Caprock Chronicles: Alaska highway allowed military traffic to far West outposts, Part 1

Editor’s Note: Jack Becker, Librarian Emeritus, TTU Libraries is the editor of Caprock Chronicles. He can be reached at Jack.becker@ttu.edu. This week’s Caprock Chronicles is written by John McCullough, author and aviation historian of Lubbock, who holds a master’s degree in history from Texas Tech. This article is the first in a two-part series about the Alaska highway.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on Dec. 7, 1941, the United States and Canada feared that the Japanese might invade Alaska or the Aleutian Islands, which jut westward in the northern Pacific Ocean towards Japan. Once Japanese troops were in Alaska, it was believed that they would march into Canada and then down into the northwestern region of the U.S. Officials also fretted that the Japanese might use airfields in the Aleutian Islands as bases from which to bomb the west coast of the U.S. and Canada.

To counter this threat, officials proposed building a highway from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, in Canada, northwest to Fairbanks, Alaska. Troops and military supplies could then be trucked quickly to cities and military posts in Alaska. It was one of the most ambitious construction projects of the early part of the war and involved thousands of civilian workers from the U.S. and Canada. When completed, the Alaska highway was about 1,671 miles in length.

The Lubbock Avalanche-Journal was filled with dozens of articles about the Alaska highway and its potential economic and cultural impact upon Lubbock and West Texas. Originally named the ALCAN (Alaskan-Canadian) highway, the more commonly used name, Alaska highway, was adopted as final refinements were nearing completion in 1943.

Some officials proposed extending the Alaska highway south through Canada to the Great Plains states. From there, they wanted to see the highway branch out and meander south to the ports of lower Texas, the Rio Grande Valley, and eventually Mexico. Lubbock’s leaders wanted to have one of those branches routed through the Hub City.

Construction of the Alaska Highway began in March 1942. Fears of the Japanese Army invading, and occupying Alaska and the Aleutian Islands proved to be well-founded. Following Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle’s air raid on Tokyo on April 18, 1942, the Japanese attacked the Aleutian Islands on June 3. A two-carrier task force with supporting ships carried out the initial attack, which resulted in 44 U.S. servicemen killed and another 49 wounded.

By July, Japan had placed an estimated 10,000 troops on several of the Aleutian Islands, specifically Attu, Kiska, and Agattu. With Fairbanks, Nome, Anchorage, and other cities and settlements on the Alaskan mainland at risk of being overrun by Japanese forces, the need for a highway running from Canada to Alaska to bring troops and supplies to this far-west U.S. territory was given high priority.

On September 29, trucks were traveling over many areas of this new, but still primitive, dirt highway including those areas around Fairbanks, Alaska and Fort St. John, British Columbia, which was located near the southern end of the road.

The entire road was open to military traffic by October 29, over a month ahead of schedule, Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, announced. Composed mostly of dirt, some limited stretches of the highway, however, were made of wood (corduroy roads) to improve passage.

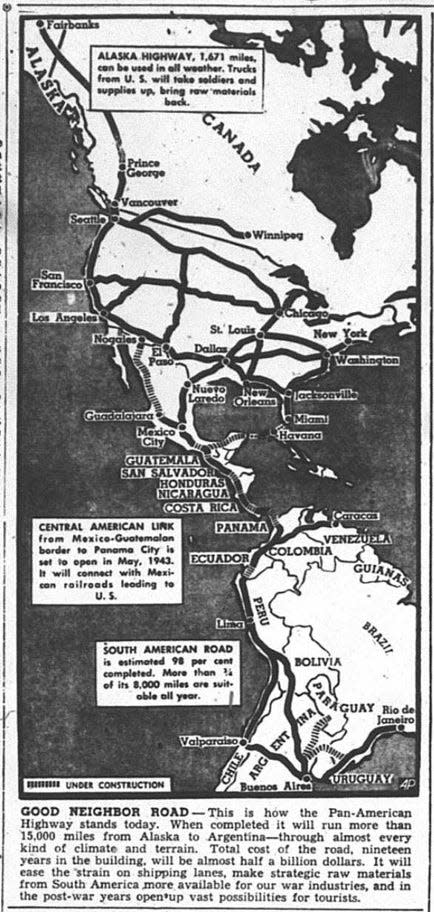

By November 27, 1942, the Avalanche-Journal reported that the Alaska highway was now being seen as part of the much larger Pan-American, or superhighway, with connections continuing south to Mexico, Panama, and to ports in South America.

When the Pan-American highway is completed, the Avalanche-Journal stated, “it will run more than 15,000 miles from Alaska to Argentina – through almost every kind of climate and terrain.”

“It will ease the strain on shipping lanes, make strategic raw materials from South America more available for our war industries, and in post-war years open up vast possibilities for tourists.”

This proposed superhighway, however, bypassed Lubbock and West Texas, much to the chagrin of Lubbock’s leaders. It was not long before they would be taking measures to have a branch of the Pan-American highway routed through the Hub City.

On December 18, 1942, the Avalanche-Journal reported that this new superhighway would stretch into the eastern U.S. along one route and west of the Rocky Mountains for the other route. U.S. Representative Hare (D-S.C.), envisioned “a defense highway circling the country and linking the Alaskan highway with the inter-American highway at the Mexican border.”

“Hare’s bill calls for the east branch of the defense highway to begin at a point near Minot, N. D., and proceed thence in the vicinity of Chicago, Knoxville, and Birmingham, before turning toward the lower border.”

“The western branch should start at a point near Glacier Park, Montana, and run west of the Rocky Mountains, swinging southward and inward until it meets the east branch at the Mexican border.”

Hub City leaders objected to having Lubbock and West Texas bypassed in this layout and worked strenuously in 1943 to have a branch of the Pan-American highway routed through town. What attempts they made to re-route part of the superhighway through Lubbock will be revealed in part two of this series.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: Caprock Chronicles: Alaska highway allowed military traffic to far West outposts