Canadian researcher cracks 135-year-old ‘unsolvable’ code

A mysterious code written in the late 1800s gripped researchers for nearly a decade. Two scraps of paper tucked in a hidden pocket inside an antique silk dress contained a jumble of words so strange that they flummoxed some of the world’s best cryptographers—experts in coded messages.

“Helena onus lofo us nail each” read one line. “Calgarry Cuba Unguard confute duck fagan egypt” appeared on another. The papers contained 24 lines in total, a historical bit of word salad floating into our modern world entirely without context.

The mystery piqued the interest of an analyst with the University of Manitoba who, in a stroke of investigative genius, managed to untangle the code and link it to a fascinating moment in the early history of weather observations.

MUST SEE: Seven times weather unexpectedly changed the course of history

A random find sparks a yearslong, global interest

Sara Rivers-Cofield is an American archaeologist and curator in Maryland who enjoys collecting historical items in her downtime. She bought a bronze-coloured silk dress while browsing antiques during the holidays in 2013.

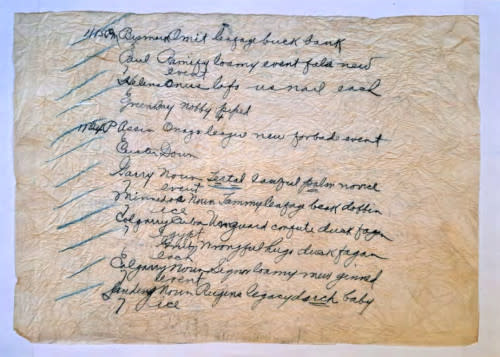

A few months later, Rivers-Cofield wrote about the dress on her blog, including how she found a hidden pocket inside the dress that contained two delicate scraps of paper sporting 24 lines of unusual, seemingly nonsensical words.

The second sheet of the 'silk dress cryptogram.' (Sara Rivers-Cofield/University of Manitoba)

“My first thought was maybe a writing exercise? Or some kind of list,” she wrote in the February 2014 post detailing her exciting find. Rivers-Cofield went on to add: “[...] I'm putting it up here in case there's some decoding prodigy out there looking for a project.”

The post made its way into the orbit of cryptographers around the world who relish the challenge of cracking codes.

University of Manitoba researcher Wayne Chan took on the project and, ten years after Rivers-Cofield stumbled upon the dress, published his stunning discovery in Cryptologia, a scientific journal devoted to cryptology.

A code’s secrets unlocked

Chan’s paper Breaking the Silk Dress cryptogram details the painstaking effort undertaken to decipher two blocks of random words. Were they really just linguistic doodles after all, or something more?

Of all things, the code turned out to have an atmospheric connection.

Back in the late 1800s, there were really only two methods of long-distance communication: mail a letter, or send a telegram. Telephones and radios wouldn’t come into common use for a while yet, so sending a telegram was the only way you could send short messages over long distances in a hurry.

Telegraphy involved operators tapping out electronic messages in Morse code, which were translated and written down for the recipient on the other end.

This tedious process required brevity. Relaying dozens of weather observations from around the U.S. and Canada several times a day would be even more tedious still.

WEATHER HISTORY: Wright brothers telegraphed the U.S. Weather Bureau to plan 1st flight locale

The U.S. Congress mandated the creation of a weather bureau in 1870, the first iteration of today’s National Weather Service. This task fell to the U.S. Army Signal Service, the department responsible for handling information and communications.

Given the department’s experience with sending coded messages via telegraph, the Service developed a dedicated code for transmitting detailed weather observations using just five or six words.

Words, Chan realized, that included those found in lines like “Helena onus lofo us nail each” and “Calgarry Cuba Unguard confute duck fagan egypt.”

How the ‘weather codes’ worked

One could get lost reading all the telegraphic codes from back in the day. There were codes for telegrams as sensitive as military instructions to those as mundane as “our mother arrived late on Wednesday.”

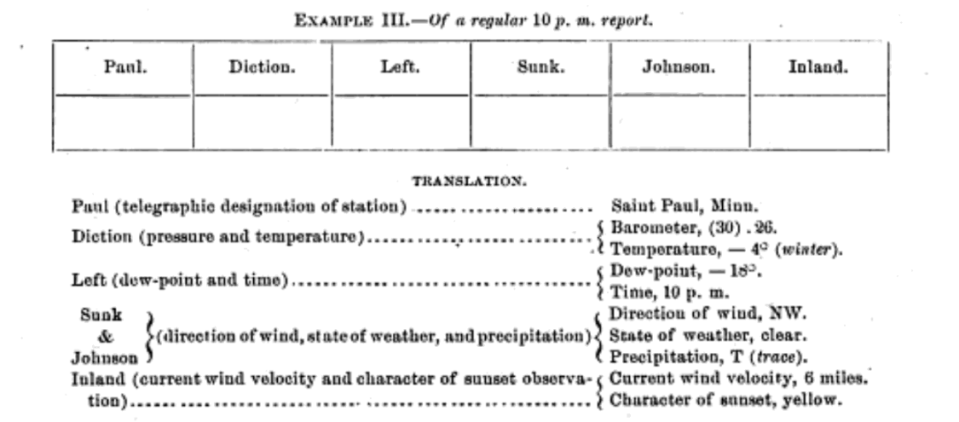

The U.S. Army Signal Service's Weather Code from July 1877—which is freely available online via Google Books—outlines the exceptionally intricate detail involved in crafting each word so that a simple line delivers a graphic outline of weather conditions.

An example of the weather code included in the July 1877 edition of the U.S. Signal Service's telegraphic weather code. (NOAA/Google Books)

Take this observation, for example: “Paul Diction Left Sunk Johnson Inland.” According to the July 1877 handbook:

Paul is short for the observing station in Saint Paul, Minnesota

Diction is code that tells us the barometric pressure is 30.26 inHg and the temperature is 4°F

Left conveys that the dew point temperature is -18°F and the observation time was 10:00 p.m.

Sunk and Johnson together tell us the winds were from the northwest with clear skies and a trace of precipitation that day

Inland relays that wind speeds were 6 mph and the “character of sunset” was yellow.

The pure depth of this code system is utterly fascinating. Each consonant and vowel in each word has its own meaning, so a seasoned veteran could tell the weather just by mentally breaking down each word of the telegram. The codes even took into account factors like longitude, time of day, and seasons.

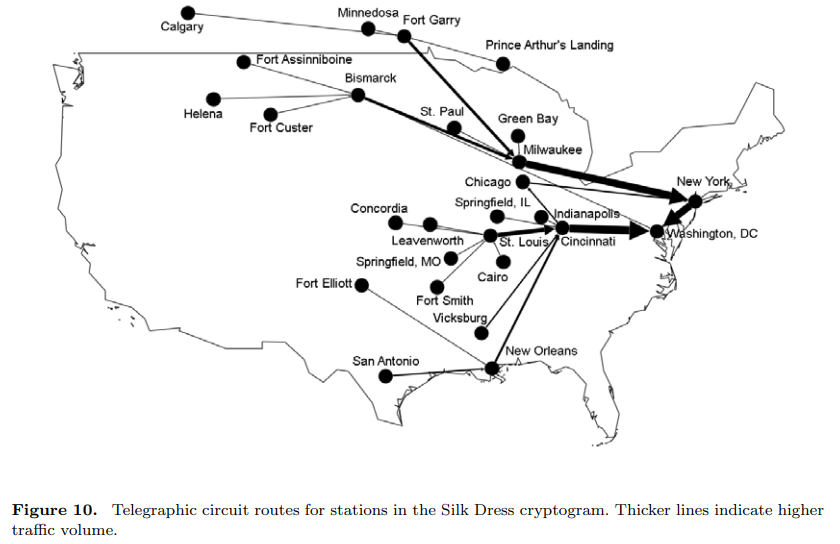

A map of observation stations included in the report, and the circuits the reports travelled to reach Washington, D.C. (University of Manitoba/Wayne Chan)

Chan’s extensive research, which included the work of experts from both NOAA and Environment and Climate Change Canada, narrowed down the weather observations held by the silk dress cryptogram to a single date: May 27, 1888.

The records included observations from Calgary, Winnipeg, and many more stations across the central and eastern U.S.

While a chance find hidden in the pocket of a silk dress brought to life a small glimpse of 19th century meteorology, there are still some unanswered, and likely unanswerable, questions.

Whose dress was this, and why did she have these papers tucked in an intimate pocket? The name “Bennett” sewn into the back proved little help to Chen, though the evidence seems to point to the previous owner working with or around telegrams in Washington, D.C.

These fine details may be lost to history. But her apparent efforts—and those of her contemporary colleagues—paved the way for the instant weather observations and exceptionally accurate forecasts we take for granted today.