Caprock Chronicles: Footprints in the Sand: Was Clovis Man the first American?

Editor’s Note: Jack Becker is the editor of Caprock Chronicles and Librarian Emeritus, Texas Tech University Libraries. He can be reached at jack.becker@ttu.edu. Today’s article about the earliest Americans is by frequent contributor Chuck Lanehart, Lubbock attorney and award-winning Western history writer.

For almost a century, artifacts found near Clovis, New Mexico, were accepted by scientists as evidence the earliest American was Clovis Man, who once thrived on the Llano Estacado. However, a recent discovery indicates earlier humans may have lived nearby, sparking debate about when and how they got there.

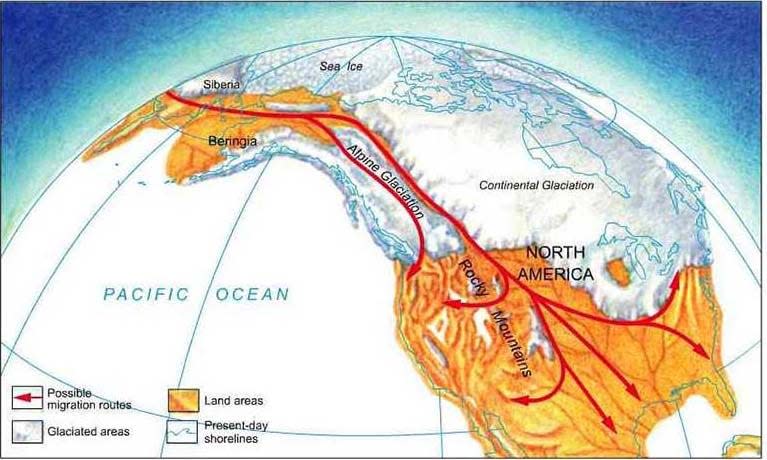

In 1927, a cowboy found a mammoth skeleton with a spearpoint in its ribs near Folsom, New Mexico, triggering interest in digging for evidence of early man in the region. Five years later, excavation 200 miles south in Blackwater Draw near Clovis unearthed projectile points and tools supporting the theory early humans crossed the Beringia land bridge over the Bering Strait from Siberia to Alaska during the Last Glacial Maximum, a period of lowered sea levels during the Ice Age. Ancient travelers may have made their way southward through an ice-free corridor east of the Rocky Mountains in present-day western Canada as glaciers retreated.

Researchers dubbed the subject of their findings the Clovis Culture, characterized by the beautiful, fluted stone spearpoints crafted by Clovis people and found at sites throughout the Americas. Clovis people — believed to be ancestors of all Indigenous Americans — spread across the continent between 13,500 and 11,000 years ago. Clovis people foraged and were skilled hunters of big game such as mammoths, mastodons, camels, horses, giant sloths and ancient bison.

The Lubbock Lake Landmark is an archeological site which preserves evidence of Clovis Culture. Material excavated from an ancient river valley shows evidence Clovis Man killed and butchered giant Ice-Age beasts here.

About 11,000 years ago, the Clovis Culture abruptly vanished from the archaeological record, and other hunter-gatherer cultures emerged. Their disappearance coincided with the extinction of ancient big-game animals.

Did Clovis people over-hunt the huge mammals into extinction? Is there another explanation? Conclusive answers may never be found.

After the discovery of Clovis Culture, most scientists accepted the notion humans first settled the Americas no earlier than about 13,000 years ago by walking from Asia to Alaska via a land bridge. There have been countless claims of earlier humans living as long as 130,000 years ago in the Americas, but virtually all have been called into question.

Now, a new discovery may prove Clovis Man was not the first American. In the early 1930s, a trapper discovered a remarkable footprint — 22 inches long and eight inches wide — in the White Sands of New Mexico, west of the Caprock escarpment. The trapper thought he’d found evidence of the mythical Bigfoot, but research confirmed the print was that of a giant sloth.

The find spurred further excavation at White Sands. In recent years, fossilized human footprints were found at White Sands National Park. According to a September 2021 report published in the journal Science, the impressions indicate early humans occupied North America between 23,000 and 21,000 years ago, thousands of years before Clovis Man appeared, transforming views of when — and how — the continent was settled. Dating from a time scientists think massive ice sheets walled off human passage to North America, the fossils seem to prove humans were living in North America before the Last Glacial Maximum closed migration routes from Asia.

Scores of footprints of children and teenagers — and a few adults — formed by walking in soft prehistoric mud, were found near ancient Lake Otero, a 1,600-square-mile body of water that dried up about 10,000 years ago and now forms part of Alkali Flat in White Sands. Seeds from Ruppia grass, an aquatic plant, were found in sediment layers above and below the footprints.

The seeds were carbon-dated, yielding remarkably precise dates for the impressions.

"One of the reasons there is so much debate is that there is a real lack of very firm, unequivocal data points. That's what we think we probably have [at White Sands]," said Professor Matthew Bennett, an author of the study.

Anthropologists believe the footprints may have been left by youngsters helping adults with a hunting technique seen in later Native American cultures, the “buffalo jump,” involving driving large game over the edge of a cliff. Butchering of animals began immediately, and fires were started to render fat. Footprints may have been left by teens collecting firewood, water or other essentials during the processing.

The White Sands discovery calls into question not only when humans first arrived on the North American continent, but how. If people were in the Americas during the Last Glacial Maximum, did they arrive through inland routes before the glacial doors slammed shut? Did they boat around icy areas of the coasts? Such questions are the subject of ongoing research at White Sands and elsewhere.

These vestiges of the new oldest Americans were found just a couple of hundred miles southwest of the first discovery of Clovis Man, evidence the Llano Estacado was home to the earliest Americans, regardless of when or how they arrived.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: Caprock Chronicles: Footprints in the Sand: Was Clovis Man the first American?