Cannes Review: Brett Morgen’s David Bowie Documentary ‘Moonage Daydream’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

David Bowie unquestionably became a great rock star—the greatest ever, according to a tribute published by Rolling Stone after his death in 2016. Yet, it comes closer to the truth to call Bowie a “rock star,” the quotation marks suggesting that what Bowie created was a persona of the rock god, in much the same way that Cary Grant manufactured the quintessential image of the glamorous “movie star.”

This is not to take away from his genuine accomplishments as a singer, songwriter and musician—he couldn’t have forged such a compelling persona without those gifts. Bowie’s real project was making art, and rock music and performance are best understood as just some of his modes of artistic expression.

More from Deadline

'Moonage Daydream' Trailer: First Look At David Bowie Doc From Oscar Nominee Brett Morgen

Neon Takes North America On Alice Rohrwacher's 'La Chimera' - Cannes

David Janove

Brett Morgen’s documentary Moonage Daydream, which premiered in the Cannes Midnight Screenings section, does supreme justice to Bowie by presenting him above all as an artist intent on exploring not only popular music, but painting, video, writing, dance, and film and theater acting. Morgen’s purpose isn’t for the audience to “learn” about Bowie so much as to experience him—to be pulled into the worlds and guises he created and to feel his creative and intellectual force.

In 2017, a year after Bowie’s passing, his estate granted Morgen access to “over 5 million assets,” including “rare and never-before-seen drawings, recordings, films, and journals.” The director crafts those materials into a sonically and visually immersive piece of cinema, with a thundering soundtrack that literally shakes the seats (at least where I was sitting). Morgen begins with an early performance by Bowie, already a hypnotic figure on stage. He didn’t reach out to the audience like an ingratiating performer—he drew them into his orbit with the gravitational force of his presence.

Owen Humphreys/PA Wire URN:58282210 (Press Association via AP Images)

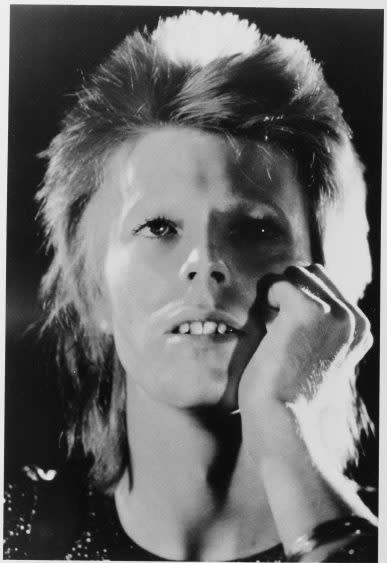

The reference to the laws of physics would become only more appropriate as Bowie’s career took off in the early 1970s and he introduced the alter ego of Ziggy Stardust, the messianic, androgynous, space alien rock star who brought a message of hope to planet Earth (the character was introduced in the single “Moonage Daydream,” the third track on 1972 album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars). Bowie’s exotic and entrancing appearance and the openly “omnisexual” character of Ziggy seemed to baffle straight-laced commentators at the time, who conflated Bowie with his artistic creation.

“Who is he, what is he, where did he come from?” Dick Cavett says in an archival clip in Moonage Daydream, introducing Bowie as a guest on his talk show in the 1970s. “Is he dangerous, smart, dumb… crazy, sane, man, woman, robot, what is this?”

Cavett inadvertently touched on something relevant by raising the question of mental illness, which afflicted Bowie’s family. The documentary eschews much in the way of biographical detail, but Bowie does talk about his half-brother Terry Burns, whom he credits with igniting his sense of intellectual curiosity. Burns gave his half-brother a copy of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, which Bowie cites as influencing him greatly. Burns would later develop schizophrenia, and required long-term hospitalization.

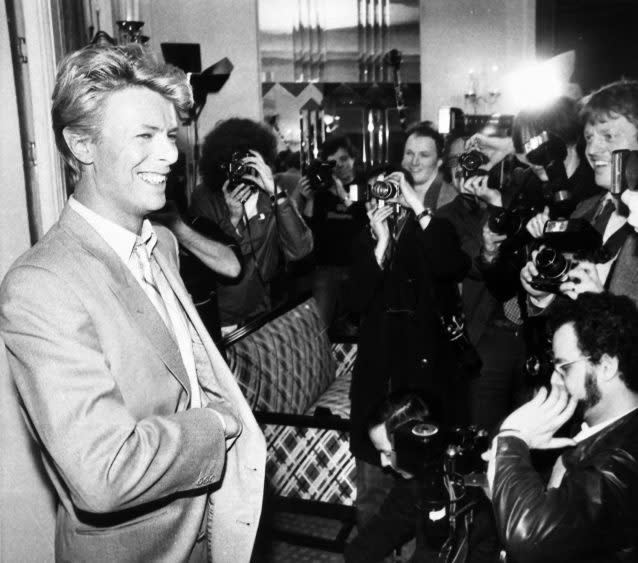

AP Photo

Bowie speaks in the film of consciously developing “a strategy to avoid the pitfalls of mental illness.” That strategy was to make art. It becomes clear in the film how Bowie used his own physical form as a canvas—costuming himself as an artist might dress a figure in paint. It didn’t end there. Bowie hasn’t been given sufficient credit as a kind of modernist dancer—in the film he’s seen molding himself into shapes almost like he’s using his body as sculpture.

Morgen, the director of documentaries on Kurt Cobain and the Rolling Stones, also edited Moonage Daydream, a stunning achievement in itself. At regular intervals he cuts in a dizzying blast of cinematic images, possibly intended to give a sense of the visual references that careened around Bowie’s head. The fragmentary shots originate from a variety of sources, including Nosferatu (1922), The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), Triumph of the Will (1935), The Seventh Seal (1957), La Dolce Vita (1960), A Clockwork Orange (1971), and Blade Runner (1982).

These repeated flashes of imagery, as well sequences of star-filled skies, planets in eclipse, and Bowie on stage in “alien” persona lend a delirious quality to the film, keeping it experiential instead of biographical. Nonetheless, Moonage Daydream does cover the stages of Bowie’s career, including his conscious reinvention as a songwriter after he moved to West Berlin later in the 1970s. Collaborating with musician-composer Brian Eno, Bowie in Berlin delved into more abstract forms of music. The Serious Moonlight Tour of 1983 came in the midst of Bowie’s biggest commercial success with the album Let’s Dance, the only artistic phase that Bowie possibly regretted.

The film captures Bowie’s consistent desire to explore new terrain—be it spirituality or the work of Nietzsche, or new environments. This is where the influence of On the Road becomes most apparent. “I detest L.A. so I went to live there,” Bowie explains at one point in the film.

AP Photo/Redman

Some of his personae could seem aloof or even (arguably) fascistic like the Thin White Duke. Yet in the film he comes across as warm and witty.

“I don’t want to seem as if I’m cold and detached,” he says, “because I’m not.”

Bowie seems to have genuinely loved life, one of the film’s biggest revelations. And he had a real, even old-fashioned love story with his second wife, the supermodel Iman, whom he married in 1992 and remained with until his death.

Bowie once described himself in a Rolling Stone interview as an “addictive personality,” and he spoke openly about abusing cocaine, particularly in the 1970s. Morgen’s film doesn’t get into the drug use, but Bowie is seen smoking cigarettes constantly. He was diagnosed with liver cancer in 2014 but chose not to publicize it. He remained artistically active until the end.

More than six years after Bowie’s death, Moonage Daydream reminds us how unique Bowie was as an artist. He was ahead of his time–ahead of our time. His experimentation with gender fluidity in the 1970s prefigured today’s debates about gender identity. The eeriness of Major Tom’s lonely journey in outer space seems to forecast our own potential need to abandon a ruined Earth in some distant future.

What Moonage Daydream captures most forcefully is Bowie’s capacity and desire to change, to transform, to entertain new creative ideas. As he says in the film, “I hope that none of us are static throughout our lives.”

Moonage Daydream will be released in theaters domestically by Neon in September; Universal Pictures Content Group will handle international distribution. HBO and HBO Max will stream the documentary next year.

Best of Deadline

2022-23 Awards Season Calendar - Dates For The Oscars, Emmys, Tonys, Guilds & More

NFL 2022 Schedule: Primetime TV Games, Thanksgiving Menu, Christmas Tripleheader & More

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.