Hernández: Who is Canelo Álvarez fighting? Who cares? It's Cinco de Mayo in Vegas

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Secure the right venue on the right date and the opponent becomes almost irrelevant.

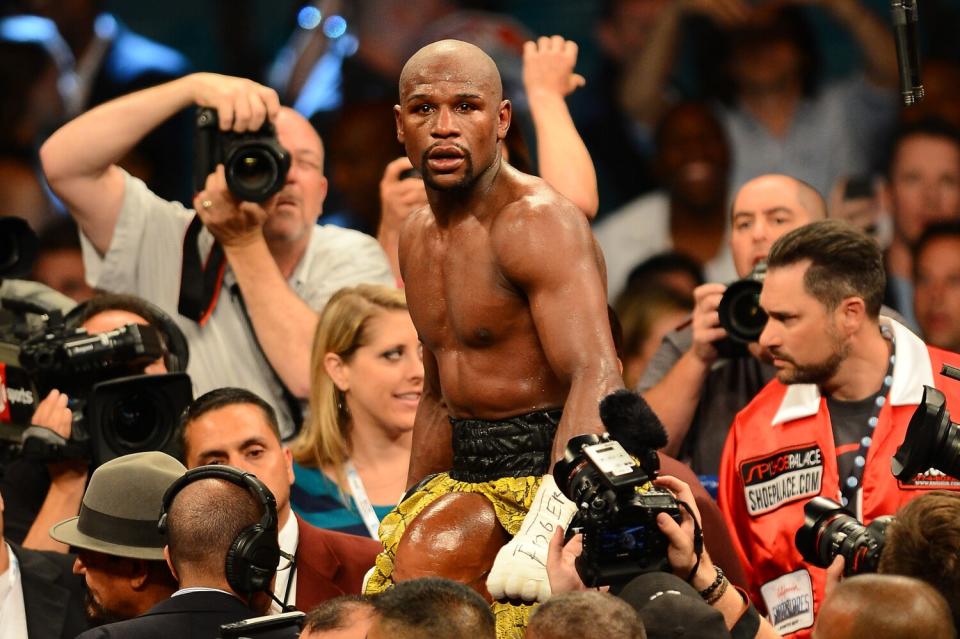

Floyd Mayweather Jr. knew this.

And now, Canelo Álvarez knows this.

After a pandemic-imposed two-year absence, boxing has returned to Las Vegas on Cinco de Mayo weekend.

The peculiar desert metropolis is welcoming back one of its more established sports traditions on Saturday when Álvarez headlines a show at T-Mobile Arena.

“I’m happy to be here representing my country on an important date,” Álvarez told reporters in Spanish earlier this week.

Who is Álvarez fighting?

Who is Dmitry Bivol?

Who cares?

The event will be as much a festival as it is a sporting competition. Mexican flags will wave on the Strip in the hours leading up to the fight. Street vendors will be hawking unlicensed merchandise. The scent of marijuana will be everywhere.

Around the country, especially in places heavily populated by Mexicans and Mexican Americans, families and groups of friends will gather for beer and carne asada in the afternoon, and more beer and the pay-per-view broadcast of Álvarez’s fight at night.

Which isn’t an accident.

The modern incarnation of Cinco de Mayo was a creation of beer companies in the late 1980s. The gambit worked. Americans purchased more beer on Cinco de Mayo than on Super Bowl Sunday or St. Patrick’s Day in 2013, according to Nielsen.

If anything, boxing is adaptable, its survival in times of declining popularity a tribute to exploit whatever opportunity presented to it. In September 2002, on Mexican Independence Day weekend, De La Hoya stopped Fernando Vargas. De La Hoya’s next fight was scheduled for September 2003, a rematch against Shane Mosley. De La Hoya didn’t want to be inactive for 12 months between fights. The solution: A tune-up against Mexican punching bag Yori Boy Campas on Cinco de Mayo weekend, which allowed De La Hoya to tap into this faux-patriotism to sell the mismatch.

With Latinos comprising a growing percentage of boxing’s audience, Cinco de Mayo has become one of the two cornerstones on the sport’s calendar, along with Mexican Independence Day.

What’s more American than sanctioned violence and alcohol on a made-up holiday in a make-believe city?

Cinco de Mayo has staged some major promotions over the years, including De La Hoya’s loss to Mayweather and Mayweather’s sleep-inducing win over Manny Pacquiao.

The weekend has also staged a number of fights of which the outcomes were never in question: De La Hoya vs. Ricardo Mayorga, Mayweather vs. Robert Guerrero, Álvarez vs. Julio César Chávez Jr.

Those fights attracted crowds, too.

Álvarez’s fight against Chávez was sold as a Mexican civil war, the new star against the son of the most emblematic athlete in the country’s history. When asked what was at stake in the showdown, Chávez initially offered lip service about pride before saying the truth: “The dates.”

In other words, the right to fight on future Cinco de Mayo and Mexican Independence Day weekends.

That right was previously passed from De La Hoya to Mayweather, who ingeniously marketed himself by amplifying traits deplored by many Mexicans and Mexican Americans: loud, brash and defensively inclined. Cinco de Mayo parties became hate-watching parties when Mayweather fought.

The day is now Álvarez’s, whose fight against Bivol will be his seventh as a main-event fighter on Cinco de Mayo weekend. Of the seven fights, only two were staged outside of Las Vegas, including a stoppage of Billy Joe Saunders last year in Dallas. Álvarez’s most recent Cinco de Mayo fight in Las Vegas was in 2019, a decision victory over Daniel Jacobs.

In Bivol, Álvarez will take on a fundamentally sound but robotic opponent. Bivol is relatively unproven but stands 6 feet tall and will have a 4½-inch height advantage over Álvarez. Bivol is a natural 175-pounder, while Álvarez is most comfortable at 168 pounds. The superior size of the Russian fighter born in Kyrgyzstan should help him survive into the late rounds.

Álvarez’s uninspiring choice of opponent is reflective of the sport’s landscape. Virtually every potential opponent is unknown to the general public, save for Gennady Golovkin, whom he is scheduled to fight in September. Golovkin is 40 and very much looked his age in his most recent fight.

That’s probably why Álvarez floated the idea of taking on Oleksandr Usyk, who holds a share of the heavyweight championship. That’s also probably why Álvarez and promoter Eddie Hearn talked about taking their show on the road and fighting in countries such as Mexico, Japan and England.

Without a notable opponent at or around his weight class, Álvarez needs something to sell his fights.

Except on Cinco de Mayo.

The weekend sells itself.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.