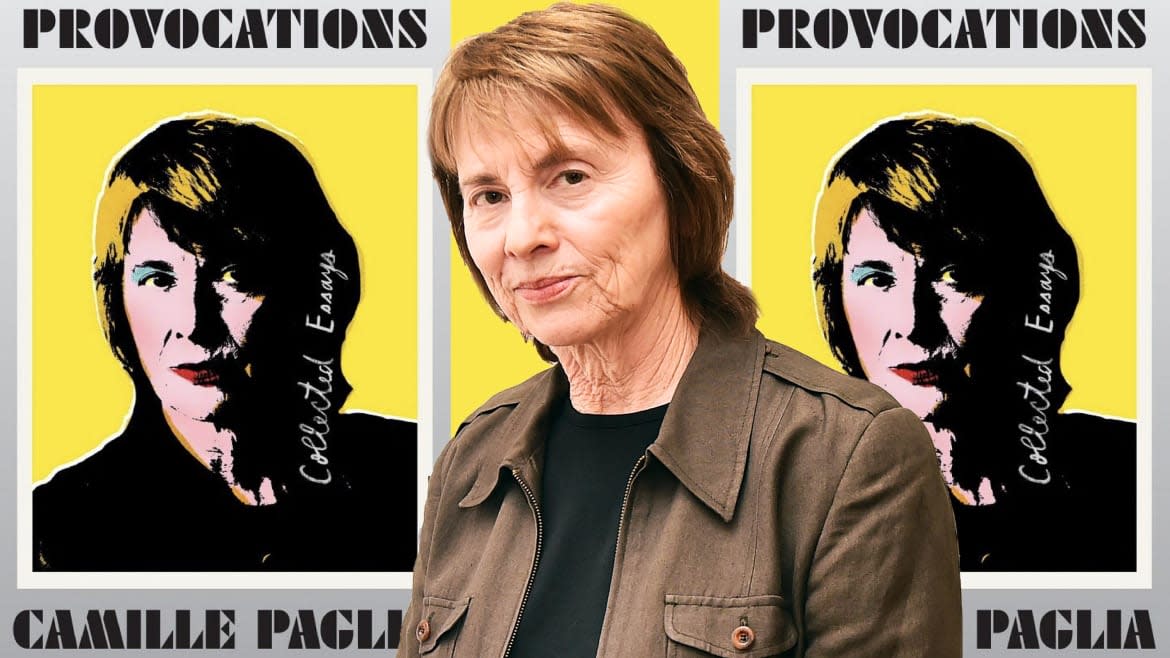

Camille Paglia Wants to Provoke, but Mostly She Just Irks Us

On so many issues, Camille Paglia and I are simpatico. We believe in free thought and free speech, we root for the Philadelphia Eagles, we dig Rihanna, we think comparative religion should be part of a core curriculum, we loathe modern French literary theory, and we agree that “Anarchism is glorified thumb-sucking.” Our ancestors were peasants from southern Italy. And we are both huge fans of her classic, Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson.

It may be hard for younger readers to appreciate the impact that Sexual Personae had in 1990. Those old enough liken it to the effect of Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation in 1966. An exhilarating swirl of decadence, sexual politics, and revisionist art history, Sexual Personae bitch-slapped a stuffy and complacent academia. Opening its pages was the intellectual equivalent of finding foie gras in a high school cafeteria. It was as if Nietzsche had a lesbian Italian sister.

It’s been nearly thirty years since Sexual Personae. We’ve waited for the next thunderclap from the Ubermensche Frau. But what we’ve gotten after all that time is a pundit. Provocations is 712 pages, a collection of Paglia’s essays, Salon columns, interviews, and even one hundred pages headed under the title “A Media Chronicle” of everything written by or said about her over more than two decades.

The big pieces—“Erich Neumann: Theorist of the Great Mother” (a compact and concise introduction to the exemplar who “became Jung’s intellectual heir), “Slippery Scholarship: Review of John Boswell,” “Same-Sex Unions in Pre-Modern Europe,” “Intolerance and Diversity in Three Cities: Ancient Babylon, Renaissance Venice, and Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia”—are welcome and might be more so if collected into a fine, neat volume. (Though I would not include “Homer on Film,” a bizarre, 33-page review of four bad movies on classical subjects that no one will ever watch.)

On these subjects Paglia is in her element and writes with such assurance that you feel she can illuminate them better than anyone else. But less of Provocations would have been more.

In Break, Blow, Burn, her 2005 commentary on 43 great poems, she comments that it “may be the only book of poetry criticism that has ever reached the national best-seller list in the United States,” a Trumpian-like boast that is nonetheless probably true. Her choices, from Shakespeare to Donne to Yeats, can’t be faulted, but when she gets further into the 20th century, there are huge, yawning gaps.

I’m fine with her excluding Ezra Pound (“a monotonous series of showy, pointless, arcane allusions to prior literature”) but I’m dumbfounded by the absence of W.H. Auden because “few of his poems can stand on their own in today’s media-saturated cultural climate.” (I’ve no idea what that means.) Philip Larkin and Louis MacNeice aren’t even mentioned. Robert Frost, who Clive James would “put forward as the greatest modern poet of them all,” is rejected for what she calls his “pious platitudes.” These are serious lapses of judgment.

In another terrible decision, she insults Seamus Heaney, “who enjoys an exaggerated reputation for... middling poems that strike me as second-or-third-hand Yeats.” Yeats? Is it possible to name a poet whose ability for evoking the artless beauty of rural life makes his work less like Yeats’? (Yes: Robert Frost.) Only one Irish genius allowed per century.

I skipped the chapter on her selection process. I wish I had skipped it a second time in Provocations.

As her subtitle indicates, Paglia takes on a broad range of subjects. But as a critic of literature, she has more blind spots than an NFL official. She doesn’t read modern fiction—“I don’t care about any novels published after World War II,” so much for Nabokov, Garcia Marquez, and Bellow—and has no affinity for any modern playwright except Tennessee Williams (“my main man”).

As to film, she gives a nod to Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather movies and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, but little since Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966) has floated her boat. “Art movies are gone, gone with the wind,” which strikes me as an odd epithet for the art film, but to each her own. The new wave of American films from Bonnie and Clyde (1967) through the end of the ’70s made no impact on her. No Robert Altman, Martin Scorcese, or Sam Peckinpah. Not even the films of David Lynch, which surprises me; I thought Mulholland Drive would be right up her Freud-friendly alley.

The only 21st century film which draws an unqualified rave is George Lucas’ Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith, “which will remain a classic, beloved by worldwide audiences...” Remain beloved? The movie got a 65 percent score from a very friendly audience the year it was released.

Like Sontag (who once asked rhetorically “Why can't I love Dostoevsky and The Doors?”), Paglia drops rock and pop names as a way of validating her street cred. She knows a lot more about music than Sontag ever did, and her taste is pretty good, but we seldom get any critical insight beyond assertions of her “exacting high standards.”

Those standards are no longer met by Madonna, whom she once called “the future of feminism” in The New York Times. But in 2017, Madonna “struggles to regain the creative brilliance and global impact of her early years.” Perhaps Paglia was still ticked off at her for not wanting to get together years ago: “I was Madonna’s first major defender... The media, in the U.S. and abroad, constantly asked Madonna about me or tried to bring us together and she always refused...”

Madonna should have taken the get-together. David Bowie listed Sexual Personae as one of his favorite books, and in return Paglia writes, “It did not surprise me: that great artist was sensing himself mirrored back from my pages.”

Some of her generalizations on popular music stretch to the breaking point: “Folk and rock music, emerging from both black and white working-class traditions, were the vernacular analogue to William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s epical Lyrical Ballads ...” But I don’t see how John Clare leads me to appreciate Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly. We both love many of the same songs, including Rihanna’s “Pour It Up,” but Paglia doesn’t tell us much about why, except “I think it’s a true work of art.” She writes about pop music artists like a priest anointing saints.

Bob Dylan’s “Desolation Row” isn’t just a great song: “I submit that this lyric is the most important poem in English since Allen Ginsberg’s Howl…” She would “classify Prince as a major artist of the late twentieth century.” Patti Smith’s 1975 album Horses “remains one of the greatest products of the rock genre.” Chaka Khan’s “Ain’t Nobody” is “a masterpiece of modern popular culture...” “Goldfinger” by Shirley Bassey is “the most terrifying manifestation of ruthless star power ever recorded.”

When Paglia writes at the top of her voice like this, it sounds like she’s trying to say everything without actually saying something. I agree that Adele’s “Rolling in the Deep” is a killer, but what does it add to say it “recapitulates the entire history of black music”? Can’t I enjoy it without seeing images of Buddy Bolden, Robert Johnson, and Thelonious Monk floating by?

We’ve always read Paglia for her inventiveness and unpredictability, but over the last couple of decades, the unpredictability has become predictable. Paglia’s opinions in Provocations are filled with scattershot observations on matters in which she seems more passionate than knowledgeable. Such as ...

—Global warming is “a sentimental myth unsupported by evidence.” “I have been highly suspicious for years,” she tells us, “about the political agenda that has slowly accrued around this issue. From my perspective, virtually all the major claims about global warming and its causes still remain to be proved.”

I’m no expert on global warming—it’s possible that I know even less about it than Paglia does—but I know a little about the so-called political agenda that has “accrued around” global warming, namely that since conservatives won’t accept scientific opinion on this issue, anyone who even entertains the notion that global warming is real is by definition a liberal.

—“Guns are not the problem in America, where nature is still so near. These shocking incidents of school violence [such as the Columbine massacre] are ultimately rooted in the massive social breakdown of the industrial revolution which disrupted the ancient patterns of clan and community ...”

I don’t know what nature has to do with our gun problem, but I know that people in Canada, Australia, and a lot of other places are at least as near to nature as we are, and they don’t suffer mass shootings. The recent tragedy in New Zealand was the first mass shooting in that part of the world since the 1996 massacre of 35 in Tasmania, which prompted quick gun law action in Australia just as New Zealand has now responded with similar legislation.

—Ayn Rand. “The kind of bold female thinker who should immediately have been a centerpiece of women’s studies programs, if the latter were genuinely about women rather than about a cliched, bleeding-heart victim-obsessed, liberal ideology that dislikes all concrete female achievement.” I assume Paglia hasn’t read Rand’s novels (including The Fountainhead, which Pauline Kael called a “megalomaniac comic book”), so she must be talking about the rigid ideology of a humorless, puritanical didact whose most prominent disciples in our time are Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck. If Paglia truly regards Rand as a “bold female thinker,” why does she relegate Rand to the children’s table of women’s studies? Would Paglia take Rand’s work seriously if it had been written by a man?

—Princess Diana. “Diana had a burning but erratic energy, like that of the great Hollywood stars... Diana will have eternal life through her resurrection in the innumerable documentaries... The photogenic Diana made an immense contribution to world visual culture, in my view exceeding the work of painters and sculptors as well as most filmmakers in the same period... Diana has been absorbed into world myth... Her saga will become archaeological, like the love stories of Victoria and Albert or Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson... Since there are no celebrities left of Diana’s stature, we are mesmerized by a vacuum.”

Does Paglia have no one who will tell her that this kind of writing is kitschy, myth-mongering supermarket tabloid gush? I’m dumbfounded as to why she would associate Diana with two Nazi sympathizers.

—Sarah Palin. “The gun-toting Sarah Palin is like Annie Oakley, a brash ambassador from America’s frontier past.” Annie Oakley grew up in Ohio and spent almost her entire life in the Midwest or East and saw almost nothing of the frontier. And Sarah Palin’s parents were educators, not ranchers. Palin spent a couple of years competing in beauty pageants while attending several different colleges (including two in Hawaii) and is no more an ambassador from our frontier past than Hillary Clinton.

—War. Gone With The Wind “beautifully demonstrates the horror of war. Everyone is so wildly enthused for the war at the start, but Ashley Wilkes says, ‘Most of the miseries of the world were caused by wars. And when the wars were over, no one ever knew what they were about.’” This is drivel. The great misery of Ashley Wilkes’ world was slavery, and it was ended by a war, not caused by it.

—Taylor Swift. “An obnoxious Nazi Barbie.” I can’t imagine what Taylor Swift could have done to provoke such a vehement reaction from anyone, with the possible exception of Tom Hiddleston. As Clive James observed, Paglia “has a taste for bitchery but no touch.”

—Genius. In Salon, she rattled off a quick roster of 20th century geniuses—“Pablo Picasso, Igor Stravinsky, James Joyce, Martha Graham. Claims could also be made for Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Alfred Hitchcock, Jackson Pollock, Ingmar Bergman, and Bob Dylan.” Her list strikes me as both obvious and arbitrary. Where are Kafka, Yeats, and Proust? Hitchcock, but not Orson Welles? Duke Ellington and Miles Davis, OK, but surely the most influential jazz musician—maybe the century’s most influential musician in any form—was Louis Armstrong. Bob Dylan, sure, but since I’m from Alabama, could I raise a hand for Hank Williams?

***

Too many of the pieces in Provocations are hastily thought through and shoddily written. In an interview with the Columbia Journal, she admonishes young writers who “don’t know English well enough... they don’t care with individual sentences or paragraphs.” She would have benefited from having a student from the Columbia Journal read through her own copy before it went between covers.

For instance, her maddening overuse of “ly” words. If Nabokov or Hemingway (who surely would have agreed about nothing else) had edited Paglia, they’d have red-flagged hundreds of cases of adverb abuse. To note just a few:

“Dramatically demonstrates,” “wonderfully catches,” bloodily jammed” (all p. 88), ”barbarically sensual” (p. 90), “grotesquely overblown” and “densely visualized” (p. 113), “chillingly archaic” (p. 115), “interestingly ghoulish” (p. 118), “admirably captures” and “grittily building” (p. 122), “very authentically beating” (p. 123), “sweepingly scored” and “gorgeously ornamented” (p. 126), “instantly smitten” (p. 127), “standing eerily” (p. 128), “blindingly charismatic desirability” (p. 130). Vivien Leigh in Anna Karenina is “beautifully controlled” (p. 123), and Kirk Douglas as Odysseus is “charismatically convincing.” (p. 128) Can someone be charismatically unconvincing?

A character in a version of The Odyssey is killed by “an arrow gorily piercing his throat.” Do we really need “gorily”? Another character “narcissistically primps.” It would be better to say primps narcissistically, but better still not to write it at all.

Paglia is too easily stunned. Dylan’s “Desolation Row” is “a stunning achievement.” A scene in Truffaut's Jules and Jim is “stunningly successful.” European art films achieved “a stunning sexual sophistication.” The poems of Theodore Roethke were “a stunning departure” from what she had been taught in school.

When groping for an insight, Paglia has a frustrating habit of falling back on her heritage, “that stately, archaic sense of time in my Italian grandmother’s kitchen when I was a small child in upstate New York.” Her Italian-ness enables her to understand death: “The steely Italian stoicism and even irreverence about death have often gotten me into trouble in American academe ...” It helps her better understand celebrities, even those of Polish heritage like Martha Stewart (“As an Italian-American, I had an immediate vibe with Martha Stewart ...”) and Iraq (“It’s a cauldron of warring tribesmen... I understand it from my family background in Italy... it’s a tribal memory.”) and even concrete: “In Italian culture we pay attention to infrastructure... The Romans developed concrete. In my family—oh my God—they could talk about concrete forever!” (I wonder if her family read Pietro di Donato’s Christ in Concrete, the only novel anyone in my family read before The Godfather. Paglia thinks that we “are the most defamed minority group (after blacks).” Maybe, except for Jews, Poles, Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, Muslims, and gays.

Far too much of Paglia’s time is taken up in political punditry, a field for which she has no talent. For someone who claims to be a registered Democrat, she sure sounds like she’s lobbing Molotovs for Fox News.

“Why,” she wrote in Salon in 2009, “has the Democratic Party become so arrogantly detached from ordinary Americans?” The Democrats are so arrogantly detached from ordinary Americans that they’ve given them the GI Bill (which boosted an entire generation of working class families into the middle class), Social Security, Medicare, welfare, unemployment benefits, and health care, most of which the other party has relentlessly tried to cut back or abolish. I can’t believe that at least some of Paglia’s family didn’t benefit from one or more of these programs, as mine did.

Paglia uses the terms identity politics and political correctness the way my cousin Bart uses parmesan cheese. As for PC, she is right to ask, “Has campus leftism in the U.S. been so transformed that it now encourages, endorses, and celebrates suppression of ideas ... ?” The answer is yes. But whose politics and whose idea of correctness? Political correctness is a door that neither side wants to swing both ways. I don’t see Michelle Wolf and Amy Schumer on Fox News, or Jim Jefferies doing his gun control routine at Liberty University or BYU.

As for identity politics, when fresh out of college I worked for the Republican Party, and one of the first things I was told was to remember that “All politics is local.” This was code for white politics, which somehow is never acknowledged to be a form of identity politics. Let’s face it, in America we have a shorter term for identity politics: politics.

Paglia’s bad political instincts congeal around Trump. Again, in Salon she writes, “Wow, millionaire workaholic Donald Trump chases young, beautiful, willing women and liked to boast about it. Jail him now!” This dismisses nearly two dozen unwilling women who have accused our president of sexual misconduct (and I haven’t a clue as to why she associated workaholic with Donald Trump, who doesn’t seem to have done a day’s work in his life).

She gets a charge out of Trump saying John McCain “isn’t a war hero, because his kind of war hero doesn’t get captured—that’s hilarious! That’s something crass that Lenny Bruce might have said! It’s so startling and entertaining!” No, I don’t think Lenny Bruce would have said that; Bruce volunteered for the Navy during World War II while Trump successfully evaded the draft five times during Vietnam. I think Bruce might have pointed out that you can’t get captured if you don’t serve.

Liberal Democrats, she thinks, classify Trump voters as “racists, sexist, misogynistic, and all that.” By knocking down a straw man, Paglia obscures the obvious fact that so many racists, sexists, and misogynists are Trump voters. Or perhaps the TV cameras are lingering too long on the Confederate flags at his rallies.

When she talks about her politics, many critics follow Paglia’s lead and classify her simply as a “contrarian.” But they let her off too easily. This, from a 2003 interview, is typical of her political pronouncements: “I’m a libertarian Democrat who voted for Ralph Nader.” I suppose that is contrarian, but it’s contrarian in the sense that Paul Berman nailed when writing in Salon about Nader supporters: “I interpret the Green Party as a movement of the middle and upper-middle class, as actually having a certain satisfaction with the way things are—which is to say, the reason you should vote for the Greens is because you want to feel the excitement of political engagement... but you don’t really care what it’s going to mean for other people if the Republicans get elected.”

Maybe it’s not fair to judge Paglia by what she wrote a year before the Trump administration caged hundreds and perhaps thousands of immigrant children; ignored the murder of a journalist, an American resident, probably because of financial considerations; and caused unwarranted suffering to hundreds of thousands of government workers and their families by cutting off their salaries in a government shutdown.

Paglia seems much concerned with her legacy. “A writer must always think about being read in the future,” she told an interviewer in 2004. “I’m always thinking how to make what I’m writing relevant not only to contemporary readers but to someone looking at it ten, twenty or thirty years from now.” She might want to consider that her cheerleading for Trump and, sadly, not her early books, is what she might be remembered for.