'Canal killings' Part 5: Miller gets ultimate punishment; families, friends mourn Phoenix victims

'Canal killings' series:

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

Part 4: 30 years later, Bryan Patrick Miller stands trial

For 54 days, spread out across six months, lawyers presented evidence and questioned witnesses in the case of Arizona vs. Bryan Patrick Miller.

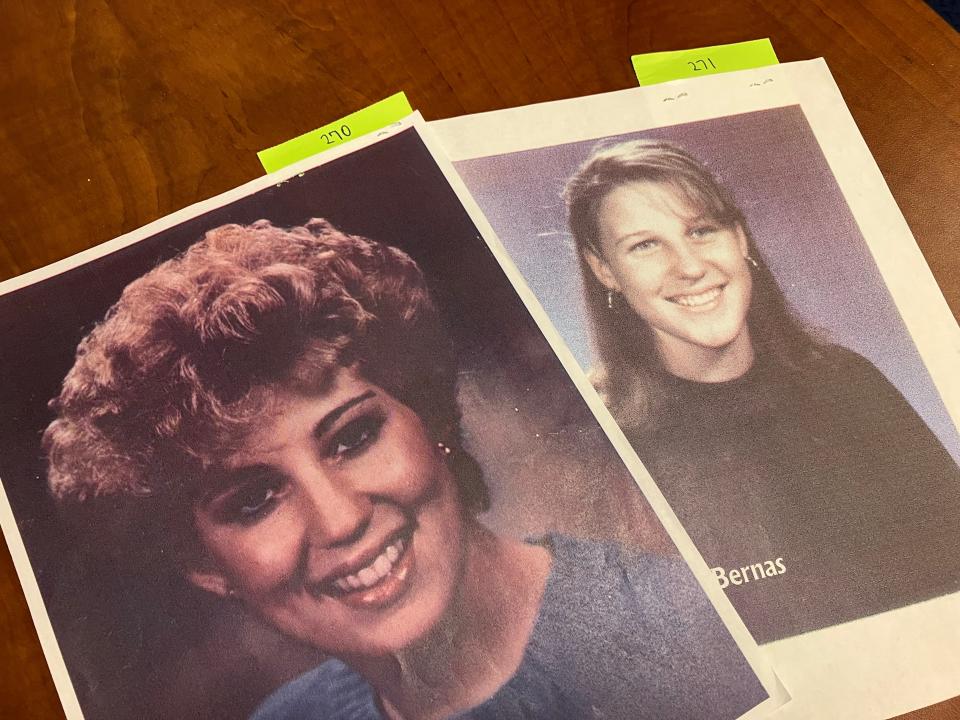

The capital murder case dated back to the early 1990s, when Angela Brosso and Melanie Bernas were killed as they cycled along Phoenix canals. The brutal murders shocked the city, but their killer evaded capture for years.

A DNA breakthrough led to Miller's eventual arrest. But at trial, the science was a footnote. He pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, so the evidence centered on his experiences, the different disorders experts believed he had, and his state of mind 30 years ago.

As the trial hummed on, everyone had grown used to the empty jurors' chairs. But as closing arguments approached in early April, they loomed again. They were a reminder that Judge Suzanne Cohen presided over a bench trial. She would deliver a verdict and she would impose a sentence.

On the morning of April 5, prosecutor Elizabeth Reamer handed the judge two photographs.

"I think humans want to believe that only someone completely insane would do this," she said, as the judge studied them, unflinching. "But your honor, this entire trial proves that that's not true."

Miller may have some mental health concerns, some diagnoses, prosecutors said. He very likely had a bad childhood. But nothing that came close to explaining what he did to Angela and Melanie. His attorneys had spent months presenting an insanity defense, they said. It was nonsense. Don't believe it. Use common sense. Look at the evidence.

"Why would you move Angela? Why would you move Melanie? If you think what you’re doing is fine?" Reamer asked. "Why would you throw away bloody clothing in a dumpster if you think there’s nothing wrong with somebody finding it?"

Miller attacked Angela and Melanie as they cycled along the canal, murdered them, mutilated them, and had sex with their bodies for one reason, Reamer said.

"Because that's what he likes to do."

Defense attorney RJ Parker said it was more complicated than that. A lot more complicated. There were discrepancies in Miller's life too big to ignore.

The awkward passive father and the sadistic canal murderer. The immature 20-year-old who could barely remember to shower, let alone reliably pay rent, and the man who had planned, executed and gotten away with two notorious murders for decades.

"You have to ask yourself why? What else is going on here?" Parker said. "That's a tough question. But the answer is resolved by a complex dissociative disorder."

Miller hadn't approached the case with guile, Parker said, hadn't tried to embellish his trauma. He didn't recall things that might have bolstered his defense, like slashing vaginas into his mother's Barbie dolls, or the cookies incident that was so vivid in his cousin's mind.

When he killed Angela and Melanie, Parker said, the trauma state was firmly in control.

"He can’t accept having committed these offenses," Parker said. "You know why? Because it would destroy him."

The arguments ended on a Thursday. There were jury instructions, which everyone agreed Cohen should read on her own time, rather than out loud to herself on the bench. She said she would deliberate in the jury room, to be free of distractions and close to the boxes of evidence.

She didn't take long. By Monday, Cohen had reached a verdict. She would deliver it at 2 p.m. the next day.

On Tuesday afternoon, people filed into the courtroom, about 30 in all. Many had come and gone throughout the marathon trial. Their connections to the canal murders varied, from friends of the victims' families, to people who knew Miller, to police who had worked the case, to Lynn Jacobs. They sat, anxious to hear what the judge had to say.

The room hushed as Cohen began to speak, her voice steady as she ran through the requisite preamble. It was the Superior Court of the State of Arizona, she recited, in Maricopa County, in the case of State of Arizona vs. Bryan Patrick Miller, also known as CR2015-102066.

Finally, her verdict approached.

"The court, the finder of fact in the above entitled action, upon my oath, finds the defendant, as to count one, first-degree murder, Angela Brosso, as follows," Cohen said.

Guilty.

Count two, first-degree murder of Melanie Bernas.

Guilty.

Count three, kidnapping of Angela Brosso.

Guilty.

Count four, kidnapping of Melanie Bernas.

Guilty.

Count five, attempted sexual assault of Angela Brosso.

Guilty.

Count six, attempted sexual assault of Melanie Bernas.

Guilty.

Life or death

The sentencing phase began seven days later.

It would roll on for two months. Cohen had two options: the death penalty or life in prison. And although the issues were as complicated as the trial itself, the decision came down to one question.

Did Miller deserve mercy?

The tenor of the testimony would change, delving into the emotional as well as the factual, as the defense team offered an even more expansive view of Miller's life. Again, abuse was at the forefront, the hurt and humiliation Miller had endured at the hands of his mother, Ellen. But Cohen would also hear about his participation in Steampunk and costuming, the nice things he had done for friends over the years, his relationship with his daughter.

All of these, defense attorney Denise Dees told Cohen, could be reason to spare Miller's life.

The defense played recorded interviews with several people who hadn't testified, but whose memories of Miller had been trawled over by expert witnesses. These conversations were informal, sometimes recorded on iPhones that fell over or in parks with planes flying overhead and the sound of children playing in the background.

The anecdotes ranged far and wide. An elementary teacher said she had been concerned after seeing scratch marks on young Miller's back in Hawaii. A high school friend told of how he had carried her books to class when she had a sprained ankle. A friend from the Steampunk community remembered Miller bringing his daughter to "build days" where they would make old-fashioned-looking guns out of toilet roll tubes and paint.

Randy McGlade, Miller's Aunt Barbara and a handful of others said they still wanted Miller in their life. They promised they would stay in touch with him in prison. Yes, they said, when questioned by prosecutors. They knew what he had done.

'Wonderful and dedicated father': Canal killings trial: Bryan Miller's daughter was 'everything' to him, court hears

Several people described Miller as a loving father.

His daughter was not among them. She was too emotionally fragile to testify, according to Deena McGlade, who is Randy's sister, and who cared for Miller's daughter, now in her early 20s, for a period after her dad was arrested.

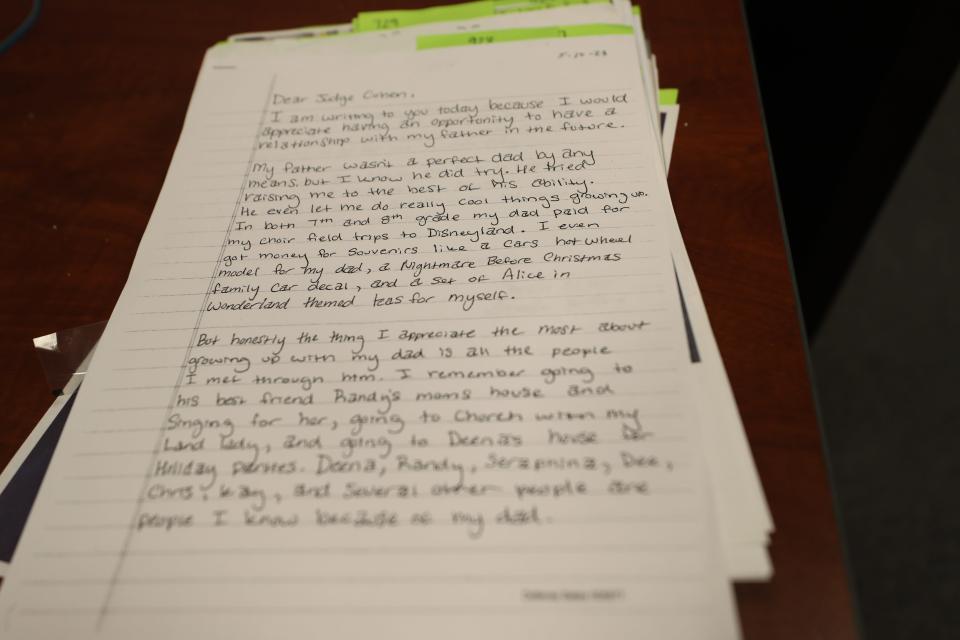

Miller's daughter had written a letter to the judge, and asked Deena to read it aloud. But as she prepared to do so on the witness stand, Cohen abruptly called the attorneys back to her chambers.

Later, in a motion for a new trial, the defense would say Cohen had tearfully requested Deena not read the letter aloud, told them she would read it and consider it, but she could not emotionally handle hearing it read aloud in court that day. They would suggest the incident revealed bias, perhaps unconscious, on Cohen's part, that it indicated a problem in her ability to separate judge and jury, that it showed she had already made up her mind.

When court resumed, Deena did not read the letter.

But it was entered into evidence.

"Dear Judge Cohen," Miller's daughter wrote.

"I am writing to you today because I would appreciate having an opportunity to have a relationship with my father in the future. My father wasn't a perfect dad by any means, but I know he did try. He tried raising me to the best of his ability."

Her dad had paid for choir field trips to Disneyland when she was in middle school, she wrote, even giving her money for souvenirs. What she appreciated most, though, were the friends he had introduced her to, Randy and Deena among them.

She ended with this: "Thank you for taking the time to read this, I know this is a difficult situation for you to be in and I appreciate all the people like you in situations like this."

Closing arguments

As Parker began his closing argument, he displayed a PowerPoint presentation. "Reasons To Choose Life" it read in white type on a blue background. Next to the words was a sepia-tinted photograph of Miller as a child, missing a front tooth.

"He was not born bad," Parker said.

He asked Cohen questions: Would Miller have gone on to kill Angela and Melanie if he had a different childhood? If he had a different mother? If he had not been abused?

If the answer was no, he said, Cohen should sentence him to life in prison. "You do not have to kill Bryan in order to see justice done," he told the judge.

'Immature' brain: Canal killings: Expert cites Bryan Miller's impaired judgment in murders

Parker described Miller as broken, unable to bear the weight of the trauma Ellen had heaped on him. "We should not kill broken people," he said. "We should work to rebuild them."

He read a poem Miller had published in the jail newsletter. Its final lines went like this:

"You expect to wade through my waters and see nothing / You look into my eyes and expect to see shallow depth / You look into my heart and expect to see an empty hole / Look into my soul and you will see, I am like the sea."

“There are parts of Bryan nobody knows," Parker said. "There are parts of Bryan Bryan doesn’t know, that he wants to get more in touch with because he knows there's a place of healing that he needs to get to."

"But the parts we do know, the parts he has shared with people … those are valuable, those speak to his humanity, and those are reasons for life."

The next day, Imbordino said he wasn't going to try to convince Cohen that Miller had a normal childhood. "I do think we still have to keep in mind his mother is not here to defend herself," he added.

But so what? He urged Cohen to look at the facts. At what Miller had done. He was asking for mercy, but had extended none to his victims.

He wasn't a child, Imbordino said. He didn't make a small mistake, misjudge a moral dilemma. He was 20, and he made a conscious choice to kill Angela and Melanie because it aroused him.

"You can try to dress him up however you want," Imbordino said. "He was referred to as being broken yesterday. But what he is at his core is a sexual sadist."

It was obvious from the violent pornography discovered in his home, Imbordino said. It was obvious from his words to Amy, in the letters he sent her from prison, and from The Plan.

It was obvious from his actions on Nov. 8, 1992, and Sept. 21, 1993.

As he spoke, Imbordino displayed pictures of Angela and Melanie. Not the images that nobody wanted to see. Happy, smiling photographs. The kind of snaps that should have been a fun throwback, a "Look at you there!" while flipping through an old album.

But they weren’t in an album. They were in evidence, marked with green Post-it notes as Exhibit 270 and Exhibit 271.

"This will sound harsh, I'm sure," Imbordino said. "Angela and Melanie didn't get to choose when they died. They didn't get to choose the day, the hour, the moment."

"This defendant deserves to know the day, the hour, of his death, for what he did."

Miller sentenced

June 7, 2023, 12:30 p.m.

The crowd gathered early, a handful of people mingling outside court an hour before Cohen would take the bench.

By the time the bailiff unlocked the door, the crowd had swelled, humming, moving inside quickly to find a seat. Melanie's sisters, who had been ensconced in a side room, settled in the front row, surrounded by friends.

Miller entered court the way he always did, a cardboard folder of documents tucked under his arm, closely followed by a correctional officer. But when he sat down, he briefly swiveled his head around to survey the waiting crowd.

For the first time in eight months, every seat in the public gallery was taken. The crowd rose and fell as Cohen entered, falling into silence as the solemn-faced judge began to speak.

She set a stake in the ground early: "There is no question the defendant deserves the death penalty."

But, Cohen continued, for 11.5 minutes in all, it didn't stop there. She had to look at who Miller was, not just what he did.

Her guilty verdicts had been one word only. This time, she had written a special verdict, 26 pages laying out what she had made of the months of evidence.

Of the multiple diagnoses, Cohen found four proven: depression, anxiety, hoarding disorder and sexual sadism. She did not find Miller had dissociative disorders or PTSD as the defense had contended, nor antisocial personality disorder, as had the state. He might have high-functioning autism, she said, but it wasn't proven in court.

She found Miller was an unreliable historian, but did not entirely discount his reports of Ellen's cruelty and abuse. It was clear, the judge said, that Ellen was not a loving mother, that her parenting had been inappropriate, hateful and cruel. It was unclear if Miller had been forced to watch "Shocking Asia" at the formative age he claimed, but even if he had been a teenager, it would have been "wholly inappropriate."

There was enough supporting evidence, Cohen said, to show Miller's childhood had been "marred by abuse and neglect."

This was significant, the judge said. So too was his age and immaturity in the early 1990s.

The crowd sensed Cohen was approaching her conclusion. The occasional whisper stopped. Nobody shifted in their seats. The courtroom, full to bursting, was more silent than it had ever been.

"The question the court must answer," she said, "is if the totality of the mitigation is sufficiently substantial to call for leniency."

Did Miller deserve mercy?

Cohen paused, briefly cast her eyes upward.

"The answer is no."

'You have to protect society'

After a brief adjournment, Parker rose to his feet and made an unusual statement.

"Your Honor, I would just say that it really has been a privilege getting to know Bryan for the past eight and a half years," he said. "And I just wish that you were able to see the same guy that we saw, because I know you'd feel a little differently in your heart right now."

As he spoke, someone seated close to Melanie's sisters made a loud noise ― just a cough, perhaps, or a protest.

Motion filed: Defense asks for a new trial in 'canal killings' case, calling judge's actions into question

Weeks later, Parker told The Republic the defense team had been surprised and hurt by Cohen's sentence. They had spent eight years getting to know Miller, he said, and it was hard to put how they felt that day into words.

"In sentencing Bryan to death, Judge Cohen’s verdict suggested she could not see Bryan as a human being whose life has value," he said, adding that Miller was not among "the worst of the worst."

"I regret that we could not help Judge Cohen clear barriers that prevented her from seeing the worthy person we’ve come to appreciate and care about."

In a motion for a new trial, the defense said Cohen was the first to suggest a bench trial. She brought it up at a conference in October 2021, they wrote, saying she had been thinking about the case in the early hours of the morning and thought it was something to consider.

After the defense and state agreed to waive a jury, the defense says, Cohen should have assessed herself for "unconscious feelings" about the brutality of the murders that might have swayed her from a life sentence. The motion is pending.

Cohen's decision will also go to an automatic appeal.

Lynn Jacobs lingered outside court long after prosecutors had left quietly with Melanie's sisters and friends, after the tearful defense hugs had ended.

He had come to know a lot of people involved in the trial over the past eight months. Other than a week in which he took his daughter to Florida, he had attended every day. He was the closest thing to a juror the trial had, even if ― as he readily admits ― he would have been booted in selection because he opposes the death penalty.

For that reason, he did not agree with the sentence. He did agree with the guilty verdict, but not because he wasn't convinced by the insanity defense. Jacobs is a father of three, and one of his adult daughters, the one he took to Florida, has autism. He was thinking about her as he sat through the trial, heard the diagnosis discussed endlessly. He even brought her to court one day, on a weekly outing from her group home, where she colored in pictures and gave one each to the state and defense.

Partly due to his experience raising her, Jacobs said, he found the defense case at least partly compelling. He believed the contradictions in who Miller was, and what he did didn't quite make sense. But the idea that he could be released into the community was anathema. So for those reasons ― which fall outside of what an actual juror would have been instructed to consider ― his verdict was guilty.

"You can empathize and sympathize as much as you want, but it comes down to practicality," Jacobs said. "You have to protect society."

Sitting through the trial had taken a toll, he said, right from the start, when Imbordino first displayed the crime scene pictures.

"You could pretty much use your imagination as to what was being seen," he said. "And you just watched the expression of the judge, and the people seeing them. And that was pretty heavy in itself."

Troy Hillman had been relieved to hear the guilty verdict back in April. It meant that no matter where Cohen fell on the sentence, Miller would be in prison for the rest of his life.

"As to whether or not he got death … I saw the pictures," Hillman said. "I saw what he did to those women. If that happened to my daughters, or my family? I'm sorry. I'd want the same thing. I'd want the death penalty."

Hillman doesn't think Celeste and Angela and Melanie were Miller's only victims, and he is not alone in that view.

He believes Miller was trying to kill the woman he was acquitted of stabbing in Washington state in 2002. He also thinks Miller is responsible for a different stabbing in the same state two years earlier, of a teenager named Victoria Mikelsen. Mikelsen has since publicly identified Miller as her attacker, but the statute of limitations in the case has expired.

Hillman is also among the many people who believe Miller murdered Brandy Myers, a 13-year-old girl who disappeared from north Phoenix on May 26, 1992. Her body has never been found.

"I think Miller did it. Absolutely," he said. "We just can't prove it."

Unmade memories

Throughout the eight months of trial, Angela and Melanie were barely visible.

Angela came into focus as Joe painted a picture of the life they had shared. Melanie as her sister, Jill Canetta, described the sibling she had lost. Both of them, briefly, as Imbordino displayed Exhibits 270 and 271.

But mostly, they shrunk in Miller's shadow.

"If you happened to join the trial at any time after the first two weeks, you'd have thought the defendant was the victim in this case," Canetta said.

She understood the legal process perfectly, Canetta said. She knew everyone had a job to do.

But still.

"She's not wrong," Cohen would later say, as she sentenced Miller to death.

The judge said she had never lost sight of Angela and Melanie as the trial had unfolded. But what happened to them had never been a mystery. The question had always been why.

Much is still unknown about Angela and Melanie's final moments.

Had Angela just set out, or was she almost home for "In Living Color"? Why did Melanie go riding that night? Did Miller deploy a ruse to stop them, or launch a blitz attack as they flew past on their bikes? How long did he spend up there on the berm with Angela, by the freeway underpass with Melanie, bringing The Plan to life? What happened to Angela's head in the 11 days between her murder and when a fisherman spotted it in the canal? Did he say anything to them? How many seconds passed before they slipped into unconsciousness? For how long were they afraid?

Miller isn't saying.

He did not testify, but exercised his right to allocute, making a two-minute speech to Cohen at the end of the sentencing phase.

He said he was not looking for sympathy. That he hoped his words did not cause more hurt. That he accepted the guilty verdict and hoped it provided "a measure of relief."

He did not say he was sorry for murdering Angela and Melanie. He did not shed any further light on what he did.

"I wish I could provide answers to the questions you have," he said.

The trial had weighed on the Brosso and Bernas families.

There was the pain of hearing, over and over, in gruesome detail, what had happened to Angela and Melanie, their terrifying ordeals squeezed into cold, legalistic language that was inherent to the process, but still diminished the horror of what happened. Hearing the minutiae of Miller's life, the wedding and child and social events he had gone on to enjoy, when for Angela and Melanie there was only a gaping absence.

He had taken Melanie's entire life, Canetta said, and a piece of all of theirs. Her absence had reverberated through the last three decades, always there, changing how they walked through the world.

And then there was the trial, the endless delays and the endless evidence, the family yet again dragged through, as Canetta put it, Miller's "dark world."

Every minute they spent listening, she said, was more he took from them.

With Angela and Melanie's pictures smiling down in Courtroom 5B, Imbordino urged Cohen to think about what Miller took from his two victims.

He stole their unmade memories, the prosecutor said. "He did not give them the chance to live their lives."

Some of those memories were enumerated by Linda Brosso, as she spoke to Cohen in the wake of the guilty verdict. "I've been waiting 30 years for this day," she said, her voice clear and raw as it rang out across the courtroom.

She had called Angela on her 22nd birthday, she said, only to be told she was missing. It was the start of a lifetime of calls not made.

"Angie won't be calling me to say, 'Happy birthday, Mommy.' 'Merry Christmas, Mommy.' 'I met the man of my dreams, Mommy.' 'I fell in love.' 'He asked me to marry him.' 'And I'm engaged. Can you help me plan my wedding?' She won't be calling to tell me about her honeymoon. Or, 'Mommy, I got the promotion at work' or 'We're going to have a baby and you're going to be a grandmother.'"

"I'll never again get to hold her hand," Linda said, "and kiss her smiling face."

All those memories. Gone.

'Canal killings' series:

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona 'canal killings': Miller gets death; families mourn victims