How canal conflict, closed Haiti border are igniting racial tensions in Dominican Republic

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The 34-mile river that flows from the Pico de Gallo mountain in the Dominican Republic and runs along northeast Haiti is, geographically speaking, the divider along these two nations. But the division between these two acrimonious neighbors is a lot deeper than the waters of La rivière du Massacre, the Massacre River.

The ongoing conflict between the Dominican Republic and Haiti over the construction of a canal on the Haitian side prompted Dominican President Luis Abinader last month to cancel visas for Haitians and shut down all movement of goods and persons through his nation’s entire land, sea and air border.

Now, the shutdown is shining a light on the long history of racial tensions on the island of Hispaniola, which the two countries share.

Along with the increased Dominican military presence on the more than 220-mile border — where Abinader is also building a wall to keep undocumented Haitian migrants out — there has been an increase in the number of immigration agents on the streets of the Dominican Republic — and in deportations to Haiti. Since the beginning of the year, more than 200,000 Haitians have been expelled, authorities said, and since the canal dispute, more than 100,000 have voluntarily returned.

“People are increasingly afraid,” said Edwin Paraison, a former Minister of Haitians Living Abroad who is a well-known Haitian activist in the Dominican Republic. ”There is a resurfacing of anti-Haitianism.”

That hostility is not just targeted at Haitians but at anyone who has a darker skin tone.

Dominican woman deported to Haiti

Last month, Cristina Martínez Lorenzo, a dark-skinned Dominican woman from the province of San Cristóbal, found herself caught up in the immigration sweep after she was mistaken for a Haitian national, according to her aunt and a local journalist who investigated her case.

“She arrived at the Cambita Hospital with a stomach ache and sat there waiting for the doctor to treat her. The doctor did not treat her. She had a crisis; she began to break down,” Dominga Martínez said about her niece, a mother of two who suffers from mental illness. “The police here in San Cristóbal picked her up and took her to immigration.”

From there, Cristina Martínez was transferred away, leaving her family in the dark about her whereabouts until they received a video of her in an immigration vehicle, the kind used to deport undocumented Haitians. She was in immigration custody for three days, Dominga Martínez said, before “they took her to Haiti” on Sept. 23..

Martínez finally re-emerged in her country 23 days later, wearing different clothes. Her aunt assumes that she had been across the border in the Central Haiti town of Belladère, which borders the Dominican province of Elías Piña. Dominga Martinez said her niece told them that she was in Haiti and had been raped.

Like many Dominicans, Dominga Martínez is reluctant to see her niece’s deportation as an act of racism. Instead, she says, her niece ended up in her predicament because she had no personal documents when police arrived, leading them to assume she was Haitian, “which is normal here.”

But others in the country believe the problem is much deeper, that it is part of the anti-Haitian sentiment resurfacing in the midst of the ongoing diplomatic dispute over the canal’s construction. By late afternoon Monday, the Dominican government had not responded to a series of questions emailed by the Miami Herald.

Last week Abinader, who insists the canal off the Massacre River will divert water from Dominican farmers, reopened the border. But only essential goods, he said, would be allowed to cross and Haitians would remain banned from crossing into his country.

Haiti, which views the Dominican stance as an affront to its sovereignty, has kept its side of the border closed.

Edith Febles, who hosts the daily morning broadcast El Día, The Day, on Dominican local Telesistema 11 and “La Cosa Como Es” — How Things Are — on Teleradio América, was one of the few journalists who reported on Cristina Martínez’s disappearance. In one program, she said the case was “symbolic” of her country’s lack of compassion.

In another, Febles, who has cafe-au-lait complexion, pleaded for Abinader and his cabinet ministers to help locate the missing woman and she asked why no one other than Cristina’s family was looking for her. The journalist insisted the woman was Dominican, as were her parents.

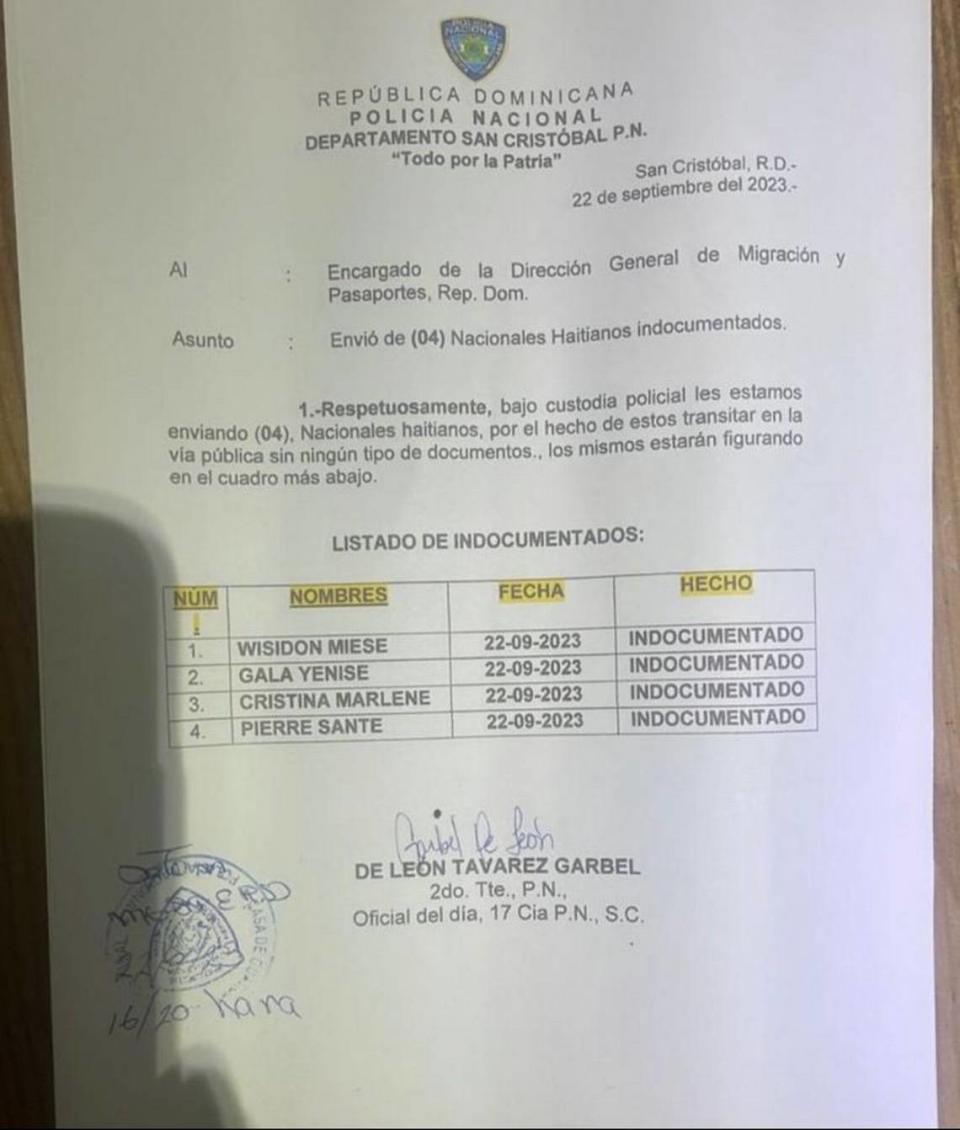

Febles is continuing her investigation into Cristina Martínez’s treatment. During her broadcast, she presented a series of documents, provided by the family, showing how Martínez’s name was changed to make it sound French. A police document, dated Sept. 22 and shared with the Miami Herald, listed her as being among four Haitian nationals. Her name is given as “Christina Marlene.” Her status: “Indocumentada” — undocumented.

“What is fundamental in all of this is the color of the skin, which shows that even... the Black Dominican population is in danger,” said Paraison.

But the fear that anyone who is of a darker hue can be arrested and detained because authorities think they are Haitian isn’t isolated to Black Dominicans. Last November, after the country launched mass deportations of Haitians, the U.S. Embassy in Santo Domingo warned African-American visitors they could be mistaken for being Haitian and be detained and deported to Haiti.

Dominican officials rejected the U.S. criticism and said the travel alert had negatively affected tourism. Testifying before a congressional committee four months later, Secretary of State Antony Blinken defended the warning.

After multiple cases of concerns, he said, “we got to a point where we felt it was important to make sure people could look out for their safety.”

Asked if he thought the Dominican Republic’s government was racist, Blinken replied, “No. We have concerns about the treatment of the Haitian population.”

Seven months later, that treatment remains an issue.

“Anyone who is close to the prototype of the Haitian physical characteristics will deal with the same immigration agency that goes everywhere, every day onto the streets of the Dominican Republic, picking up people without mercy, and frequently violating their human rights,” said Juan Miguel Pérez, a sociologist who was raised in the Dominican Republic and teaches at the University of Santo Domingo. “And that is what happened with this lady.”

Haitian woman raped

Abinader is running for reelection, and some say his campaign against the Haitian canal is the work of advisers who see the issue as a positive in winning voters in a country that in 1912 passed laws restricting the number of Blacks who could settle there and still resent Haiti’s 22-year occupation.

The Dominican Republic does not celebrate its independence from Spain but it does celebrate its freedom from Haiti, which occupied it until 1844 after invading in 1822 and liberating its slaves.

Abinader’s actions have led to several racist acts in his country, critics say. For example, on the first day of the border closure, a transportation union announced that drivers would be prohibited from transporting Haitian passengers. The threat didn’t materialize, but Paraison said Dominican officials’ failure to denounce the plan only added to Haitians’ feeling of uneasiness.

Two weeks later, a Haitian woman in detention at Las Américas International Airport in Santo Domingo, the Dominican capital, reported being raped by an immigration agent in the presence of her 4-year-old son. Dominican authorities later confirmed the agent’s arrest. But more allegations of abuses continued to surface.

Last week, the Dominican Missionaries of Rosario in El Seibo denounced abuses by the General Directorate of Immigration, detailing how immigration agents had knocked down doors and dragged Haitians, some half naked, out of bed at 2 a.m. and violently loaded them onto trucks and transported them to the Haina Detention Center. There, they were beaten and threatened, and had their belongings stolen.

The same day the religious group’s concerns were reported, local media reported that the head of Immigration, Venancio Alcántara, had fired 10 agents and launched an investigation into alleged abuses after human-rights groups complained.

Pérez said many Dominicans live side by side with Haitians and people from the two countries frequently marry each other, so “it’s hard as a sociologist like I am to say the Dominican people are racist.” Instead, he views racism as a structural problem used as a tool by those in power, and propped up by the silence of the country’s liberal intellectuals.

“Historically Haiti has been used by the ruling class in this country as a tool for manipulating public opinion,” Pérez said. “That’s just entertainment to try and distract people from their own problems and from the responsibility of the elite and the problem of the poor Dominican.”

But there is a price.

“These types of things do not help the way in which people relate to one another on the streets,” he said. “It’s also impossible not to have an economic impact.”

Just last week, Dominican egg producers announced they had been forced to declare bankruptcy. Blaming the government, the Association of Poultry Producers of Moca and Licey al Medio said Abinader’s borders shut down left them unable to sell 50 million eggs to Haitians.

“The first problem is economic,” Pérez said. ”The second is the illusion that this country can get rid of the immigrants and transform that workforce composed of immigrants and substitute it with Dominicans.”

A 2017 immigrant survey showed Haitians accounted for 87% of the Dominican’s immigration population, 497,825 people. Another 253,255 were born in the Dominican Republic from at least one Haitian parent.

Despite this, there is a lack of comprehension among Dominicans society of what it means to be an immigrant, Pérez said. While Dominicans abroad, for example, are afforded work permits, medical benefits and legal immigration status and respect for their human rights, Pérez said, “we don’t apply the same rules that we benefit from abroad toward Haitians.”

“Here are people who are working in the fields, who harvest our food, who are building our streets, building our buildings and we renounce them,” he said, adding that the problem is compounded by the attitude of liberals in government.

Case in point, Pérez said, are the politics around Abinader, whose Modern Revolutionary Party emerged from the leftist Dominican Revolutionary Party. The PRD’s one-time leader was José Francisco Peña Gómez, a three-time candidate for president of the Dominican Republic and one of the most prominent Black political figures in Latin America. An outspoken defender of political, social, racial equality and justice, he died in 1998 from cancer at the age of 61.

Both of Peña Gómez’s biological parents were of Haitian descent, and were among those killed when Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo ordered the killing of thousands of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent in 1937, in what became known as the Parsley Massacre. Their bloody corpses were dumped in the Massacre River.

Ironically, were he alive today, Peña Gómez could have well found himself among an estimated 250,000 Dominicans who in 2013 had their citizenship stripped after the Constitutional Court ruled that Dominicans born after 1929 to parents who were not of Dominican ancestry were not entitled to citizenship. Suddenly made stateless, many of these Dominicans currently are still fighting for recognition.

Abinader: No racism in Dominican Republic

Last month, while attending the United Nations General Assembly in New York, Abinader was questioned by a student during a talk at Columbia University about the canal, and the racism and so-called colorism in the Dominican Republic. He staunchly defended his canal stance and said there was no racism in the country.

Eighty-five percent of the population in the Dominican Republic, he said, was of mixed race. When the student insisted there was a race problem, an irate Abinader responded, “That is your opinion, but it is not the real problem we have in the Dominican Republic.”

Since coming into power in 2020, Abinader has adopted an ultra-conservative agenda that has had negative effects on the Black population, particularly Haitians migrants and their descendants, Ana Belique, a Dominican social activist said.

“In the Dominican Republic, there is a reality that exists, it’s racism. But the authorities don’t acknowledge it and they hate it when people talk about it,” she said. “And when you speak about it, you become the person who is in danger, who is targeted.”

That means, she said, the Dominican Republic remains unable to tackle the issue of racism.

“Cristina is not the first Dominican who has been confused with being Haitian and then sent to Haiti,” she said. “But what has made this case even more grave is that she is someone who suffers from mental problems and the authorities did not take this into consideration. It shows how Dominican immigration works.”

Belique, who was born in the Dominican Republic of Haitian descent, is a part of the group “Reconoci.do,” which was formed after the constitutional court’s decision but whose members have long been fighting for recognition of their right to to be recognized as Dominicans.

“Whether you are undocumented or have been documented, once they see that you are darker than them or you don’t look like what they have in their minds a Dominican should look like, they can grab you, arrest you and deport you to Haiti,” Belique said. “That is the reality we live day to day, especially among those who live in communities where there are a lot of Haitians.”

Belique noted that in recent years, pregnant Haitian women in the Dominican Republic have been taken out of hospitals, detained and sent to Haiti. Even the “voluntary” deportations that the government has been touting, she said, are actually people forced to leave under duress.

“They enter our homes at 2 a.m., 3 a.m. in the morning,” Belique said. “For Black people, for Haitians, for individuals who are Dominicans, but immigration think they are Haitian, there is nowhere that is safe.”