'Canal killings' Part 2: After 20 years, Bryan Patrick Miller emerges as top suspect

'Canal killings' series:

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 (coming soon) | Part 5 (coming soon)

Part 1: Brutal slayings end the lives of 2 young Phoenix women

Jan. 2, 2015, about 3:45 p.m.

Bryan Patrick Miller arrived at the Chili's Grill & Bar by Metrocenter with his 15-year-old daughter in tow.

He was 42, an Amazon employee who frequently struggled to make rent on the single-family home he leased at the foot of North Mountain. He lived there with his daughter, whom he cared for as a single father.

Miller was meeting a man who approached him a few days earlier, on New Year's Eve, in the parking lot at work. He spent his breaks there, parked in a spot that looked out over the back of a nearby warehouse.

The man was Clark Schwartzkopf, but that's not the name he gave Miller. He said there had been thefts at the warehouse and he was looking for people to pick up surveillance shifts.

Was Miller interested in keeping an eye out for anything suspicious? He'd be paid for his time.

Sure, Miller said.

They arranged to meet at the Chili's for Miller to fill out an application form.

Schwartzkopf hadn't expected him to bring his daughter, but the meeting proceeded without incident. They ordered, ate, meandered through conversation topics: Miller's family, work, how his daughter was doing at school.

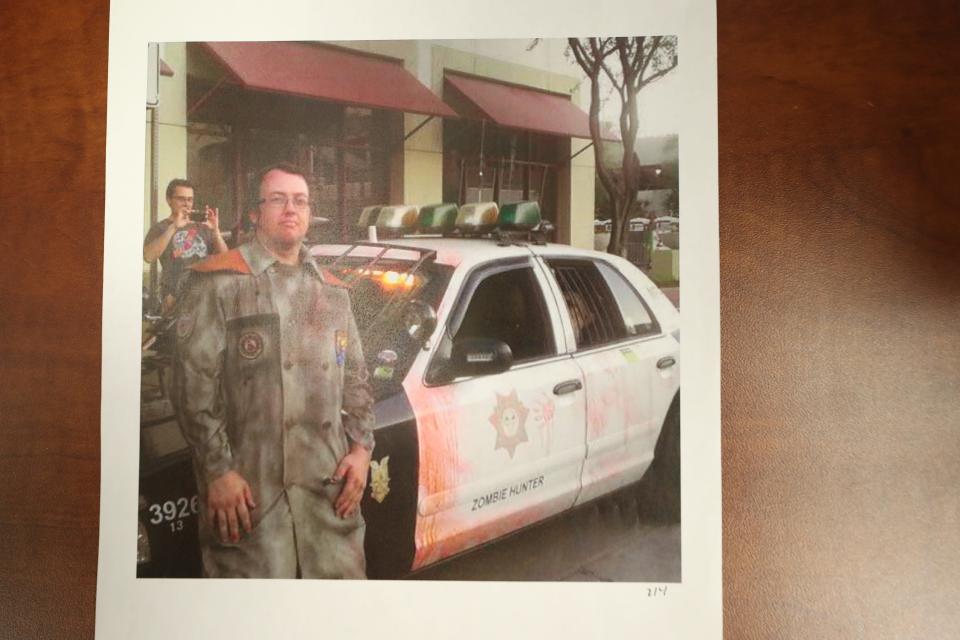

Miller talked about his hobbies, which he pursued in ways some might see as obsessive. He filled Schwartzkopf in on Steampunk, an aesthetic subculture that blends futurism with 19th century technology. Miller was active in the Phoenix scene.

Miller also talked about cars, a passion that had made him famous in the area's small but thriving cosplay community.

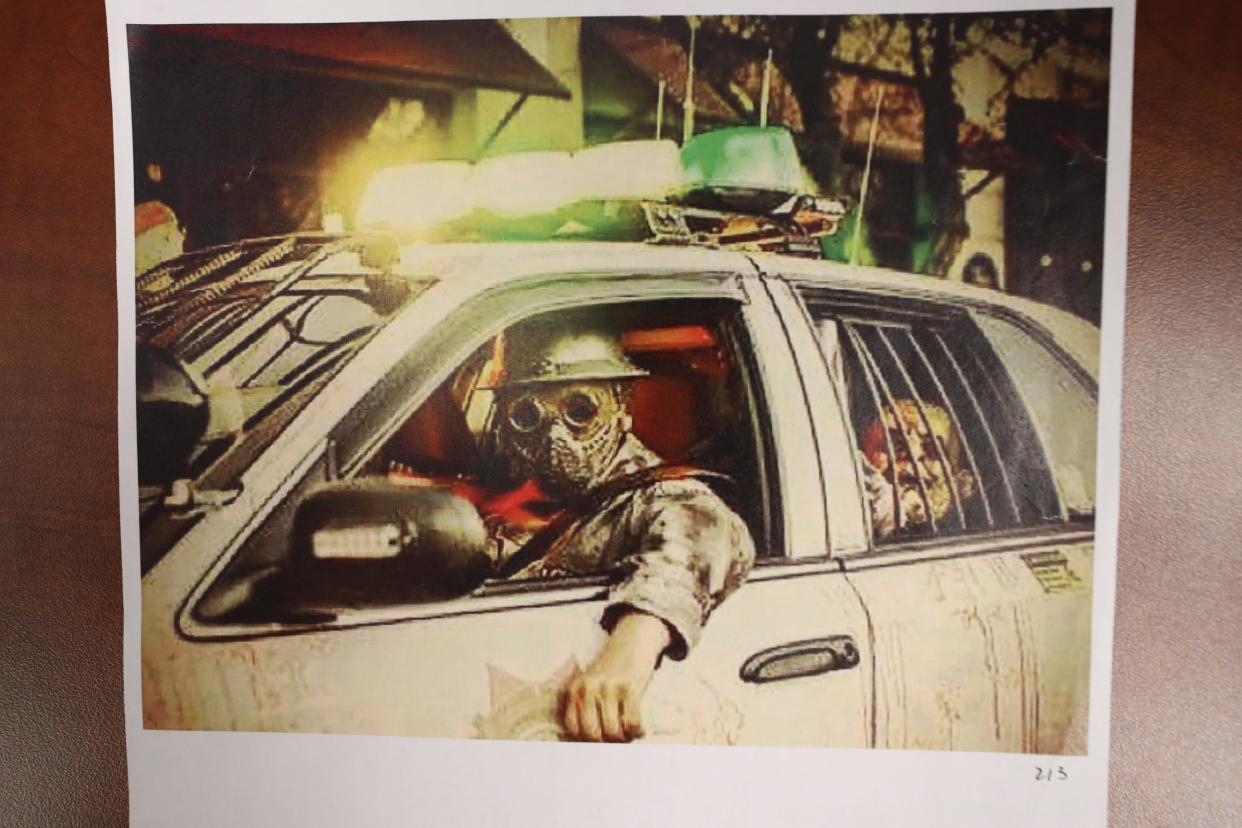

He drove a fake police car, done up with green and yellow lights on the roof and the words "Zombie Hunter" ― a self-styled costuming identity of Miller's ― emblazoned in thick letters on the trunk. The car was a fixture at Comic-Con and other fandom events, where people, sometimes even police officers, would pose with Miller and his car and admire the work he had done on it.

In 2014, Miller had written on Facebook that building the "completely insane" vehicle had made him "a little less invisible" to the world.

Role-playing: 'Canal killings': Judge hears about Bryan Miller's 'Zombie Hunter' persona

After about an hour, Schwartzkopf walked the father and daughter out to the car.

Phoenix police Detective Dominick Roestenberg had arrived at the Chili's before any of them, about 3 p.m., and introduced himself to the manager.

We're investigating a violent crime, he told her. Will you assist?

Roestenberg was among the investigators pursuing the man who had killed two young women more than two decades earlier, murders known as the canal killings.

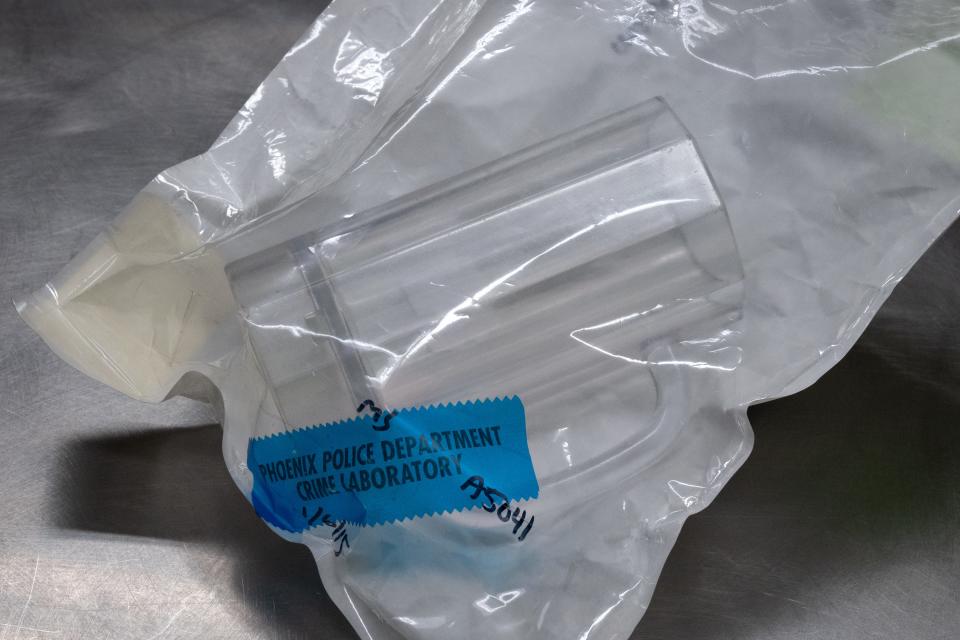

The manager, the daughter of a retired police officer, was happy to help. She took Roestenberg through to the kitchen, where he ran plates, cutlery and mugs through the industrial dishwasher to sterilize them. He locked them in her office, and she retained the key.

And then he sat down in the restaurant with another detective, as if they were normal diners, enjoying a normal lunch.

At a different table sat more undercover officers, including Sgt. Troy Hillman, who led the cold case team. As Hillman attempted to nonchalantly talk and eat, his heart was pounding.

If they were right about Miller, the consequences were enormous.

The operation had already not gone to plan. They hadn't anticipated Miller turning up with his daughter. But the team stayed the course.

They had been watching Miller for days in the hope he would discard something from which they could scavenge his DNA. So far, their efforts had come to nothing.

But that day, Miller left a trace behind.

No new clues: 'Canal killings': Bryan Miller speaks at last, but offers no apologies

As the trio left the restaurant, Roestenberg kept his gaze focused on the plates, mugs and cutlery that remained on the table.

It was imperative he not break eye contact, not until police could bag as evidence the clear plastic Chili's mug Miller had sipped from.

Who is Bryan Patrick Miller?

1972 – 2015

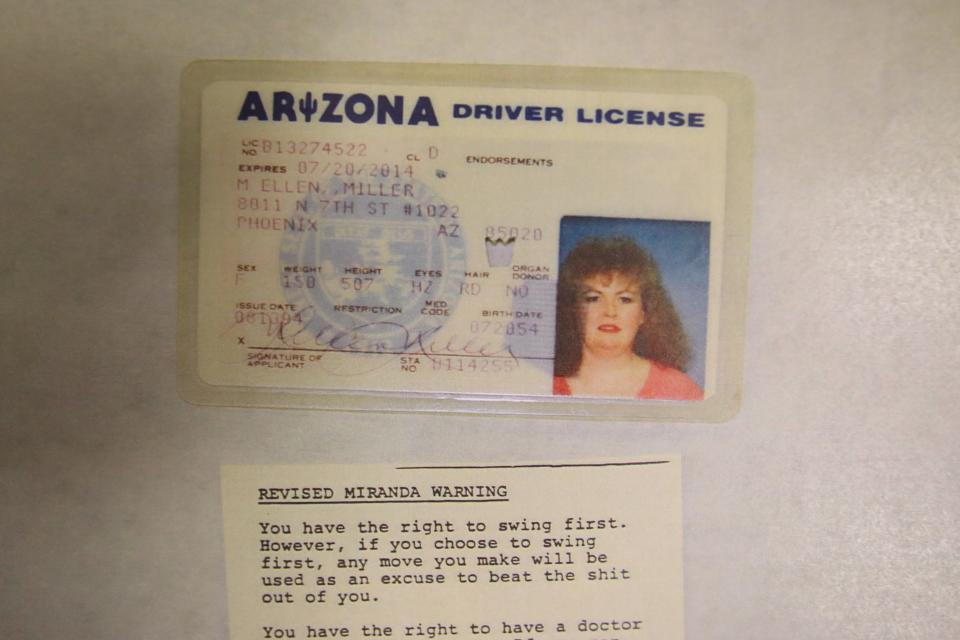

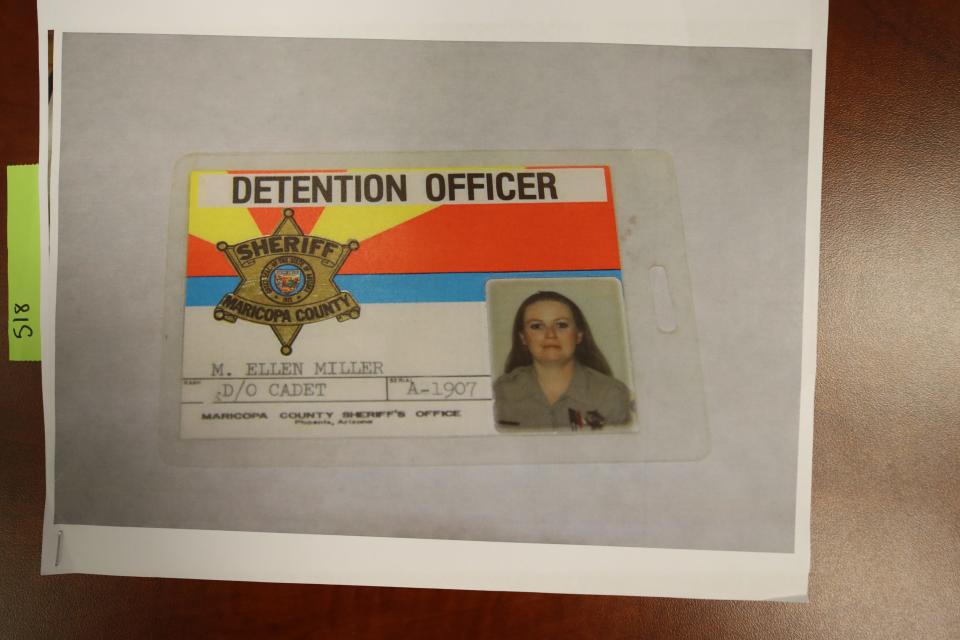

Bryan Patrick Miller was born on Oct. 24, 1972, to his 18-year-old mother, Martha Ellen James, and father, Lester Paul Miller.

The young Michigan couple, who both went by their middle names, had married after finding out about the unplanned pregnancy. After living with Paul's parents for a while, they moved to Hawaii, where he was stationed in the military.

When Miller was 5, on Dec. 15, 1977, his father was killed in a motorcycle accident.

That's when his memories of being abused by Ellen begin.

Decades after knowing her, people remember Ellen as angry. Explosive. Two-faced. A former neighbor would put it this way, under oath: "She was a bitch."

Chronic trauma cited: 'Canal killer' trial: Miller 'walled off' experiences of childhood abuse, expert says

The mother and son lived in greater Kāneʻohe, a short drive from Honolulu, in a neighborhood where kids often played together in the street. People who knew Miller back then remember him as shy, introverted, cowering in the presence of his intimidating and unpredictable mother. An unimpressive Little Leaguer who was petrified of the ball.

In 1983, 10-year-old Miller flew to Phoenix to stay with his aunt and grandparents for what he was told was a summer vacation. It wasn't until he got to Arizona that he found out it was a permanent move, from Oahu to the desert Southwest.

Ellen followed soon after. As Miller tells it, the abuse that had started in Hawaii grew worse. The incidents of abuse he described, and some that others witnessed, ranged from physical to emotional to what would be, contentiously, described as sexual abuse. In court testimony, a forensic psychologist would say Ellen had exposed Miller to things and crossed boundaries in a way that led him to develop a disturbed sexuality, in which violence and intimacy were entwined.

Years after the fact, people who knew Miller as a child would recall witnessing moments that troubled them, left them thinking something was seriously wrong in the dynamic between mother and son.

Gail Wood, a Welsh cousin who visited Arizona three times in the 1980s, said Miller was a quiet boy, in his own bubble, while his mother was controlling, a "strictarian" who could be lovely one second and snap the next.

"I think Ellen had a split personality," she would later say in testimony.

She recalled a visit where a teenage Miller got home from school, only for Ellen to start berating him over some missing cookies. But her accusation wasn't that he had simply eaten them, Wood said. It was that he had taken them to school to trade for sex.

Wood and her mother watched, dumbfounded, as Miller denied the charge, saying "No, no, no," eventually growing so distressed that he crouched into a ball and began to hit his head against the wall.

Ellen, unmoved, told him, "I'm going to get you institutionalized," Wood said. "He was sobbing, and he said, 'Please, please, please phone, get them to take me away, because I'd rather be anywhere than be here with you.'"

Miller spent some time in special education classes, designated as having a speech and language disability and as being emotionally disabled. In adolescence, he had some moderate brushes with trouble ― setting a fire in a trash can at school at age 11, minor shoplifting ― but his issues escalated as he reached his mid-teens.

He spent Christmas 1987 in an inpatient mental health facility, taken there after running away from home for a week at age 15. When he transitioned into Arizona Youth for Change, an outpatient program for troubled youth, Miller, along with Ellen, was required to attend weekly family therapy.

Thirty-five years later, their therapist, Cynthia Elliott, said one session had stayed with her. Ellen, whom she recalled as angry, vulgar and disinterested, seemed to be particularly angry at her son. When Elliott asked why, Ellen explained that she had a Barbie doll collection, a kind of wall display.

OK, Elliott said. So what happened?

Miller had taken something sharp, maybe a knife, Ellen said, and cut a vagina into every single doll in her collection.

"I remember at the time thinking, ‘This is not something I’ve read about in any textbook, how to respond to that,’" Elliott said. She felt Miller was more disturbed than the other kids in the program.

During his time in AYC, he was charged with criminal damage ― he threw a radio and tore a chalkboard off the wall before bolting to a nearby bus stop ― and was sent to juvenile detention at the Adobe Mountain School, where he stayed until March 1989, when he was released on parole.

He would soon commit another, much more serious, crime.

"Which is sort of where this all started, isn't it?" a prosecutor would say about it, decades later.

A stabbing at the mall

May 17, 1989, about 8:15 a.m.

Celeste got off the bus at Paradise Valley Mall and set off across the parking lot, on the way to her shift at the Mervyn's department store.

It was bright, sunny, the city hurtling toward summer. As she walked, Celeste noticed people lining up, perhaps for concert tickets, outside the mall. A yard worker doing some maintenance.

And a boy walking behind her, some distance away.

He was a teenager, younger than Celeste, who was 24. She recognized him but did not know him. He had been on the bus when she boarded and disembarked at the same stop.

She kept walking.

All of a sudden came a blow to her back. Someone ran by her, fast. The boy from the bus. In her shock, Celeste thought he had punched her.

But when she reached around to her right shoulder, she felt something wet. As she pulled back her hand, her fingers were red.

She began to scream.

Celeste was in the ambulance when police brought over a teenage boy to ask if he was the one who stabbed her. He was wearing different clothes, Celeste said, but she still recognized him.

She was taken to a hospital for a tetanus shot and stitches. A scar would serve as a permanent reminder.

Celeste would later learn the name of the boy.

Bryan Patrick Miller.

After stabbing her and fleeing, he tossed the knife and changed his clothes. When first detained by police, he denied it was him.

Over the years, Miller would tell different people different things about why he had stabbed Celeste. To see what it felt like. Because she resembled his mother. He hadn't felt in control of his own body, as if he were watching his computer screen while someone else was moving the mouse.

He admitted to attempted murder and went straight back to Adobe, where he stayed until July 1990, and then a youth halfway house, which he was due to leave when he turned 18.

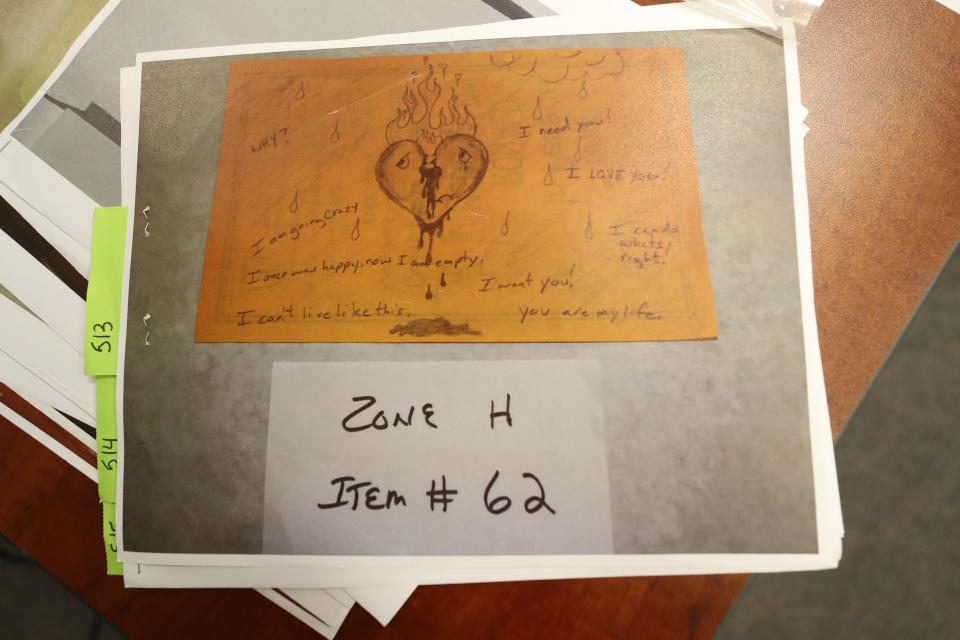

On her son's birthday, Ellen gave police a document. Her son had written it, she told them, and it concerned her.

It was handwritten, the words "Plan (videotaped)" scrawled at the top. The list that followed was detailed, a 24-step guide to kidnapping, raping, torturing and killing a teenage girl. The final steps described slicing open her belly, pulling out her organs, cooking her flesh and keeping her head to look at later.

There was an equipment list and a detailed description ― including name, age and measurements ― of the intended victim. Police checked it out at the time, a detective would later testify, but found nobody of that name.

Miller would later say he recognized his own handwriting, but he didn't remember writing it.

It would linger in his police file for decades, eventually catching the eye of Troy Hillman as he hunted for a suspect in the long-cold canal murders.

In court, they would call it The Plan.

Ellen was unwilling to let Miller return to her after he left the halfway house. He was taken in by the Paradise Valley Mennonite Church and lived in a rent-free apartment on the proviso that he work, either in a paid role or volunteer position, and receive counseling from the pastor about personal hygiene and basic life skills. In May 1992, he was baptized.

Later that year, Miller was working at St. Vincent de Paul when he got to know a co-worker named Randy McGlade.

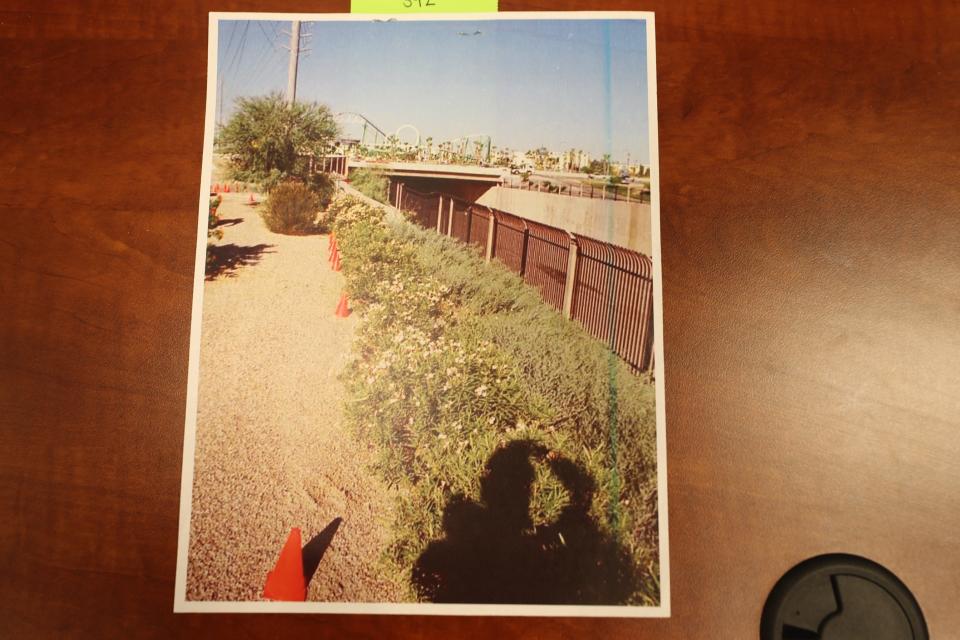

They became friendly, and then friends. By the end of summer 1993, Miller had moved into Randy's place, by Bethany Home Road and Seventh Street. The two men lived together, worked together, and would hang out together too, going to concerts, or the church where Randy worked as a musician, or cycling along the Arizona Canal.

In September 1993, Randy saw a story in the news about a teenage girl who had been murdered as she cycled along the canal near Metrocenter, west of where they lived.

He made a joking comment to Miller: Hey, weren't you out riding the canal that night?

I was riding on the east side, Miller said.

A few months later, a picture of a turquoise bodysuit in The Arizona Republic would jog Randy's memory, remind him of something he had spotted among his roommate's things. He would mention it to someone else. That person would call in a tip to the police in 1994.

It would go in Miller's file, alongside The Plan. Nothing would come of the tip in the years that followed.

In November 1996, Miller met a woman named Amy, a volunteer at St. Vincent de Paul.

She was 19 and had never dated before, a sheltered rule-follower who was raised on daily prayer and Bible study by her devout grandmother. She had dreamed of becoming a teacher, enlisting in the Air Force as a way to afford tuition. But she missed home so badly after two weeks of basic training that she begged for early release.

For their first date, Miller took her to Castles N' Coasters.

Not two months later, on New Year's Eve 1996, he asked her to marry him, and she said yes. That same night, they shared their first kiss.

That Miller was religious had been important to Amy, but she said God seemed to fade as their relationship progressed. Miller scheduled things at the same time as church, meaning they couldn't go, and, as Amy would tell, persisted until they had sex before marriage. They wed in haste and Amy's grandmother kicked her out of the house.

In 1998, the couple moved to Washington state and lived with Ellen, who had promised she could secure a more lucrative job for Miller. The gig never materialized. Money was tight. Amy got pregnant. They moved into their own place. Money got tighter.

In 2002, for the second time in his life, Miller was arrested and accused of stabbing a woman. Amy found out, from her husband's lawyers, that his stint in juvenile detention — which she knew about, but thought was for something minor — had been for attempted murder.

He waited eight months in custody for the trial, which was a he-said, she-said affair. He said she had produced a knife and tried to rob him after he let her into his workplace to use the phone. She said he had stabbed her unprovoked.

The jury sided with Miller. He was acquitted and released.

During his time in jail, he wrote explicit letters to Amy, who was struggling to provide for their toddler alone. In the letters, he described acts of sexual sadism he wanted to perform on her, involving knives and needles.

After his release, Amy said, they began to incorporate BDSM into their sex life. She went along, but did not enjoy it. At first, she acquiesced because she believed it was her role as a wife, she would say. Later, it was because she had grown scared of her husband.

The Washington experiment ended less than a year later, when the Millers moved back to Phoenix. They divorced in 2006 and co-parented for a while before Miller won full custody.

In the years that followed, Miller raised his daughter, worked various jobs, got involved in Steampunk and cosplay and the Renaissance Fair. He dated around a little. In 2010, his mother died.

And then in January 2015, he walked into the north Phoenix Chili's.

Part 3, coming Wednesday, Aug. 30, to azcentral.com: DNA breakthrough helps police catch a killer.

'Canal killings' series:

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 (coming soon) | Part 5 (coming soon)

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona 'canal killings': Suspect Bryan Miller emerges 20 years later