Canvassers descend on Phoenix for one last push. What's it like on both sides of the door?

If dogs could vote, Victoria Stahl's life would be a whole lot easier.

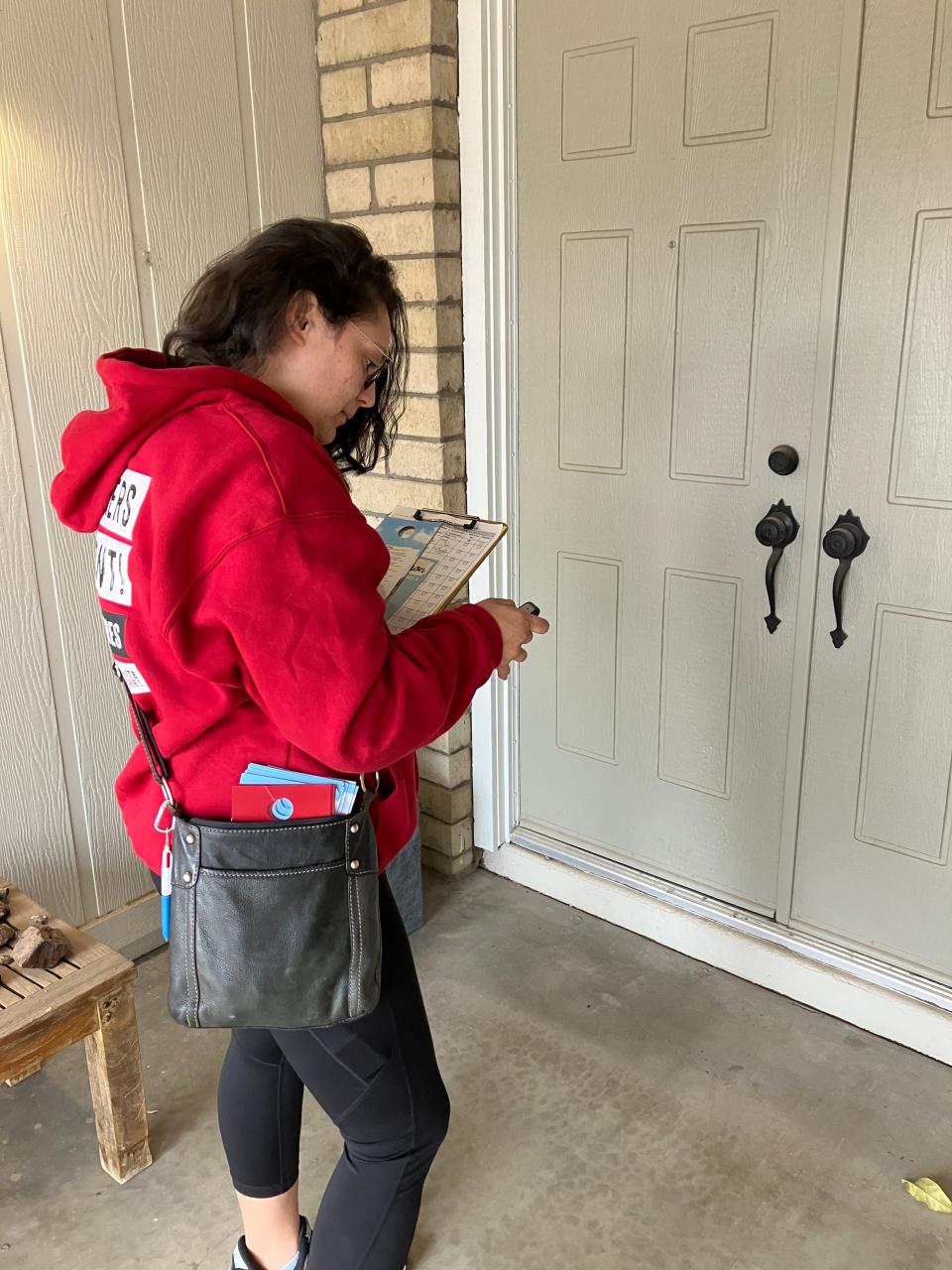

As she trudged from house to house in Ahwatukee on Thursday in search of registered voters, she was met mostly with frenetic barking behind doors that never opened.

It was cold and miserable in Phoenix, but with Election Day looming, there was no caving to the weather. The 25-year-old barista juggled an umbrella alongside her clipboard, flyers and phone.

She stopped at her first door of the day and rapped out her signature jaunty knock with a metal clasp on her keyring.

"It just makes it a little bit louder so people can actually hear you," she said.

She waited 20 seconds. Nothing. Rat-tat-ta-ta-tat. Another 20 seconds of silence. Rat-tat-ta-ta-tat. Zilch.

Stahl left behind a couple of flyers and moved on. The next door triggered barking. The one after that, nothing. The wind and rain picked up, turning Stahl's umbrella inside out.

She knocked on the next door and heard a howl. Another canine non-voter. But then, the door opened a crack, and a man peered out. Stahl was finally in with a chance.

"Hi, how are you?" she said. "I'm just talking to folks in the neighborhood about the election."

"I don't talk to strangers about politics," he said. "Sorry."

Politics: Here are the results for Arizona's Nov. 8 midterm election

'Every door counts'

An army of canvassers has descended on metro Phoenix this election cycle, going door to door in a bid to turn out every last vote.

They talked to voters about candidates and causes, shared their own stories, handed out flyers, told people how and where to return their ballots, and, sometimes, had doors slammed in their faces. Most are volunteers or paid workers, but the candidates themselves have done plenty of walking.

At some houses, no one is home, or at least they pretend not to be. At others, the door opens to a friendly face, or a hostile one, or someone with an axe to grind. Occasionally, the visit goes perfectly: One couple were so impressed by a candidate they not only promised to vote for her, but wrote her a check and set up her signs in their yard.

But it all starts with a knock.

Earlier on Thursday, Stahl had gathered with about 50 others canvassers in the parking lot of a Tempe business park.

A nervous, determined energy rippled through the group during a pre-canvass pep rally. Some bounced from foot to foot to stay warm as they stood in a large circle and listened to lead campaigners stress the urgency of capturing every vote.

"Every day matters," was the message. "Every door counts."

They were there to canvass for the union Unite Here, which represents 300,000 workers in hotels, airports and food services across the U.S. and Canada.

Among its members is Stahl, a Phoenix native who was raised in Maryvale. She usually works at a Starbucks in Phoenix Sky Harbor International airport, but has been on a leave of absence for six months to campaign.

After a rousing chant of "Si se puede! Si se puede!" — "yes we can," a famous slogan of the farmworkers' labor movement — the volunteers broke up into small groups, one of them led by Stahl.

"How many days do we have left?" she asked, as four canvassers gathered around her.

"Eight, seven, nine?" one said. "I just took a random guess."

Stahl held up her hand, fingers outstretched.

"Oh!" said the canvasser. "Five!"

"We are very very close," Stahl said. "It's pushing everything you possibly can across the finish line to get there."

Unite Here identified Arizona, along with Nevada and Pennsylvania, as a key battleground state in the midterms. Its 300 paid canvassers in Arizona, a mixture of full and part-timers, have been out talking to people since June and knocked on 500,000 doors.

On Thursday, Stahl's group was tasked with 80 doors each. But it wasn't about hitting targets, she said. It was about having genuine conversations, making a plan with the person to vote, and then following up.

"Don't meet your goal, beat your goal," Stahl told the group. "That's what I want y'all to do."

Team effort: Jill Biden comes to Arizona to campaign for Sen. Mark Kelly

'Not strangers anymore'

Back at the Ahwatukee door, Stahl is undeterred by the man who doesn't talk about politics with strangers.

"Yeah, no, totally," she said. Then she started talking about politics.

She told the man she has lived in Arizona her whole life and is passionate about the public schools here. Then she pivoted straight to abortion.

"I have arthritis," she said. "There's medication that my doctor won't prescribe to me because it could possibly cause a miscarriage."

She wants to elect people, she told him, who will allow her to make her own decisions about health care.

"I'm with you there," the man replied.

Stahl smiled and said "So, hopefully we're not strangers anymore. You know a little bit more about me."

The man laughed.

By the end of the conversation, he told Stahl she could count on his vote for several Unite Here-endorsed candidates, including Democrats Katie Hobbs for governor, Mark Kelly for Senate and Adrian Fontes for secretary of state, as well as Phoenix City Council candidate Kellen Wilson.

Walking to the next house, Stahl said she talks about abortion with a lot of people.

"People have sisters and daughters and mothers," she said. "And like, whether or not you agree that abortion is right or not, I think we can all agree that my health care decisions about my arthritis shouldn't be decided by somebody who is in office."

It also builds intimacy, she said. She goes from being an annoying stranger to a human being who has real issues at stake on the ballot.

She also often talks about her job. Stahl's employer is HMSHost, which operates food services at Sky Harbor, which is owned by Phoenix. The City Council race is particularly important to her, she said, because the outcome can meaningfully affect her working conditions. Stahl was among the airport workers who went on strike last year to win changes to health insurance and pay.

Stahl has been having these conversations with voters six days a week, eight hours a day, since mid-September.

The union uses a popular canvassing app called MiniVAN that shows users which houses they need to hit, the name and age of the registered voter who lives there, whether they've voted yet, and any past canvassing visits.

That's how she knows the occupant of the next house is a 23-year-old woman. She's probably not going to be home, Stahl said.

Three knocks and one disrupted dog later, the woman pulls into the driveway just as Stahl is about to leave.

"I already voted," she told Stahl. Was it for Hobbs, Kelly and Fontes?

"I don't remember, honestly," she said.

Arizona voters: What to expect on election night

Closed doors and golden tickets

So far this election, independent voter Mandy Snowden has opened the door for one canvasser.

The conversation didn't change her vote. "I had pretty much made up my mind," she said.

But the 31-year-old believes more canvassers have dropped by her South Phoenix home.

"Sometimes I just don't come to the door," she said. For a while, she had a wreath blocking her peephole and couldn't vet unexpected knocks, so she just ignored them.

She felt "kind of bad" for the one she did open the door for, Snowden said.

"She was really nice, and she was really young, and she was by herself. When we parted ways, she was like 'Thanks for opening the door.'"

"I got the impression that probably not a lot of people do open the door."

Occasionally, canvassers can strike gold.

On a Saturday afternoon a couple of weeks ago, Richard Sinclair and his wife, Margaret, both 83, were at home in Scottsdale when a knock came at the door.

"And lo and behold it was a woman, and she introduced herself, she was Mary, and I forget her last name," Sinclair said.

Standing on the doorstep, the woman asked if she could take a moment to run through her positions. Sinclair said: "Well, why don't you come inside?"

They spoke for 15 minutes. By the end of the conversation, the Sinclairs had not only agreed to vote for her, but wrote her a check on the spot.

"And actually my wife was so impressed, she even suggested that she put her signs in our yard," he added. "My wife who hates political signs!"

Sinclair, who is the acting president of the Arizona Independent Voter's Network, acknowledged he is more informed than the average voter.

But still, he said, without the woman's visit, his school board vote would have been "a flip of a coin".

The woman at their door was Mary Gaudio, a candidate for Scottsdale school board.

Gaudio started canvassing in late February, pounding the pavement weekly all through summer. For the past six weeks or so, she has gone out almost daily. "I'm tired," she told The Republic, laughing.

Even so, she remembered the Sinclairs right away. "They were amazing," she said.

Gaudio is a staunch public school supporter running on a platform of equity and restoring trust within school communities. The Sinclairs were a high point, she said, but school board races have become increasingly politicized and other conversations have been "disrespectful."

"I have been getting a lot of the culture war conversations going on at the doors," she said.

People will ask her about critical race theory, or accuse teachers of encouraging students to try out new gender identities.

"They're convinced of it," she said. "It’s really quite, quite disturbing to me."

For Gaudio, canvassing for school board has been a window into the electorate.

"It’s really been informative for me on just gauging the temperature of politics in Arizona," she said.

She wishes more people would be willing to talk about politics face to face rather than relentlessly complaining online. But she believes canvassing makes a difference.

"It is in my mind so much more impactful when a candidate, especially in a down ballot race, comes to a door," Gaudio said. "They’re always surprised."

"And a lot of them say, 'Wow. You must really want to have this unpaid job.'"

Coffee and politics

Stahl loves canvassing. Part of it, she said, is never knowing who you're going to talk to, or where the conversation will go.

A big part of it is about convincing people their vote matters. "Even if you don't pay attention, or, like, you don't know the ins and outs of everything, you still deserve to have a voice and it still deserves to be heard," she said.

She likes working at Starbucks too, in part for the same reason — "I love being able to talk to people and meet people" — but also because it's fast-paced, making drinks is fun, and she has great co-workers. (Not to mention the free coffee.)

She has a generous approach to demanding customers who order five minutes before boarding their plane.

Election guide: November 2022

City races | School boards | State | Governor

| Ballot measures | Federal races | How to vote

"One of the things that we are, like, constantly trying to remind ourselves is that we don't know why people are flying," she said. "People could be flying to go to a funeral."

But she isn't sure when she'll return to making drinks.

If there's a run-off election in Georgia she might go and canvass there. She might do communications work with the union. Starbucks might need her back for the holidays, or they might not.

Right now, none of it matters.

"I'm just focused on Election Day," Stahl said, as she walked to the next door, ready for whatever it would bring.

Reach the reporter at lane.sainty@arizonarepublic.com. Follow her on Twitter @lanesainty.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Army of canvassers descends on Phoenix in the election's final hours