to fit their growing space needs, and with a baby on the way, Leocadio said he couldn’t find a place in town in his price range.

“We were looking for only a two-bedroom kind of thing, but since the last five years or so, to get a place to rent is really hard,” Leocadio said.

Cambria has not seen any substantial contributions to its housing stock since the California Coastal Commission’s 2001 building moratorium effectively halted all development in the water-poor community, but now, with rents on the rise across the nation and the vacation rental business doing better than ever, some Cambrians’ budgets are being pushed past the limit.

According to Zillow, the median rental cost in Cambria was $3,200 as of March 25, and Apartments.com listed just one housing unit available for rent in all of Cambria: a two-bedroom, two-bathroom home on Norfolk Street, priced at $2,400 a month.

Leocadio said in his housing search, he quickly came up against some difficulties — namely, extraordinarily high rents, few options and even in one case, a property manager who asked for nearly $10,000 up front for a rental.

Because he and his wife had little credit history, nobody was willing to let them rent without hefty security deposits and rent requirements.

“You had to make triple the monthly rent, but there’s no way you will make triple a $2,000 rent unless you work five jobs,” Leocadio told The Tribune.

Eventually, Leocadio and his wife settled in Los Osos, where they found their current two-bedroom apartment for $2,200 a month, though that didn’t exempt the family from steep prices.

While Leocadio’s wife works in the Los Osos area, he has to commute to Cambria five days a week for work, where his 3-year-old daughter also attends school.

Because Leocadio and his daughter’s start times are staggered by two hours in the morning, he and his wife both make five round trips to Cambria each week, totaling around $200 in gas expenses alone, he said.

“I remember, let’s say, 10 years ago, to rent a place, it wasn’t that crazy,” Leocadio said. “It was a lot easier to get a place — you would sign up for rent and you could get to the house the next day. Now, you’ve gotta go through the paperwork, and ... the first thing they will ask is the credit credit score. If you’re kind of screwed with the credit score, it would be really hard to get a place.”

How bad are Cambria’s water and housing needs?

Historically, Cambria has had very little potable water at its disposal, which caused the Coastal Commission to implement the building moratorium that has prevented the construction of any new water-using developments.

Unlike other SLO County cities that draw their water from lakes or reservoirs, Cambria draws its supply from four wells fed by San Simeon and Santa Rosa creeks.

According to Cambria’s Community Services District, customer demand was about 542 acre-feet of water annually, or about 177 million gallons, in 2022, which far surpasses the 473 acre-feet of water the San Simeon and Santa Rosa creeks are able to supply.

Even with the historic rainfall SLO County received during the winter storms that rumbled through the Central Coast this year, Cambria resident and community service district director Harry Farmer said the moratorium has very little chance of changing to allow more building.

“We’ve been very blessed this year so far to have gotten the abundance of rain that we have, so the wells are doing well, but in the recent years with the drought, we’ve been extremely challenged with regard to water availability,” Farmer said. “This of course has been the trend for decades — that’s the reason that there’s a building moratorium, because the water availability is so unpredictable.”

Ray Dienzo, acting general manager of the community services district, said unpredictability is a significant factor in why the building moratorium hasn’t changed in more than two decades.

Though the recent storms fully recharged Cambria’s creek aquifers, providing Cambria with water for the rest of the year, this doesn’t guarantee the district can supply the town year-round in future years.

“Just to give you an example of how tenuous our supply is, (when) we had a bunch of rains in January of 2021, the creek recharged quickly, but it didn’t rain for a long time,” Dienzo said. “Then the creek aquifer would start to deplete because it needs consistent rains throughout the rainy season.”

Unlike the most recent storms, which flooded the Central Coast for three straight months, in 2021, the rain was far more sporadic, Dienzo said, which did little to help the ongoing supply problems.

Mel McColloch, president of the Cambria Chamber of Commerce’s board of directors, said he’s seen the housing market’s high costs and static size squeeze local employers’ budgets more and more over his 35 years living in the area.

McColloch estimated Cambria needs at least 110 new housing units to keep pace with housing demand in the area. Affordable housing in particular is necessary to support the increasingly financially burdened workforce, he said.

“I think it’s going to be a major problem, because there have already been some businesses shut down from lack of having labor,” McColloch said. “The labor is going to be harder to get, so long term, it’s gonna get worse.”

Local businesses, employees feel strain of high cost of living

For local business owners and their employees, this lack of housing has meant tough conversations about how to make everyone’s financial needs pencil out.

Aaron Linn, owner of Linn’s of Cambria and a longtime resident of the area, said he’s seen the look of the community change over time as a side effect of high housing costs.

“I’ve watched multiple families that I grew up with get out-priced because there’s no additional housing being built,” Linn said. “The value of the homes within town goes up, because it’s finite.”

At his restaurant, Linn said it’s been “almost impossible to raise prices fast enough” to keep up with his employees’ growing financial needs.

That meant raises for his employees and price hikes for the customer, Linn said, largely because it’s become more difficult to retain his current staff or attract replacements when some have been priced out.

Linn said he thinks cost-saving measures such as scaling back wages and some benefits like free meals for staff would likely result in those same employees quitting, a move he hopes to avoid at all costs.

“I know in my heart that at a point my employees are going to say, ‘Wait a second, you used to do this for us (and) now you don’t. I’m just gonna get a job in Los Osos. I’m just gonna get a job in Paso Robles, or in Atascadero,’ where they’re commuting from already.”

Linn said Cambrians who don’t support more housing growth are not “concerned for the economic viability of our town,” and are often the most vocal opponents of new housing development because their stake in the community is already secured.

“They’re the people that have bought a home who are retired, and it’s of no interest to them,” Linn told The Tribune. “The guy next door gets priced out and can’t make a living here because he still has to work, but they’re the ones that have more time to go to the (CSD) board meetings.”

Shanny Covey, owner of Robin’s Restaurant in Cambria, said the labor pool in the area has effectively “dried out” because of the lack of housing, leaving many of her employees to contend with long commutes and the high gas prices that go with them.

Because of the higher number of commuters in her 50-person staff, Covey said she’s felt the pressure to raise wages — though that hasn’t been the only increased cost, with utilities and food prices also on the rise.

“We try as much as we can to be smart with our purchasing and what we put on the menu, so we’re utilizing 100% of the product to try to manage as best we can,” Covey said. “We try to to operate with less bodies whenever we can.”

Covey said she’s been interested in building in Cambria since buying a lot around 30 years ago, but has never seen her number on the town’s development wait list make any forward progress.

“It’s still on the list, and it’s not even getting any closer, so I probably will never get to build on it,” Covey said.

Are vacation rentals to blame for local housing problems?

Even CSD director Farmer’s most recent experience with Cambria’s housing market has been difficult.

With housing drying up, Farmer lost his studio apartment of 29 years when the building was sold to new owners who didn’t want renters.

Farmer said he doesn’t think the building moratorium is fully to blame for Cambria’s housing woes — rather, the vacation rental market is taking too many homes off the board for potential homeowners and renters.

The problem with vacation rentals in the area, Farmer said, became more acute just before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and worsened in the following years.

“It became apparent when folks that were working in the service industry — restaurants, house cleaning, that type of thing — were unable to find affordable housing in this community,” Farmer told The Tribune. “Restaurants were having to close down for lunch, or maybe for an entire day, because they couldn’t get enough staff.”

McColloch agreed, and said the business lost by Cambria’s hotels to independent vacation rentals is a problem for local employers.

According to short-term rental tracker AirDNA, there are currently 244 active short-term rentals in Cambria, with many of these grouped tightly around the Fiscalini Ranch Preserve.

Those rentals are in high demand, too: The average daily rate for these short-term rentals is $362, and they were booked at an occupancy rate of 83%, the AirDNA analysis found.

Even more, 89% of these short-term rentals, were made up of the entire residence, AirDNA said, which suggests that many dwellings operate full time or nearly full time as short-term rentals.

In fact, AirDNA considers 61% of all Cambria short-term rentals to be “available full time,” meaning they were listed as available at least 181 days in the past year.

Beyond immediate availability, this also has long-term implications for other residents in the area.

Linn said many residential properties being used as vacation rentals may not have the same water use as they have in the past, as they are not occupied and consuming water as often.

“Those homes go from 100% daily water use to only weekend water use in many cases, but nobody’s keeping track of how many there truly are, and therefore, nobody’s tracking how much water less we’re using,” Linn said.

The U.S. Census, though unable to provide the number of housing units in Cambria, lists the owner-occupied housing rate at 74.2%, which is far higher than the rest of SLO County.

The county’s owner-occupied housing rate is 62.4%, according to the most recent census, meaning Cambria’s housing stock is comprised of far fewer rental properties than the rest of the county.

How can Cambrian renters stay afloat?

Kevin Kahn, manager for the Central Coast district of the California Coastal Commission, said the building moratorium’s rules are clear: the Coastal Commission has drawn a “pretty bright line” on further building until Cambria has a reliable source of water that will not impact the local creek ecosystems.

Kahn said the Coastal Commission has been supportive of vacation rentals under the California Coastal Act, which encourages the production of “visitor rentals” for vacationers, but may make exceptions in Cambria due to its unique circumstances..

“I would say that it’s a priority for vacation rentals to be provided, and allowed,” Kahn said. “Given Cambria’s inability to produce new housing, I think that we have been more lenient, if you will, or more supportive of tighter restrictions to ensure that (vacation rentals) are not going to convert too many housing units for permanent visitor uses.”

There is one notable caveat in Cambria’s building restrictions, Kahn said: affordable housing.

Provided the development meets “robust water offsets,” Kahn some affordable housing developments are allowed under the building moratorium, which the Coastal Commission allows to keep some amount of workforce housing viable.

In Cambria, the approval process has been long and difficult for developers, People’s Self-Help Housing CEO Ken Triguiero told The Tribune.

People’s Self-Help Housing has owned a piece of property in Cambria since 2006, with a goal of building multi-family affordable housing in the area.

The project picked up steam and was on track to start moving through the permitting process as recently as 2019, Triguiero said, but has since stalled again in the funding stage.

“The last affordable housing that (Cambria) did was back in 1997 — that was the last wave,” Triguiero said. “That’s like ancient history.”

That 1997 affordable housing complex still has a wait list of more than 100 applicants, Triguiero said, many of whom live and work in Cambria.

The more recent People’s Self-Help Housing development is intended to bring 33 affordable units to Cambria, but without state funding, the project remains in limbo for the time being.

With affordable housing effectively at a standstill, Kahn said Cambria, its community services district and the Coastal Commission will need to “get creative” in their implementation of ideas such as creating a system similar to the Los Osos Community Plan, starting a water sharing plan with San Simeon or implementing water recycling and groundwater-recharge programs.

“The status quo isn’t sustainable, so we’re going to have to think of these important and complex solutions, because otherwise, we’re stuck in year 22 and counting (of the) building moratorium,” Kahn said. “That’s not necessarily a healthy way to run thriving communities either.”

Linn said the power to make decisions about building in Cambria “needs to come out of the hands” of bodies like the Coastal Commission due to the unchanging lack of growth, which can be harmful to local businesses.

Until more housing for workers is built, Linn said, the cost of living problems will only get worse for employers and employees alike as the labor pool shrinks to a puddle.

“There should be more say for the businesses remaining economically viable,” Linn said.

If he had the choice, Leocadio said he’d prefer to settle down with his family in Cambria, in a community he loves — but unless things get cheaper, that won’t be possible.

“We’re happy now where we are, even though you’ve gotta wake up 10 minutes before your normal start to get ready,” Leocadio said. “We’re managing to make it work.”