'Canal killings' Part 1: Brutal slayings end the lives of 2 young Phoenix women

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

'Canal killings' series:

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 (coming soon) | Part 4 (coming soon) | Part 5 (coming soon)

Nov. 8, 1992, a little after 7 p.m.

Angela Brosso grabbed her Sony Walkman and headphones and told her boyfriend, Joe Krakowiecki, that she was headed out for a bike ride.

It was a Sunday, and "Star Trek" had just started playing on the TV in their north Phoenix apartment. Joe was busy, baking a cake to celebrate Angela's 22nd birthday the next day.

Go for it, he told her.

She was wearing purple shorts and a purple shirt, under a gray sweatshirt that Angela — Angie, Joe called her — had taken to wearing inside out. White tennis shoes and socks. She had rings on her fingers, earrings in her ears, a wristwatch.

She got her music player to listen to some tunes as she cycled. And then she left.

Joe figured she'd be home in 45 minutes or so. They were casual watchers of "Star Trek," but the main event was "In Living Color," the comedy sketch show that came on right after, at 8 p.m.

With no VCR, and streaming services more than a decade away, it was appointment television, only missed if one or the other was out of town. It was how they ended pretty much every week.

Angela and Joe had met studying in New Jersey, forced apart by degree requirements that sent her to California and him to Arizona, before they reunited in Phoenix in June 1992. That's when they moved into the Woodstone Apartments by Cactus Road and Interstate 17. Just east of the enormous block lay a small field, and beyond it, an asphalt bicycle path that ran along a diversion canal.

Angela sometimes cycled alone, but more often she and Joe went together, a hobby they had picked up in earnest after she moved to Phoenix. They would ride the canal in the evenings, either a 45-minute or 1.5 hour loop from their house, on twin 21-speed Diamondback Topanga mountain bikes. Angela's was purple.

As she took it out on the evening of Nov. 8, Joe didn't give her plan a second thought. He did not, at that point in his life, have reason to be cautious.

They had spent the day together, picking up their bikes from the shop, where they had taken them for a tune-up ahead of all the winter cycling they had planned. Then they had eaten at a Fridays restaurant just south of the Woodstone before heading home.

It had been a low-key Sunday, one Joe would only remember three decades later because of what happened.

At 8 p.m., right on schedule, the "Star Trek" credits rolled. The "In Living Color" theme played.

But Angela hadn’t come home.

A body on the berm

Nov. 9, 1992, 9:16 a.m.

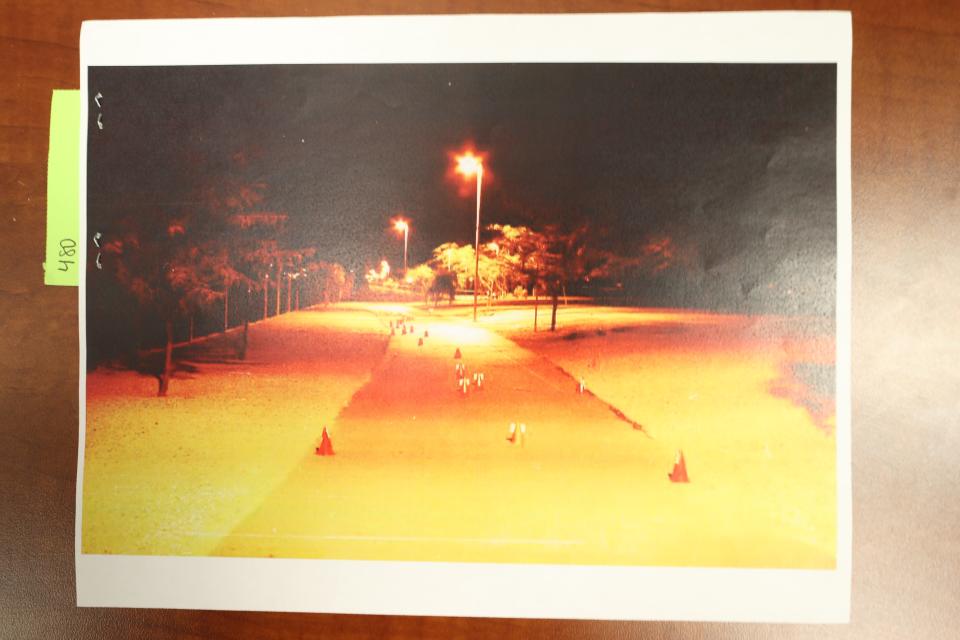

From the path, all that was visible were white tennis shoes, poking up above the berm. The police officers cycling along the canal hadn't seen them yet.

The morning sun illuminated the first traces of what lay up there. The once-bright red droplets, now muted on the pavement, spanned some 150 feet.

Then the trail veered off the cycleway, perpendicular through the dirt equestrian path and up to the field just east of the Woodstone Apartments. A thick bloody drag trail stained the earth, pieces of what looked like cut purple clothing left in its wake.

Before he could cross over the blood, Robert Wamsley, one of the cycling cops, stopped pedaling. His partner braked next to him on the dirt.

They had set off from a fire station on Cactus Road about 15 minutes earlier, riding south along the diversion canal as they looked for a missing person, a young woman who had gone out cycling and never returned.

As they followed the trail with their eyes, they saw the shoes.

Wamsley approached cautiously. At first, he thought it was a mannequin, some kind of sick practical joke. He gave it a berth of about 10 feet as he inched his eyes upward, waiting to arrive at the head.

It was missing.

The victim had been stabbed in the back, a fatal strike to her left shoulder so forceful, a medical examiner would later say, that it pierced her lung and aorta. Investigators would conclude it was the first wound, the one from which blood had spilled out and stained the path. The one that killed her.

It wasn't the last.

Nobody knows how long the killer spent with the body, and he won't say. He carried out his sick fantasies with a knife, sexually assaulting her as she lay limp on the ground, then cutting off her head.

Police would identify her as Angela Brosso.

Three decades later, attorneys would take care not to accidentally expose court staff to the crime scene photographs. Retired Phoenix police Sgt. Troy Hillman said it was the worst thing he had seen one human do to another. "It was evil," he said. "At the highest level."

The medical examiners who would later comb Angela's body for clues would conclude, in the smallest of small mercies, that most of it likely occurred once she was already dead.

The killer won't say what he did with Angela's bike. Or her Walkman.

Or what happened to her head in the 11 days before it was discovered by a fisherman, 1.5 miles away from her body, caught on a grate in the Arizona Canal where the water flows by theme park Castles N' Coasters and the now-shuttered Metrocenter mall.

Remembered for her life: Testimony: Victim in 'canal killings' was set for a new work assignment when she vanished

Wamsley, now certain he was looking at a real body, radioed his supervisor.

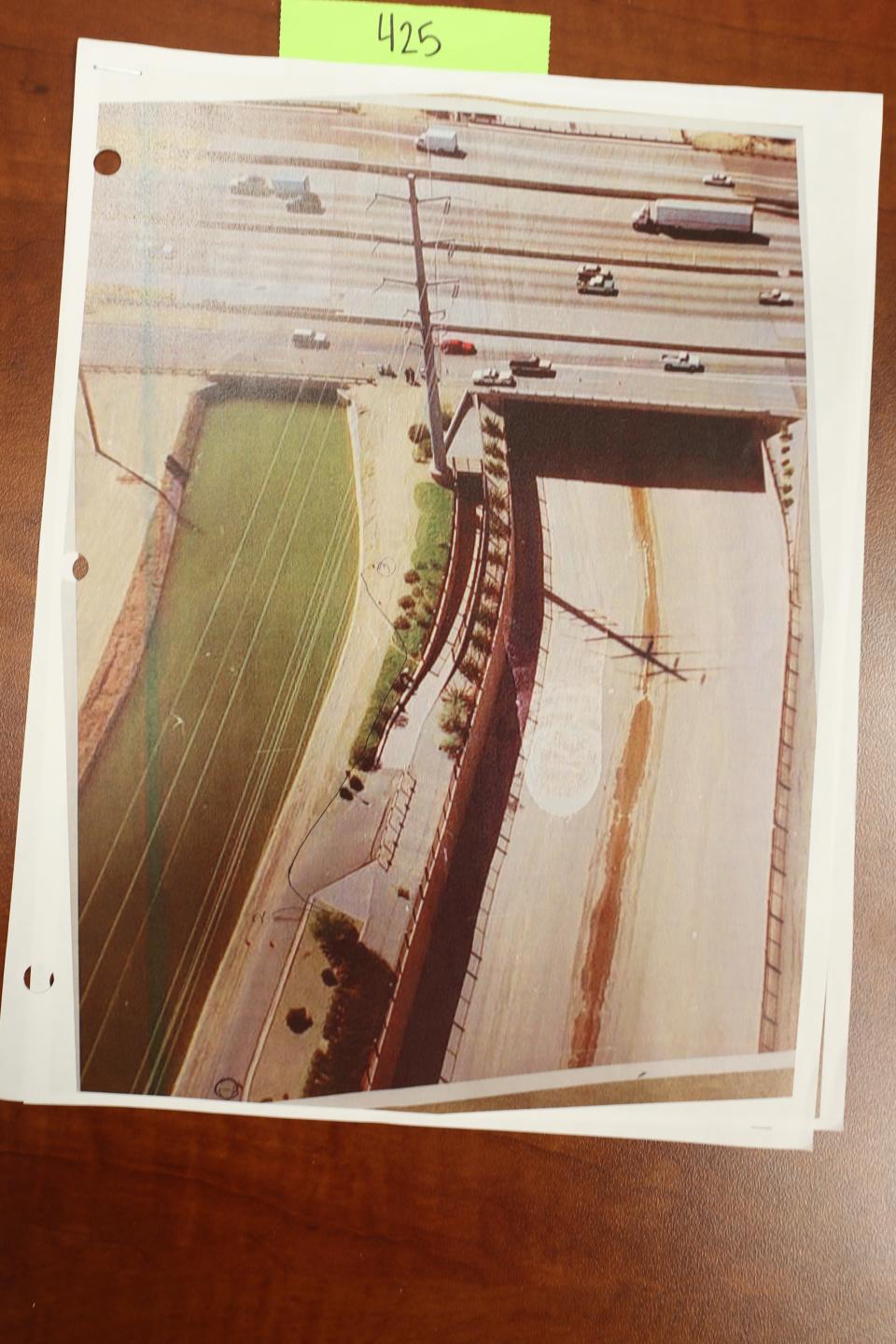

They arrived car by car, officers and detectives to secure and process the scene, a mobile command van to run the operation. Detective Mike Meislish, the assigned scene investigator, canvassed the scene from a helicopter, an officer snapping aerial photographs beside him.

These were the first moments in an investigation that would become one of Arizona's most notorious cold cases.

As the scene crawled with activity, a man pulled up along Cactus Road.

His name was Lynn Jacobs, and he had recently moved out of the Woodstone Apartments. He had no idea what was going on. But irrepressibly curious — and, due to the state car he was driving for his Department of Transportation job, able to move in closer than other people — he sat there for 15 minutes and watched the chaos unfold.

It was a scene that would stay with Jacobs for a very long time. Thirty years later, when he was 70 and long-retired, it would compel him to spend eight months of his life in a downtown Phoenix courtroom, watching the story wind to a close.

Police had been at Angela and Joe's apartment since the early hours, quizzing a frantic Joe about what had happened. He tried to help the best he could.

As he spoke to them, the TV was playing in the background. On the news, from a helicopter's vantage point, he saw a body lying in the field next to the Woodstone.

At some point, the phone rang. Angela's mother, Linda, was calling to wish her daughter a happy birthday.

'I'll see you in a little while'

Sept. 21, 1993, a little after 7 p.m.

Melanie Bernas was sitting on the couch, dressed in her pajamas, an oversized white T-shirt and shorts.

She had stayed home sick from school that day, missing early classes of her junior year at Arcadia High. Her mom, Marlene, was getting ready to go out for dinner.

Melanie asked how long she'd be gone. About two hours, Marlene said. She kissed Melanie goodbye, told her she loved her.

"I'll see you in a little while."

Melanie had turned 17 the week before, inching toward adulthood, but still the baby of the family. Her older siblings, in their 20s, had flown the coop, leaving just Melanie — and Hershey the dog — at home with Marlene.

The Arizona Canal wound through their Arcadia neighborhood. Marlene would walk along the water with the dogs, and in the daytime ― Melanie wasn't allowed to go at night ― the teen would ride the bike path with her friends. Sometimes, they ventured as far as Metrocenter, though her mom didn't know it at the time.

A mother remembers: 'Canal killings': At Miller trial, mother recalls the last night she saw her daughter alive

When Marlene got home around two and a half hours later, her daughter wasn't there.

It wasn't like Melanie. She always abided by her curfew, which was 9 p.m. on a school night.

Marlene's first thought was that Melanie might be at her dad's house. But when she called, he said he hadn't seen her. She rang a friend, who hadn't seen Melanie either.

There was something else missing too, something Marlene didn't realize until she went into the utility room where she and Melanie kept their bikes.

Melanie's green SPC Hardrock Sport mountain bike was gone.

Blood on the bike path

Sept. 22, 1993, about 8 a.m.

Charlotte Pottle and her sister strapped their toddlers to the back of their bikes, ready to ride the Arizona Canal.

They set off on the same route they always did, taking the Peoria sidewalks until they hit the canal at 51st Street and Cactus Road. From there, it was a continuous path, with underpasses to dodge the traffic grid, all the way to Rose Mofford Sports Complex just past Interstate 17.

One of the best parts ― for the kids, anyway ― came just before they reached the park, when Metrocenter and Castles N' Coasters rose up to the left and they descended under the freeway.

Like they did every morning, Pottle and her sister whizzed through the underpass, making noise as they went, the toddlers loving it while their moms cycled fast to make it up the steep hill on the other side ― and, in the way sisters do, try to beat the other.

As Pottle flew out of the tunnel, still trying to gain momentum, she rode through a pool of liquid on the path.

She thought she recognized what it was, but the thought was macabre. She kept pedaling, certain she was wrong.

It's just the angle of the sun, she told herself. It's my glasses. I'm just making things up.

But a feeling of unease lingered. As soon as they got to the park, Pottle had an urge to get out of there that she couldn't explain. They left before the kids had a chance to swing.

A few minutes later, as they returned to the pool on the asphalt, Pottle stopped riding, dismounted, and asked her sister to hold her bike to keep her little girl upright.

Then she knelt down and took a closer look. Now she was sure.

It was blood.

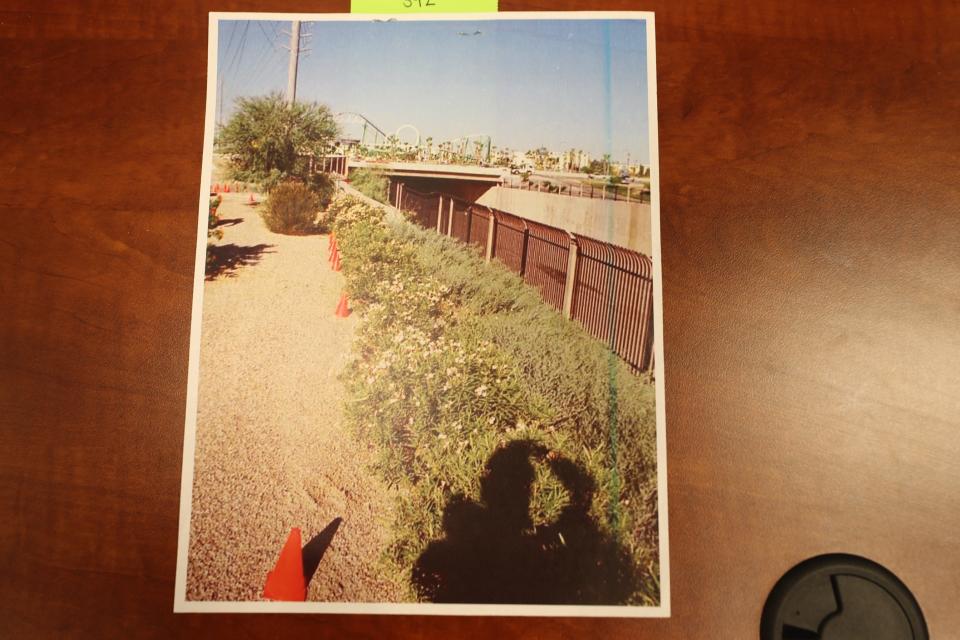

Then she noticed the drag marks, a trail of blood and disturbed gravel that seemed to run toward an area by the path with trees and bushes and then across to the canal.

Pottle followed the trail, over to the brush, and then to the water's edge, where she stopped herself from looking down, wary of what she might see.

Her mind drifted to the head that had been found in the canal 10 months earlier and not far from here, just on the other side of the freeway.

She looked cautiously, first to the right and then to the left, slowly running her eyes back along the waterline, stopping before she reached the area directly beneath her. Nothing caught her attention.

She looked straight down. The trail of blood continued over the edge of the canal, into the water.

She couldn't see anything else.

'Immeasurable' pain: Family of 'canal killings' victims describe impact as judge mulls penalty

A second victim

Sept. 22, 1993, about 11:30 a.m.

Meislish bypassed traffic cones and crime scene tape as he arrived at the scene, walking over to where divers were slowly removing a body from the water, one that would later be identified as Melanie Bernas.

Ten months earlier, the detective had stood just 360 feet away as Angela's head was recovered from the same canal, on the other side of the freeway.

Melanie had drifted a short distance after being dumped in the water, stopping when her body tangled in some brush.

The divers had zipped her into a body bag to preserve all they could for investigators and had moved her to a ramp, where Meislish helped pull her up onto the bank.

When he unzipped the bag, he saw she was dressed in a turquoise bodysuit, a distinctive item of clothing that, Marlene would later tell police, did not belong to Melanie.

Other than that, she wore just her socks and sneakers, same as Angela.

Melanie had also been stabbed in the back, the wound nearly identical to the one inflicted on Angela 10 months before. She, too, had been mutilated, though in different ways, and sexually assaulted, most likely after her death.

As police searched the scene, they found under a bush the cut sleeve of a green T-shirt and a piece of wire from the headphones Melanie typically wore with her Sony Walkman. As the police search expanded, they would find more of her clothes in a nearby dumpster.

They would never find her bike. Nor her Walkman.

And for 22 years, the killings would remain unsolved.

Part 2, coming Tuesday, Aug. 29, to azcentral.com: 20 years later, Bryan Patrick Miller emerges as top suspect.

'Canal killings' series:

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 (coming soon) | Part 4 (coming soon) | Part 5 (coming soon)

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona 'canal killings': Brutal slayings end 2 young women's lives