Can Camden, N.J., rise from being ground zero for an entire region's opioid epidemic?

Christoff Lindsey knows, or seems to know, everyone in his Camden, New Jersey, neighborhood. Across the street from the house that’s been in his family since 1960, he jokes with a woman who babysat the 62-year-old. He stops to chat up a man outside a bodega where he gets his morning coffee. They arrange to meet later at one of the community gardens where Lindsey tends to vegetables, herbs and flowers.

He knows the hustlers, the corner boys, the young toughs who sell heroin and other drugs to a daily influx of people coming from all over the region, lured to Camden’s plentiful and potent supply, its proximity to major highways, its vacant lots. He knows the buyers, too: the people, many of them originally from surrounding suburbs, who wander through his neighborhood. They shoot up — sometimes out in the open — nod off on abandoned church steps, leave used needles and orange caps everywhere, weave along streets in varying states of impairment.

He even understands what they’re going through, having lived through his own bouts with addiction and homelessness. But he doesn’t want them here.

“This is our home,” he said. “Go home to yours.”

A city invincible, on its way back from the brink

Camden is a city of about 71,000 people, just across the Delaware River from Philadelphia. Its population according to 2022 U.S. census estimates is 42.9% Black, 52.8% Hispanic/Latin. Just over 33% of its people live in poverty, and the median household income is $30,247, in a state with one of the highest costs of living in the country. Walt Whitman spent his last years and is buried here. The city was an industrial powerhouse in the early 20th century, the birthplace of Campbell’s Soup and RCA Victor. But Camden saw a decades-long decline brought on by the collapse of manufacturing, unemployment, redlining, disinvestment, race riots and many of the other societal ills that plagued post-industrial cities like it across the country.

Over the last decade, billions of dollars in state and federal money, tax incentives for large corporations and investments in parks, schools and public institutions have poured into the city. A “meds and eds” corridor includes the Coriell Institute, MD Anderson Cancer Center at Cooper, a medical school, health and sciences center and a new Rutgers University nursing school. The waterfront has its first hotel in 50 years, and market-rate housing has stoked fears of gentrification in some neighborhoods. “Camden Rising” has been a popular refrain among local leaders, eager to change perceptions of a place that was once described as the most dangerous city in America.

But even as industry returns to Camden, as Subaru of America, American Water, Holtec International and the Philadelphia 76ers make the city their home, some people feel left behind. Residents in some pockets say Camden’s problems remain, pushed into their backyards.

They wonder: Can Camden rise when it’s still ground zero for an entire region’s opioid epidemic, when some neighborhoods still acutely feel the impact of decades of disinvestment, mass incarceration and environmental racism that have hollowed out communities like it all over the United States?

Pushed out, pushed aside

The differences in how addiction is perceived, treated and understood are shown in stark relief in Camden. Its police force was disbanded in 2014 and replaced by a county-run department. The Camden County Police Department, called “Metro” by most residents, places a strong emphasis on community policing, earning the department a visit by then-President Barack Obama in 2015 and glowing national attention during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests when its then-chief, Joe Wysocki, who is white, marched alongside protesters.

Camden’s mayor, Victor Carstarphen, admitted to a learning curve as he transitioned from a career in accounting and finance to politics, becoming mayor in 2021 after a stint as a city councilman.

“I learned that people have to be open to help,” he said. “There are services that are out there in our community; that’s one thing that I know we offer, along with our partners in the county and various nonprofits, that’s consistent.”

The city offers programs to help people at risk for homelessness get back on their feet, connecting families with housing assistance, job placement and training. It takes an individualized approach, Carstarphen said, to identify a person’s or family’s needs and provide appropriate services.

But Carstarphen, a Camden native who was a high school basketball star and later a coach, also noted that addiction and homelessness are two issues that “have no boundaries.”

“Not everyone who’s homeless here is from Camden. We’re constantly trying to build capacity, but we also think every town and municipality has to manage this for their own residents who may be without shelter,” he said. “Homelessness is really a variety of issues: lack of resources, poverty, mental health, substance abuse, domestic abuse.”

Dan Keashen, spokesman for Camden County and its police department, said in an email responding to inquiries that officers “work tirelessly to take poison off the streets of Camden City, and based on the work of the men in women in uniform in tandem with the community, we have made significant progress over the last 10 years.”

Homicides in Camden are down from a high of 67 in 2012 to 13 so far in 2023.

“That said, the drug trade still very much exists here in the city and throughout the suburbs,” Keashen said. “But where we once had 175 open-air drug markets operating with brazen impunity in Camden, that number has been reduced alongside much of the violence. … Our mission is to keep deadly opioids off the streets and make our city a safer place, but that is, and cannot be, solely on the shoulders of just the police department. That mission takes a village with every civic organization in the city playing a vital role and working together.”

Everyday citizens are indeed stepping up to bridge stabilization efforts. Several nonprofits, public works, governmental agencies and grassroots groups operate in the city, many of them focused on either assisting people struggling with drug addiction and homelessness, or improving the quality of life for residents — or both.

A group of Camden residents, concerned with people sleeping, using drugs and loitering in parks, in 2021 launched Not In Our Parks. They organize clean-ups and designate neighbors to keep an eye on these public spaces, working with Camden County Police and social service providers to offer resources to people struggling with addiction and homelessness.

But while a lot of illicit activity has been pushed from the city’s downtown areas, it’s still rampant in Bergen Square and Waterfront South, two areas south of the city’s center.

What lifelong resident Lindsey remembers as “a private ordeal,” the heroin addiction of returning Vietnam veterans, has become a public one in places like Camden and the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, just a few miles over the Benjamin Franklin Bridge.

“Kids (in the neighborhood) are witnessing things I could not even dream of in my nightmares,” he said. “Daily. And it numbs them — it’s not even about normalizing. They don’t know. They don’t have the lines; the lines aren’t blurred.”

There is a disparity in treatment, said Lindsey, who grew up a beloved only child with “no traumas, no abuse” but turned to drugs to deal with feelings of insecurity. “I’m not mad, but the ‘80s and ‘90s addict was a suffering human being as this generation’s is a suffering human being. And they’re not politicizing it to the detriment of the addict the way they did in the ‘80s and ‘90s because of the demographics of the addicts. That has flipped completely.”

Martha Chavis, who lives in Lindsey’s Bergen Square neighborhood, agreed.

Black and brown people were most impacted by incarceration, noted Chavis, who is Black.

“Not for one year, not for two years — for 10 years, 20 years, three strikes and you’re out. Whether you were hauling or using or selling, we were treated very, very poorly; it wasn’t even a matter of being treated.”

Chavis is executive director of Camden Area Health Education Center, a nonprofit housed in a historic building on Cooper Street in downtown Camden, a stone’s throw from Rutgers and City Hall. A small but forceful woman, she talks passionately about her life's work and sees the need for addiction treatment acutely. AHEC offers a syringe exchange program, along with a mobile health van, twice a week.

“When I think about my people in particular, African American and Latinx communities, how they were treated — they weren’t listening (to) the reasons why someone is on drugs, the reasons why someone has to engage in behaviors to maintain their addiction…

“It makes me furious,” she added. “It makes me frustrated.”

She’s been in Camden since 1984 and has been an advocate for the city’s most vulnerable ever since. AHEC offers a host of services in addition to the syringe exchange, including screenings, HIV and PreP medications, counseling for LGBTQ youth and adults and general health care for poor and uninsured people.

“This so-called TV version of someone on drugs, the assumption is that they grew up in poverty, they are under-educated, they are unemployed, they came from a dysfunctional family, they have no job opportunities, things of that nature,” she observed. “But that is not the overall makeup of the population we are seeing through our harm-reduction activities. We find they are educated; in fact, when we survey, we see the majority having high school diplomas. We have people who have served in the armed services, people who have college degrees. It’s amazing the jobs they had prior to drug use.”

In Waterfront South, a historic neighborhood just south of Bergen Square, Bill and Brenda Antinore say illicit activity has been “whipped up out here.”

The couple founded Seeds of Hope, a faith-based organization that helps people through three separate ministries: My Father’s Hands, a homeless outreach; South Jersey Aftercare, a prison ministry and post-incarceration program; and She Has a Name, or SHAN, in which Brenda and a team of female volunteers help women who’ve turned to sex work to support their addictions.

The Antinores have lived in a rehabbed home on Broadway that also serves as the ministry’s headquarters since 2014. Seeds of Hope came about after both Antinores struggled with addiction. Their personal nadir came when Bill, an attorney, pleaded guilty to theft and was imprisoned. The two went from comfortable suburban professionals (trim and fit with short blond hair, Brenda still looks like the high school health teacher she used to be) to a couple dealing with loss, incarceration and recovery through faith.

They knew moving to Camden would come with challenges. But, they said, things have gotten worse over the last couple of years. In August, Waterfront South was designated the city’s first Neighborhood Arts District. However, gunshots are an all-too-regular occurrence. The half-mile stretch of Broadway includes a daycare and community groups, a historic Catholic church and elementary school, an art gallery, a maritime museum, enrichment programs for children, and Seeds of Hope’s own transitional housing for men coming out of prison.

“(Dealers) are selling on the steps of our men’s house where men are trying to rebuild their lives,” Bill said.

“We do love the neighborhood, and I think that’s the hard part,” said Brenda, who, like her husband, has a tattoo on each arm: “loved” and “forgiven.”

“We know the struggle, but it seems like our neighborhood has been left behind,” she continued.

The Antinores have a good relationship with Metro police officers, and appreciate the difficulties faced by cops on the street who often have to be social workers more than law enforcers.

Even enhanced code enforcement, the Antinores believe, would help. In 2020, the city, county and police department teamed to address blight in Waterfront South, an effort to stem illegal activity that often takes place in abandoned lots and decrepit buildings. That effort seems to have fallen off, though, and Bill said he knows of illegal boarding houses that draw drug users and dealers, predatory landlords and dangerous conditions.

“It goes on all day and night,” he said. “We’ve got things here, just in this quadrant, addresses that are just dens of iniquity. … That stuff needs to be addressed, not just because it’s dangerous to the occupants who are being taken advantage of, it’s dangerous to people in the surrounding houses.”

Their ministry’s vans have been sideswiped by impaired drivers, they said. Last year, a woman seeking refuge at the Antinores’ house after “some kind of transaction gone bad,” as Brenda described it, was chased by a knife-wielding assailant. Their adult son tried to intervene and was stabbed as his wife and young child looked on, horrified. Bill and Brenda, meanwhile, were coming home when they saw a man in distress on the sidewalk around the corner, so they were busy calling for help and seeing if he needed to be revived with Narcan. (Their son was hospitalized and recovered.)

“I know everything got turned upside down with COVID,” Brenda admitted. “We’re very hopeful and want to remain hopeful, but I feel like we’re at the furthest point away (from the revitalization efforts downtown) and we’re like, ‘Are we going to get stabilized here?’”

‘The living room’ for a region

According to New Jersey’s Point In Time Count of homeless people, Camden County has 491 homeless people, 136 of whom are considered unsheltered. A vast majority of those people, 108, self-reported having substance use disorder. The City of Camden has 116 unsheltered homeless people.

Chavis called the city “the living room” of Camden County and the South Jersey region. There are homeless shelters, free kitchens, a methadone clinic and social service agencies, as well as the usual features of a county seat.

“Because we are the county seat for our government, our court system, our jail system, for our prosecutors and overall law enforcement, we are in this constant ongoing relationship. As many as we get into recovery, as many as we get off the street and into treatment, you have as many coming in.”

The “living room” can be quite a place, Chavis admitted. She recounted an incident from just days prior.

“Individuals, and I know one of them, at least, is using drugs, were engaged in a sexual activity right outside my house. They woke me up!

“Sometimes when I get home, I will say, ‘I hope nobody’s going to be asking me if I have a couple of dollars.’”

She’s seen Camden’s revitalization efforts — not just the new office towers downtown, but also the investments in new parks and green spaces, the efforts to crack down on illegal dumping that plagues the city’s vacant lots, demolition of abandoned homes and factories that draw crime and blight to Camden.

“As much as the city’s done, I don’t want to go down to an area that’s been cleaned and see it trashed again because we have homeless individuals. That’s what makes this place the living room — people live here, but other people come and go and they don’t stay, you’re not settling in, you have no stake, you’re just using it for the moment, until your next step or your next fix or the bus drops you off at 7:30 and your appointment (with social services or treatment or health care) isn’t until 10, or you’re standing in line for a meal… that’s our ongoing reminder.”

She echoed Lindsey, whom she knows from the neighborhood: “That’s how we all feel here in Camden. We all have our worries and concerns, because we’ve had family and friends out there. But we think, yeah, go home, let’s get you some help.”

Lindsey has found used needles at seemingly every turn: near the house his grandmother bought from a man who’d been born there, and where Lindsey was raised. In his garden, empty lots on either side of the house. Next to (and sometimes even stuck in) the trees he planted along the block of Walnut Street. In front of the Book Ark, Camden County’s version of a Little Free Library, where he stocks children’s books and reading material he thinks his neighbors might like. Some of the needles, he said, still have blood in them.

Walking around his neighborhood in his trademark Crocs, Lindsey stopped in front of a long-vacant school. Orange caps and spent syringes lay on its steps; a pile of what looked like human waste was on the sidewalk next to the steps. Lindsey remembered playing basketball in the schoolyard; he talked about the city’s history and how different ethnic groups — Black, Polish, Italian, Jewish, Latino —- would live and work in separate neighborhoods. Two men staggered past on the other side of the street. A woman walked past, her arms wrapped around her on a hot, humid day. Lindsey asked how she’s doing. “Not good,” she answered. “Do you have any water? I really need some.”

He didn’t, at least not with him.

The people at Exit 4

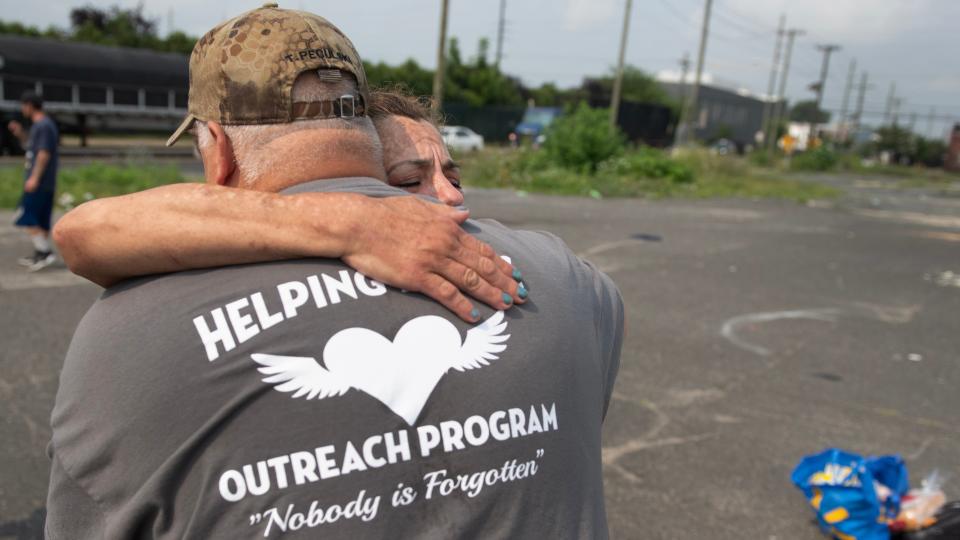

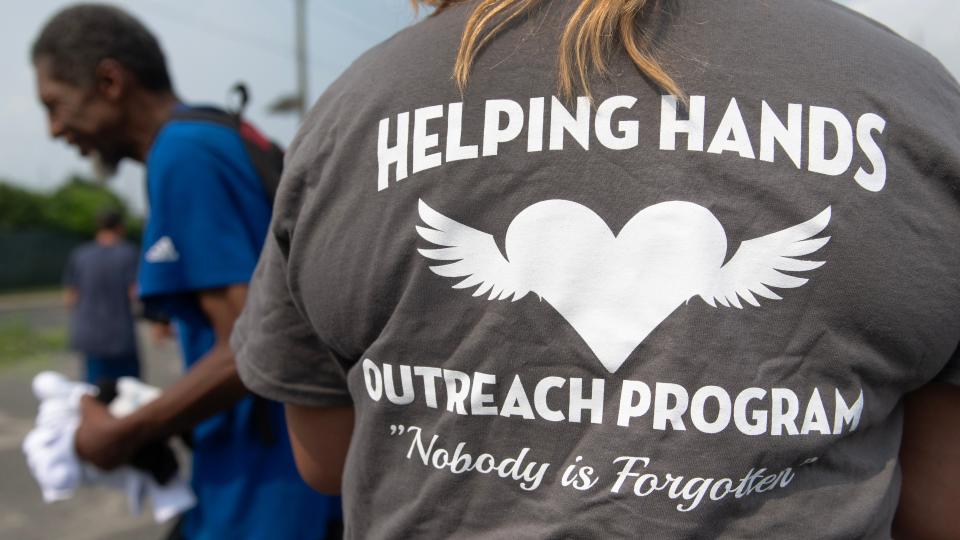

It was a hot, humid morning and Tom Peculski, a retired EMT who leads Helping Hands Outreach Program, started unloading his car. As he pulled out bottles of water and Gatorade, socks, snacks and personal hygiene items, people started to gather in the rough lot on Atlantic Avenue. Joseph’s House, an overnight shelter, is just down the street, as is the methadone clinic that drew strong neighborhood opposition when it relocated from Downtown Camden.

But many of the people Peculski and his volunteers help don’t stay at Joseph’s House. Instead, they live in tented encampments, especially along the wooded areas around I-676. Some encampments are hidden deep in the woods or under overpasses; others are more easily spotted — if only by those who want to see them.

“People aren’t coming to Exit 4 for the beautiful scenery,” deadpanned Peculski, a burly guy with the unflappable demeanor of someone who’s spent a career in stressful situations. “They’re coming for the drug sets.”

Peculski has used his training to save people from overdoses in the camps and has also discovered those he never had a chance to save. He said he has one overriding frustration: the drug sets operating with apparent impunity. That frustration is compounded because, he said, homeless and addicted people are constantly roused, chased and harassed by police.

Large, loud trucks rumbled past, on their way to and from I-676 and heavy industry: a major auto recycling facility, a trash-to-steam plant, a steel yard and the South Jersey Port Corporation.

“Everybody knows what’s going on out here,” Peculski said. “But it gets ignored. … Every (encampment) they have cleaned has been reoccupied. They just sweep people to a different corner, a different block, or they just wait and come back. That’s where we are in this tug-of-war.”

“Country,” whose given name is Vincent White, has been on the streets of Camden off and on for two decades. Though he struggled with crack and cocaine addiction in the past, he said he’s clean now except for drinking “from time to time.” His homelessness, he said, stems from depression, suicide attempts and physical ailments. He’s known as an informal mayor for many homeless people in the area, someone who can help newbies acclimate to life on the streets, but who also acts as a go-between with service providers like Peculski.

Country said when an encampment is cleared — especially without warning — people’s meager belongings are often thrown away or lost. That can include not just their tents, coolers and clothing but also necessities like identification, maintenance medications and phones.

One man, Pete (who asked that his last name not be used), said police threw away his inhaler, even though he told them he needed it for his asthma. Melanie, who’s been on the streets since her husband died in 2017, said she’d gone through 22 phones. She sobbed as she talked about having “a beautiful home” in Runnemede, a nearby suburb, and about her oldest son who is on hospice after medical complications from a motorcycle accident.

Kerri and Josh live in their own well-hidden encampment, with plastic gates to keep out raccoons and skunks that sometimes try to raid their supplies. A dozen or so needles were arranged on a cooler as the couple from Williamstown, about 20 miles away, talked about their nine months on the streets.

“We were clean in Williamstown,” said Josh, who used to work in construction.

“You don’t want to do this sober,” said Kerri, her blond hair tied on the side of her face. “There’s always people out here asking for something. Like, I’m homeless out here with you, you think I have something to give you?” People call her “junkie” and “fiend,” she said. Teens sometimes throw rocks at homeless people and steal from their encampments, Country added.

Another man, Mike, said he is on Suboxone as he tries to get off heroin. Most residents are tolerant of the homeless people, even sometimes paying them a few dollars to do yard work, he said.

“Most residents don’t have a problem with us, as long as you keep moving, as long as you don’t use at their houses or in front of their kids,” Country said.

Asked how they get money to buy drugs and food, Josh said he buys things cheap and resells at a markup. “Prostitution, sometimes, but only as a last resort because…” admitted Kerri, averting her eyes and squeezing Josh’s hand.

Seeing conditions in the encampments, it’s easy to imagine how despair can set in. There’s a lot of trash. There’s constant noise from the highways and streets. And people are vulnerable to theft, violence and sexual assault. New Jersey summers are brutally hot and humid, while winters can be frigid. Just the week before, Country found a young friend in the encampment dead, presumably from heat stroke because “he kept his tent all wrapped up tight to keep the bugs and animals out, and that’s how I found him.”

“You get caught in a cycle,” Country explained. “The cops are always running you off, and it can only take a moment to lose everything. (Homeless people) might come out here just using casually, but if you don’t have a place to rest, a place to keep your things safe, anywhere to sleep… Just because we’re homeless, don’t make us hopeless. We’re human, just like everyone else.”

Camden County’s Addiction Awareness Task Force and Office of Mental Health and Addiction work with several non-governmental agencies and nonprofits on education and prevention efforts, said Keashen, the county and police spokesman.

“Many of our officers have provided time and resources well beyond the call of duty to assist and help the unsheltered in our community,” he continued in an emailed response to questions.

“Nevertheless, we know more can be done,” and it will. He said social workers would soon be part of the police department, and existing programs would be improved and expanded “to get the unsheltered back on their feet and into stable housing.”

During an outreach event in July, Keashen pushed back against claims that homeless encampments are cleared without warning, or that homeless people were harassed or cited by police simply for being homeless. Cleanouts often happen after a fatal overdose or overdoses, he said.

“We can’t turn a blind eye to a public health hazard. The base of our job is to save lives,” he said, adding that the county subsidizes or pays service providers. Three to four weeks' notice is given before a cleanout, Keashen said.

“By the point law enforcement gets involved, you’re dealing with the very last subset of people in an encampment.”

‘The fruit of the problem’

Camden County supports a host of programs and initiatives to get people off the streets and, when needed, into detox and addiction treatment, said Rob Jakubowski, who oversees homeless outreach and community development.

“Camden County Police, Camden DPW, they may not be social workers but they are some of the most caring, compassionate people I know. They care deeply,” Jakubowski said.

Homelessness, Bill Antinore believes, is not the problem but “the fruit of the problem. And everyone is talking about the fruit of the problem, but we need to attack the root of it.”

“People are in hopeless places,” Brenda added. “Pain is a great equalizer and a lot of people find themselves engaging with (drugs) as a result of emotional pain, never realizing it’s going to devastate their life. So to purvey hope is extremely important.”

The Antinores stressed the need for relationship building, and the reality that recovery is seldom a straight line from self-harm to complete healing. Decades into their own recoveries, they both still see counselors.

“You can’t pull out and you can’t give up,” Brenda said. “When they start, when they fall off, that person already feels bad so we have to be good agents of restoration. We continue to stay alongside them and encourage them to get back up.”

Their ministries are able to get people help immediately, something that wasn’t the case in the beginning, Bill said.

“The lie is, they’re not here because we’re providing (services and outreach),” Brenda said. “There are people here providing things because these needs have been identified and they’re only increasing.”

Chavis, who runs the healthcare clinic and syringe access program, said faith-based and secular nonprofits all over Camden deserve credit for the many programs they offer, and the many ways people can get help. She believes there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to recovery and sees an advantage to the diversity of options for people who need help.

“So I think that is a nice base, a foundation where we’re more into hope, encouragement and optimism.”

She’d like to see more collaboration, more sharing of data and best practices among providers, but most of all, more resources to help young people cope with anxiety, depression and low self-esteem so they can turn to healthier coping mechanisms. She likens drug use to smoking: As education about the dangers of tobacco spread, fewer kids picked up the habit and more adults began quitting, until just 11.5% of Americans now smoke, according to the CDC, compared to nearly half the population in 1950.

From handcuffs to helping hands

It was another warm morning that would become a hot, humid day, and a small army of outreach workers started setting up tables at Broadway and Chestnut streets, just a block from where Chris Lindsey recalled playing basketball.

A Camden County Health Department van pulled into the vacant lot, and as soon as workers began moving about, people approached. Also setting up shop: Center for Family Services, healthcare workers with Cooper University Hospital, We Level Up Rehab and Detox and Maryville Addiction Treatment Center.

“We’re not really here to solve homelessness,” admitted John Pellicane, director of Camden County’s Department of Mental Health and Addiction. “It’s more about mental health and addiction, and connecting people to services,” including detox, addiction treatment, health care and social services. The Sheriff’s Department is available to help people secure documents like government-issued IDs; there’s also help connecting people with Medicaid and other assistance.

Pellicane said “a significant number” of the people who come out to the weekly outreach are homeless. Many of the nurses with Cooper, which has its own addiction treatment programs, have provided wound care as xylazine, known on the street as tranq, has infiltrated Camden’s drug supply.

An hour into the outreach, a man collapsed in the middle of a busy intersection nearby. Nurses rushed to render aid; a Cooper ambulance responded. It was unclear whether he’d collapsed due to an overdose, another medical emergency or simply the 90-degree heat and humidity. As others worked to revive him, eventually putting him on a gurney and into the ambulance, an outreach worker noticed the man’s belongings in a battered shopping bag. “This is his stuff!” the worker shouted to the EMTs before they left. “Make sure he gets his stuff!”

Vivian Coley, a captain with the Camden County Police Department who oversees its community policing initiatives, said as residents complained about encampments, trash and drug paraphernalia, “we knew we had to do something more.”

“So we reached out to John Pellicane to see what solutions we could come up with. A lot of the people we see out here aren’t from our city. We’re trying to stop the (drug) dealing, but we have to offer help and services to the people who are buying.”

Coley, a Camden native and resident who worked for several years in the police department’s Special Victims Unit, said 60 to 80 people show up at the outreach, which typically happens Thursdays from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. The department is planning to expand the outreach to other locations on other days, she added. Her officers hang back, trying not to scare away people for whom police interactions are problematic and letting outreach workers do their thing.

Richard Buckman, a peer recovery specialist with Maryville, said he stopped using PCP 17 years ago when his son, then very young, confronted him. Becoming emotional, he talked about his reasons not just for getting and staying sober, but also for the work he does.

“This is personal and professional to me,” Buckman said. “I know the ins and outs, the denial… I can’t save everyone. I call myself, all of us who do this, undercover Superman, but I also know even Superman can’t save everybody.”

He wants people to know there is life after addiction.

“I tell people, I’d rather see you 6 feet up than 6 feet under. The choice is yours. Maybe 7 in 10 eventually seek help, and I do see success stories. I tell people, if you make it out, pay it forward and let people know you care.”

If there’s one thing everyone — police, outreach workers, medical professionals, addiction specialists and even residents — agree upon, it’s that it takes time, trust and patience to convince someone to accept the help that’s offered. One thing they all agree on, too, is that the help is there, far more so than in the past.

Carstarphen, the city’s mayor, said Camden’s revitalization is a work-in-progress, but one that’s driven by its people.

“You can never rest in trying to make your community better, but the little things like clean-ups start to reverberate. We’ll continue to move the needle in a positive direction,” he said.

Lindsey, the urban farmer and amateur arborist in Bergen Square, like the peer recovery specialist Richard Buckman, said he wished more people realized there’s life after addiction – a fuller, better life.

“There’s help. There’s a better way to live. … If a hand is offered to you, take it.”

Like the Antiores, like Chavis, like Peculski — even like Carstarphen, who sees brighter and better days ahead for Camden — he wants to be a purveyor of hope in his community.

“All we have is each other, here in Camden and everywhere," he said. "If I had the means to help everyone, I would,” he said, preparing to go back to his small urban farm to grow cabbages, zucchini, peppers and other produce he shares with his neighbors.

“I don’t. But I try to make a difference here.”

So all of Camden can rise.

This story was created as part of a Gannett Northeast Region How We Live Fellowship under the direction of Jamesetta M. Walker. Phaedra Trethan can be reached at ptrethan@gannettnj.com, or on X, formerly known as Twitter, @wordsbyPhaedra.

This article originally appeared on Cherry Hill Courier-Post: Can Camden, NJ, rise while opioid epidemic plagues neighborhoods?