'You can't explain': Lakeland man treated the wounded in Vietnam, and his own trauma

Men who served as Navy hospital corpsmen with the Marine Corps during the Vietnam War faced daunting odds – a nearly 40% chance of being killed or wounded.

Many were specifically targeted by the Vietcong and North Vietnamese for a simple reason: Picking off a medic in a firefight was a force multiplier because their wounded American comrades, who otherwise might have survived, were more likely to die for want of immediate care in the field.

Of the approximately 10,000 Navy hospital corpsmen who served as medics with the Marine Corps between 1965 and 1974, more than 3,000 were wounded and 645 killed. In every sense, their service was as perilous as that of a combat soldier. It is no coincidence that of the 268 Medals of Honor – the nation’s highest military decoration – awarded to American servicemen for duty in Vietnam, one out of every 20 went to corpsmen and medics. Many more were awarded the Navy Cross – the service’s second highest combat honor – the majority posthumously.

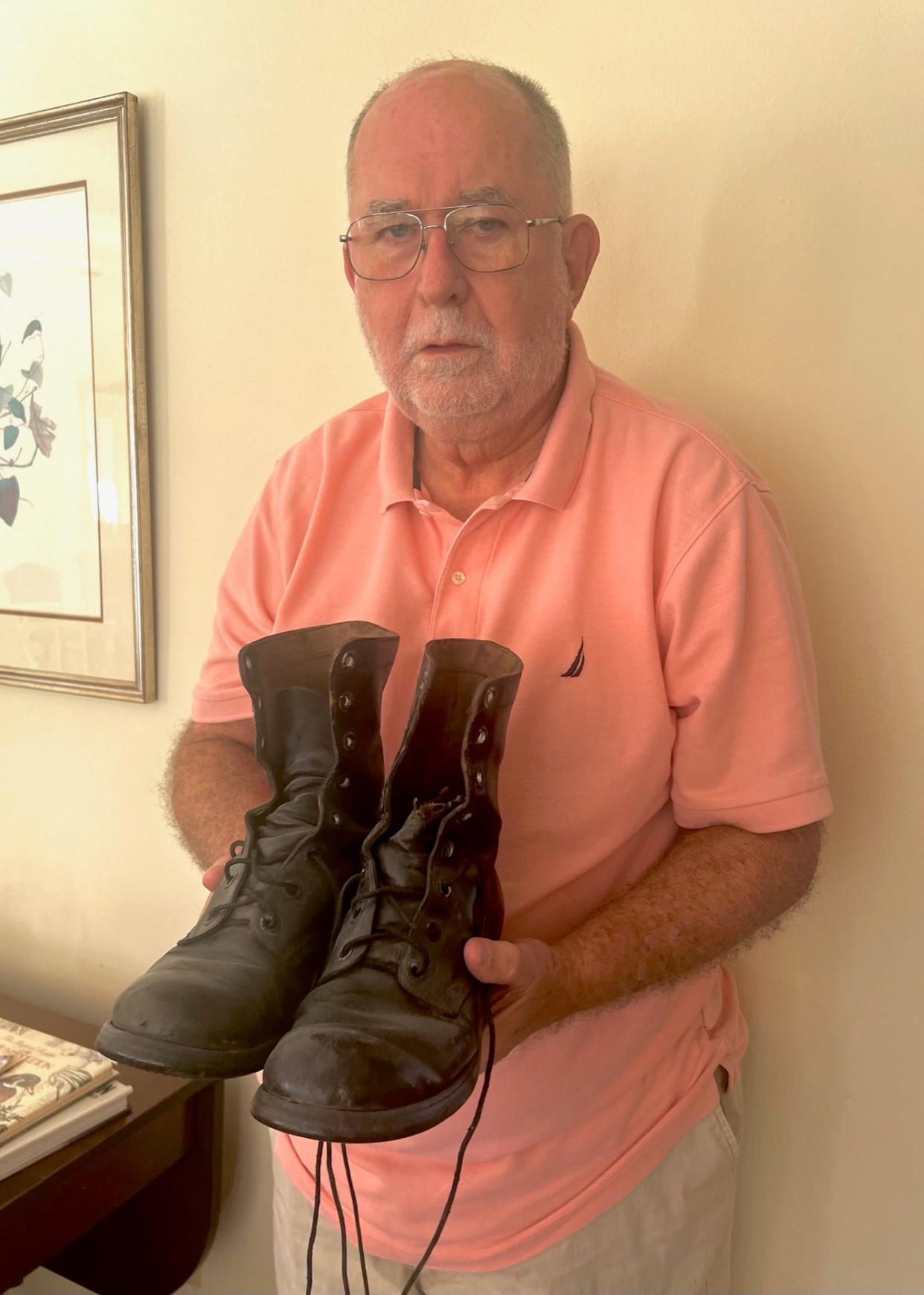

Among those who were wounded is Lakeland’s Max Hauth, 77. An Illinois farm boy who started plowing fields in the third grade, Hauth had by age 19 been recently licensed as a barber and was attending college part-time with aspirations to become a dentist. The war’s need for practitioners upended his plans. Facing an Army draft, he became a sailor, imagining that after boot camp the Navy – always in need of barbers – would assign him that duty.

He had yet to learn the ways of the military. Instead, he was sent to hospital corpsman school. After graduation and following duty at a stateside Navy base, he was assigned to the Marines and ordered to Vietnam.

Q. Before deploying to Vietnam, you – a Navy guy – first had to be integrated into the Marine Corps. What was that like?

A. Fleet marine field training was done at Camp Pendleton, and I was there for a month. They had their own idea of fun and games – long hikes, putting up tents in the middle of the night, climbing nets, running courses, assaulting hills, combat training. They gave us an M14, which was a relic, but being raised on a farm – hunting and so forth – I knew how to shoot.

Q. Did you have an opinion about the Vietnam War prior to being deployed there?

A. I had already lost two high school friends, early casualties of the war, but the war really wasn’t going full steam at that point. It was kind of in its infancy but was kicking up and becoming much more featured in the news. My thought was that if we’re going to do something helpful to bring a positive outcome, then it’s probably worthwhile to participate.

Q. When you arrived in-country in May 1967, what was your initial exposure to the war?

A. It was kind of a shock. I spent a couple nights at the airbase in Da Nang, waiting to be taken out to where I was being stationed. It was about a 15-mile jaunt to the battalion’s location. The truck we were in had no armament except for what the driver was carrying. The truck that followed us was armed – we were 20 minutes ahead of them – but got hit and two people were killed in the ambush. We were unloading when the other truck came in with the casualties. It was – whoa, we’re in a war.

Q. What unit were you attached to?

A. I was stationed with First Battalion, First Marines, attached to Bravo Company when I started going out in the field. When I first got there the group I was with did a company sweep – several hundred Marines – and then it got broken down to smaller units. We’d do patrols, maybe with 30 guys and two corpsmen. Or we’d go out with a squad – how many people depended on how many had already been wounded or killed.

'My childhood friends' Winter Haven grads, Army officers died in Vietnam17 months apart

Q. In addition to your cache of medical supplies, were you armed?

A. I carried a 45 pistol. Supposedly I was a non-combatant, except when people were shooting at me – then, when I had to. There were times when I carried an M14 because the M16 was a relatively new weapon and tended to have issues – and that led to times when we were taking a lot more fire coming at us than was going out.

Q. When was the first time you had to treat somebody in combat.

A. About four days after I went out in the field, we hit a trail that was booby-trapped. The Vietcong would take a hand grenade, stick it in a c-rat can, pull a string across, somebody would come along and trip the string. Generally, they’d cut the fuse so when it came out it didn’t have a delay, just bang. The person had shrapnel wounds to the lower extremities. When you hear “corpsman up” they expect you to make a house call – and you do. We were in an area where we could call in a helicopter and evacuate him.

Q. What part of the country did your unit patrol?

A. We were mostly in an area we called the mud flats – old rice paddies – about 15 miles out of Da Nang, which was a free fire zone. There were supposed to be no Vietnamese civilians. Sometimes people wandered into the area who were not friendly. I got wounded twice in that area. The first time I was riding on a tank, a brand-new tank, only been in-country about 48 hours, and they had me riding behind a second tank. They said, “If you’re riding back there, Doc” – that’s what I was always called – “you’re safer than on the front tank. If something happens, we want you to be available to take care of us.” Sounded like good, logical thinking.

Whether it was triggered by an individual or by concussion was not determined but we hit an explosive device buried in the ground that was estimated to be comparable to a 500-pound bomb. It cracked 11 inches of homogenous steel from the bottom of the tank, blew the treads and put a hole in the ground the size of this room.

I lit some distance from the tank. They said I looked like a rag doll flipping through the air. I landed on the side of a dike where punji stakes had been placed. But the blast was such that it cleared that area of punji stakes before I hit. My adrenaline was going crazy. I evacuated all the casualties except for myself. One of the Marines came up and said, “Doc where are your glasses?” I didn’t realize they were gone. They were found underneath the tank, along with my helmet. Luckily I wasn’t still with the glasses or helmet. And we were lucky we didn’t have a secondary explosion within the tank – especially when you saw the damage. It was junk.

A lot of people had concussions, major injuries. But it was getting dark so I couldn’t evacuate myself out. I had to wait until the next morning. They did an evaluation – I sustained a back injury, they treated me and sent me back within a week.

Q. And the second time?

A. I was back in the field about three weeks later and was riding on another tank. We made a run through an area and we were following our tracks back through the same area, not gone for very long. Coming back, we hit a buried mine with about 100 pounds of explosives. A couple of guys on the back of the tank with me had injuries. I got a concussion and a perforated eardrum. Back at the aid station they evaluated me, packed my ear, sent me back to the field the next day and told me to “avoid loud noises.”

Q. Did you ever get to the point that you thought, my luck’s about to run out?

A. About every day. It’s strange. You might go out on four or five patrols for a period of time when nothing’s said. And then you’re getting ready to go out on another patrol and somebody in the group would make a comment – “I wonder who’s going to get hit today?” – and invariably something would happen. Whether it’s because of the area we’re going into or some other unknown reason, you don’t know – but you wonder why.

Q. Close calls seem to have been part and parcel of your experience. What else stands out?

A. Alpha company went out doing a sweep through an area near the DMZ one day and came under fire. They called in for medical assistance. At that point I was in the battalion aid station underground with a couple of the doctors. I got the nod along with another corpsman who happened to walk in and I commandeered him. We went out in an amtrack and parked it some distance from where Alpha company was pinned down, with 26 wounded at that point. We ran across the rice paddy to get to them. We’re working on some of the guys and the artillery director with Alpha is telling them to add 50 on the range that was coming our way. And the reply that came back was, “We’re not firing any.”

When I left the amtrack I’m hearing “thump thump thump” and the dike I’m running by is disappearing. I’m lying down behind the dike and look up and hear that “thump thump thump” again and the dike ahead of me is disappearing. The place that the dike wasn’t shot away happened to be where I’m lying down. I take off running to get the wounded out. One of the guys is running toward me in a ditch area and he gets shot – a through-and-through gunshot wound in the leg, didn’t hit anything major. Whether it was shock or something else, he fell into me – dead.

'It's keeping us young' Winter Haven grove finds niche selling organic lemons

Of the 26 wounded who we got on the amtrack there were six KIAs. I’m in the amtrack working on one guy with a head wound as well as other wounds. He’s lost an eye and I’m thinking he’s dead but I’m not giving up. Pretty soon I hear a gasp and I think, “Oh God, he’s taking a death gasp. Then I hear it again and then again, louder – and he’s breathing. Time has elapsed and he comes to – he was all but gone – and he says “Doc, I’m going to make it, don’t worry.” I told him, “You were dead.” He said, “I didn’t want to come back. I was met by some of my relatives and at the same time I knew what you were doing to me.” It was like he was standing outside himself.

Q. Did you have trouble adjusting to civilian life after Vietnam?

A. Yes. Now the service tries to do more for members when they’re coming near discharge time. Back then it was cold turkey – deal with it. Coming back home, the veteran just didn’t get much support. We also didn’t deal with PTSD – the attitude was “You’ve got mental issues, suck it up.”

When I got back home, I was in a Kmart with my sister and her little boy and we’re walking down the aisle in the toy section. Somebody fired off a toy that sounded like a carbine. You develop certain instincts that make the difference between life and death and I found myself lying on the floor. People were laughing at me. People just didn’t have respect for the returning veterans.

Q. Hundreds of thousands of Americans rotated through Vietnam. Though the vast majority never saw combat, more than 58,000 died. You might well have been one of them. Your thoughts?

A. It’s hard to explain – and you can’t explain – why certain things happen the way they do. A personal example: the Marine on point triggers a device and is killed. The man behind him is wounded. The two people behind you are wounded. You’re knocked to the ground but are uninjured. Why? I’ll tell you what: It makes you believe. And if you have more than one incident, it makes you believe even more.

This article originally appeared on The Ledger: He treated wounded men in Vietnam. Then dealt with his own pain