Caprock Chronicles: Horses on the Llano Estacado in the 19th Century

Editor’s Note: Jack Becker is the editor of Caprock Chronicles and is a Librarian Emeritus from Texas Tech University. He can be reached at jack.becker@ttu.edu. Today’s article about mustangs on the Llano Estacado is by Paul Carlson, emeritus professor of history at Texas Tech.

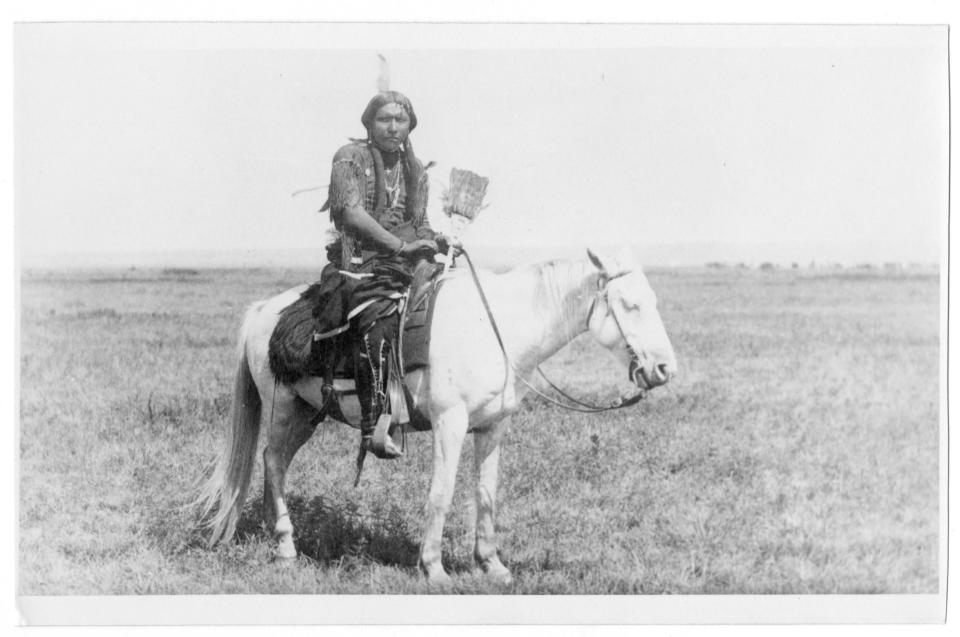

Obviously, during the 19th century, horses proved vital to humans. At the time, many horses on the Llano Estacado were half wild animals that belonged to Comanches and their allies. Others remained, as Johnny Cook, a bison hunter, wrote, “unfettered in their freedom.”

There were a lot of horses. In 1832, about the time beaver trapping in the Rockies reached its peak, Albert Pike, an adventurer, and Bill Williams, an old Mountain Man, led a group of trappers eastward from Taos and Santa Fe, across the Llano Estacado, and down Blackwater Draw.

On their journey, Pike, Williams, and the trappers encountered 3 separate Comanche villages or rancherias. The first village, located in the sandhills of Lamb County, appeared small and destitute without adequate food, clothing, or tipi coverings. Still, the little village of 20 lodges, whose men were absent in a fight with Comancheros, held over 1,000 horses, watched over by the few women and children left behind.

A second village, perhaps in the area of present McKenzie Park, looked a bit larger and far less destitute. Its men were likewise gone, probably in the same fight as those men from the first village. This Comanche band, according to Pike, likewise held a thousand horses.

The third village Pike and Williams’ group found spread farther down the Upper North Fork of the Double Mountain Fork of the Brazos River. It was well provisioned and described as having “handsome” tipis and carefully-dressed inhabitants, with at least 3,000 horses.

Because of the large number of horses they owned, Comanches moved their camps often—horses ate a lot. To meet the grazing (feeding) requirements of their mounts they shifted camp as their animals consumed the nearby grass. As a result, perhaps we should remember Comanches as mobile horse Indians more than as nomadic bison hunters. Hungry horses—more than bison herds—required Comanches to be constantly on the move.

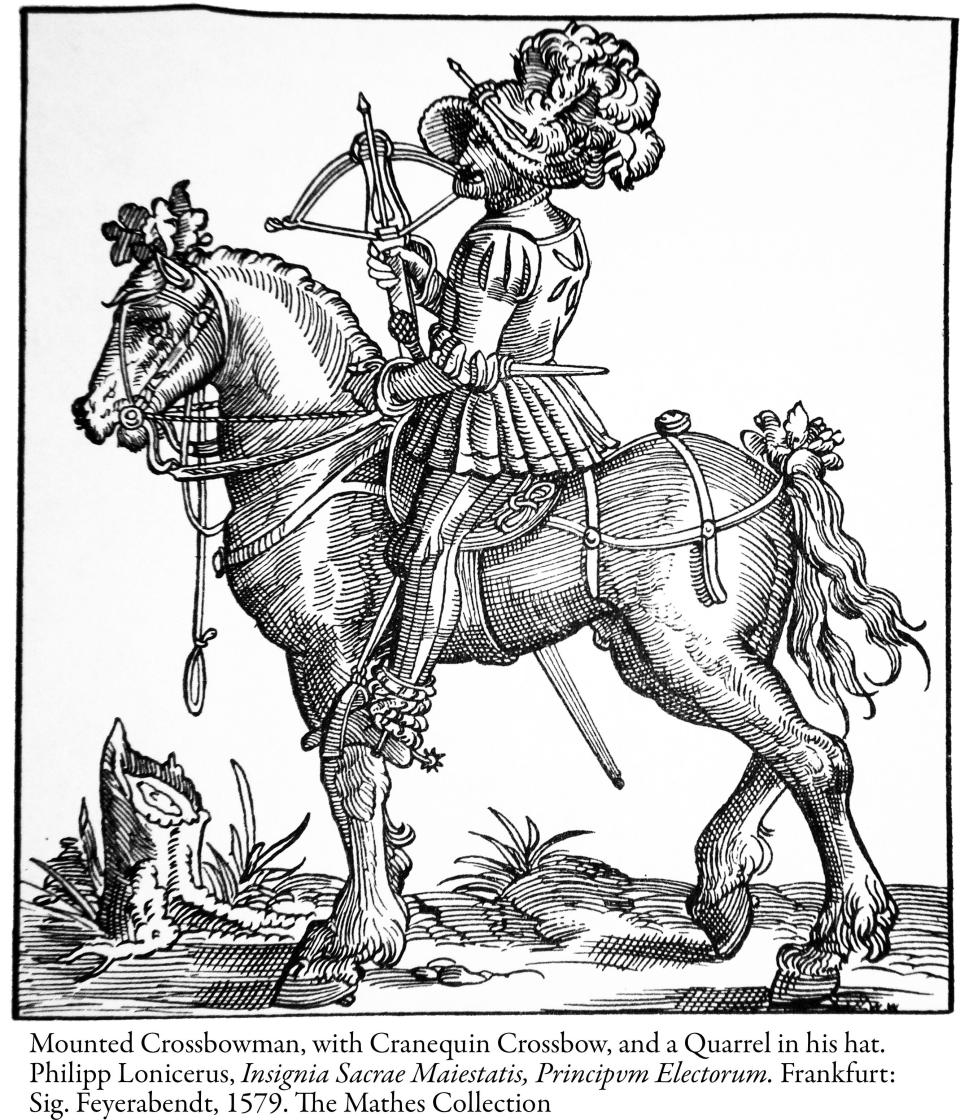

While there were a lot of horses on the Llano in the 19th century, there also existed an enormous demand for the animals. The demand increased during and after the Civil War. Comanches captured horses for themselves and for trade, especially with Northern Plains Indians, who needed horses as they lost many to cold and snow and inadequate forage each winter. Eastern Plains tribes, such as Chickasaws, Cherokees, Osages, Delawares, and Shawnees, wanted horses. too.

Demand for horses in Saint Louis, Fort Smith in Arkansas, and New Orleans, fueled by an insatiable American market, especially in the South, steadily increased.

The horse trade remained busy, and Comanches played a pivotal role in it. They acquired horses in New Mexico, raided Texas ranches for livestock, crossed into Mexico to gather horses at bordering haciendas, bred and raised their own animals, and rounded up wild horses on the Llano Estacado.

The high demand and the large number of horses attracted “mustangers,” men seeking to capture the wild animals to sell. Hispanic “mesteneros,” such as Pedro and Soledad Trujillo, came from New Mexico, and toward the end of the century such Lubbockites as Isham Tubbs with his sons William, Rob, Frank, and Lee, sought mustangs to augment their income.

According to most witnesses, wild horse herds on the Llano made an impressive sight. In May of 1849, for example, Randolph B. Marcy guided a large party of California-bound gold seekers from Fort Smith to Santa Fe.

While on the Llano near modern Vega, some New Yorkers in Marcy’s charge watched a herd of mustangs approach. One Easterner wrote: “About 3 pm we were amused by the appearance of . . . wild horses. They came within 3 hundred yards of us and stared at us with as much curiosity as we had of them.”

The horses, “after treating their eyes sufficiently and satisfied that we were the folks who hold horses as slaves,” turned about “and made quick tracks for the south.” It “was a splendid sight to look” on. As far as our “eyes could reach, we grazed after them, till they became as small pigmies.”

In July 1877, as another example, Johnny Cook and bison-hunting companion Sam Carr while searching for Comanches rode up on a large horse herd. They were in northern Martin County west of Sulphur Springs Creek and northwest of Big Spring.

They “had ascended a rise in the plain,” remembered Cook, when they saw “scattered over many thousands of acres . . . bands of wild horses.” The animals, wrote Cook, “were ranging in unmolested freedom and in perfect quiet.”

Awed by the incredible scene, the men watched the horses for hours. “As evening came on,” Cook concluded, “young colts came running and frisking around in reckless abandon in their wild unfettered freedom.”

Clearly, the horses scattered before them in their “unfettered freedom,” represented an impressive sight of the most vital animal to man in the 19th century.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: Caprock Chronicles: Horses on the Llano Estacado in the 19th Century