Caprock Chronicles: A racially charged trial in Lubbock, part two: An exceedingly speedy trial

Editor’s Note: Jack Becker is the editor of Caprock Chronicles and is a Librarian Emeritus from Texas Tech University. He can be reached at jack.becker@ttu.edu. Today’s article about the 1947 Lubbock trial of George Holland is the second of a three-part series by frequent contributor Chuck Lanehart, Lubbock attorney and award-winning history writer.

The man accused of killing the Sheriff of Crosby County on Aug. 2, 1947, was entitled to a speedy trial — guaranteed by the US and Texas Constitutions. He got one, but a speedy trial was certainly not in his best interest.

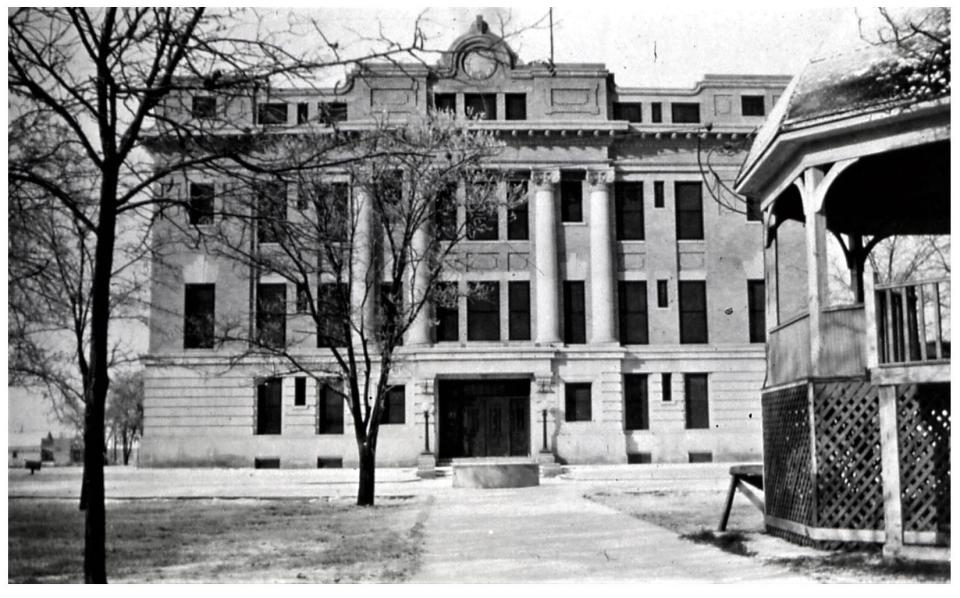

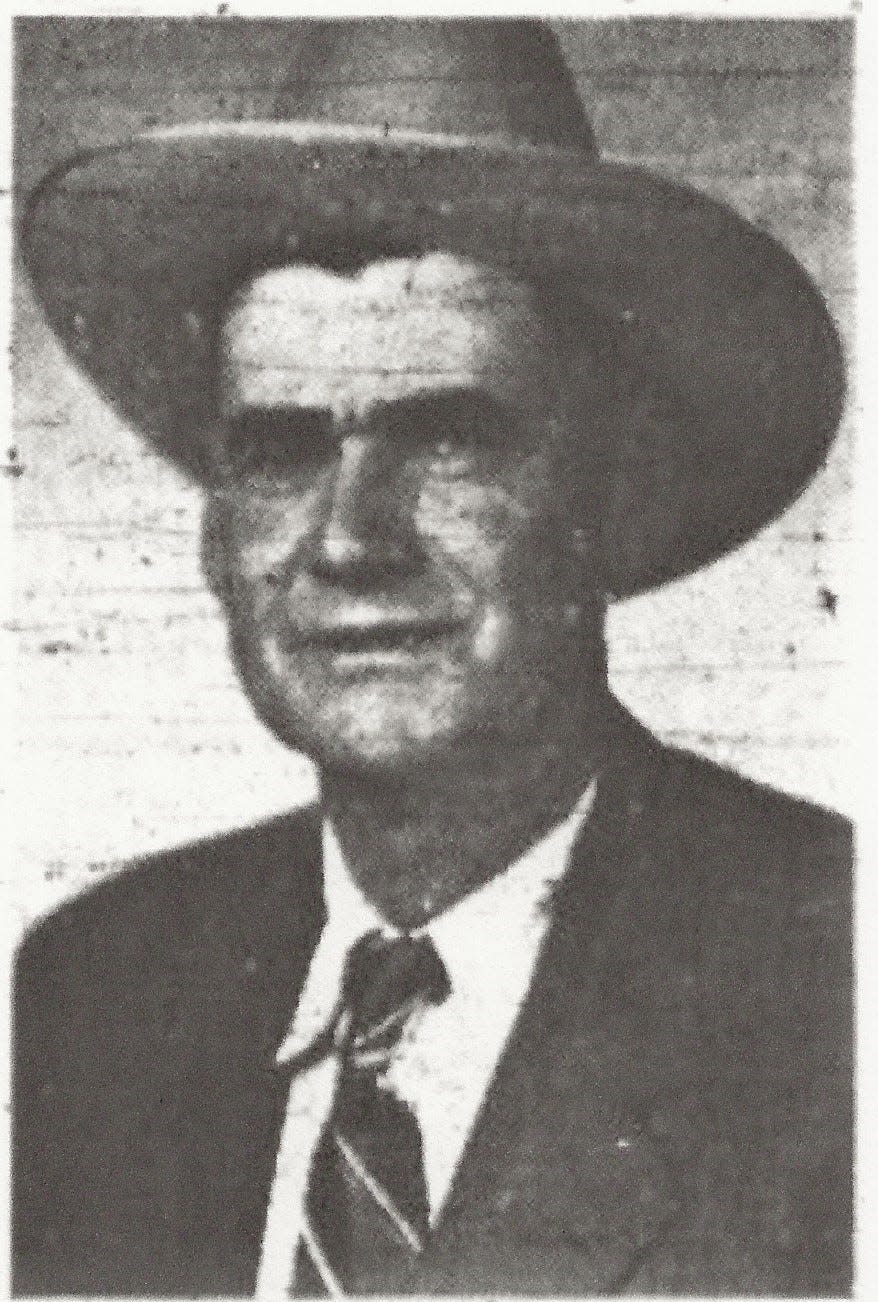

Six days following the brutal death of J.J. Pierce, George Holland was indicted for “murder with malice” by a Crosby County grand jury. It was a capital crime, and 72nd District Court Judge Dan Blair acted swiftly, moving venue to Lubbock County and scheduling a trial date of Sept. 15, just 40 days following the Sheriff’s death. Judge Blair was a former Lubbock County District Attorney.

Dismissing his court-appointed counsel, Holland hired two inexperienced Lubbock lawyers, A.C. Cooke and Bryan Dillard, as his defense attorneys. Not much is known of Cooke, except he primarily handled probate cases. Dillard was the son of one of the first Lubbock County pioneer lawyers, J.J. Dillard, who established the Lubbock Avalanche, now the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Bryan Dillard had only seven years of legal experience in 1947. Neither lawyer had practiced much criminal law.

The defense filed a motion for continuance alleging racial discrimination, because “an insufficient number of negroes had been called for jury duty in Lubbock.” The motion claimed witnesses had been intimidated, precluding the defense from being able to properly conduct an investigation. The lawyers also complained of inadequate time—15 days—to prepare for trial. Judge Blair denied the motion in short order.

More than 100 men appeared for jury service, and a dozen—all white—were quickly selected. The indictment was read, to which the defense answered, “not guilty by reason of temporary insanity and self-defense.”

The prosecution, led by District Attorney Lloyd Croslin of Lubbock, presented only a dozen witnesses. Thomas James, who operated a service station about a quarter mile from Holland’s Ralls residence, testified Sheriff Pierce came by his shop about 9:45 p.m. Aug. 2 and "left his car parked on the other side of the lot behind the building and walked off."

Lewis Flowers was in a café in the “Flats” area of Ralls when he heard a shot. He ran onto the porch and saw the flash of two additional gunshots south of the café. Suddenly, Flowers saw Holland coming from the direction of the shots, walking fast and holding his right hand to his side. He heard someone ask, “Is he shot?” Holland replied, “No, come on.” Flowers watched Holland drive away in his car, and headlights illuminated a vacant lot to the south. “In those lights, I seen a man, looked like the body of a man lying down in some weeds . . . That was the same place where I saw the gun flashes.” The body was that of Sheriff J.J. Pierce.

Other witnesses, identified as “negros” in news accounts, testified they heard five or six gunshots in the vicinity, saw Holland get into his car, and some saw a “shiny object” in Holland’s hand.

With no eye witnesses, the State’s evidence was circumstantial. Before the trial, news reports indicated Holland gave an oral confession the day after his arrest, but jurors did not hear Holland’s confession. There were also reports Holland led officers to Sheriff Pierce’s pistol, hidden under a pile of trash with five empty shells. However, the weapon was not introduced into evidence, and there was no forensic evidence to prove the pistol was in fact the murder weapon.

The prosecution rested its case on the afternoon of the second day of trial, and the defense rested without producing any evidence. In final arguments, DA Croslin asked for a conviction and the death penalty. It took the jury only 75 minutes to agree.

“Death for Negro” read the prominent front-page headline of the September 17, 1947 Lubbock Evening Journal, and similar headlines throughout Texas and beyond identified George Holland only by his race.

On Dec. 5, the court heard a defense motion for a new trial. Joining the defense team to litigate the motion was 42-year-old Dallas attorney W.J. Durham, a graduate of the University of Kansas School of Law who had also studied at Harvard University. Newspapers reported it was “the first time a negro lawyer had appeared” in a Lubbock County case. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People retained him to assist on Holland’s behalf.

Durham led Holland’s defense at the hearing, expanding on claims made before trial in the defense motion for continuance. Witnesses said DA Croslin and another officer “whipped and otherwise intimidated negro witnesses soon after the slaying,” claiming racial discrimination and jury misconduct. They also presented medical testimony that Holland suffered a brain injury that “affected his social responsibility.”

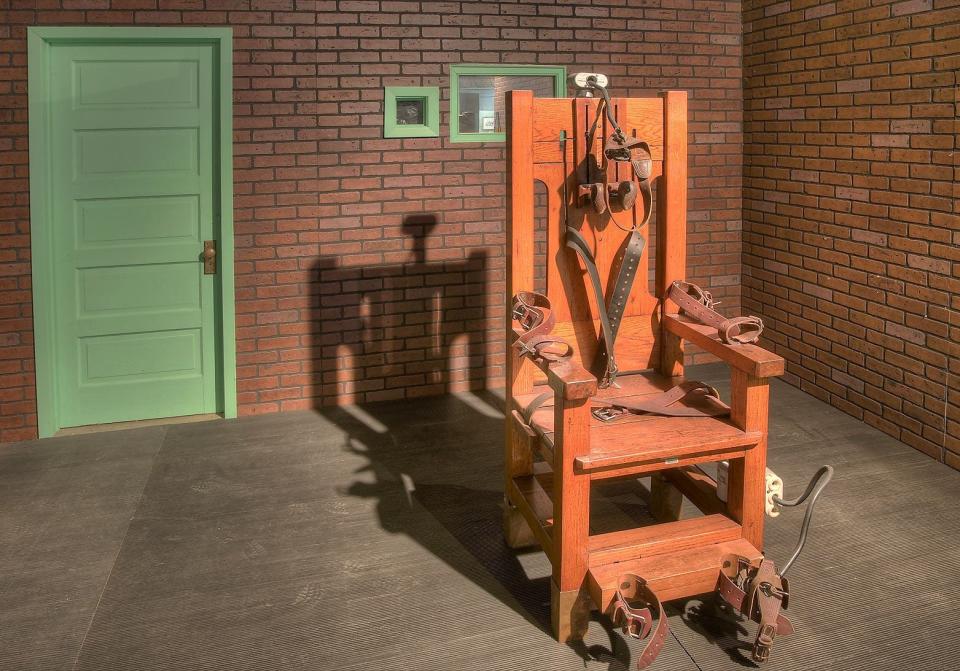

When arguments concluded, Judge Blair ruled, simply, “The motion of George Holland for a new trial will be overruled.” The “negro” was dispatched to await Old Sparky in Huntsville.

Part Three of this series will be published in next Sunday’s Lubbock AJ.

Suggested photo captions:

Crosby County Sheriff J.J. Pierce, circa 1946. Lubbock Avalanche-Journal archives.

The stately 1916 Lubbock County Courthouse was the site of the 1947 George Holland capital murder trial. Photo courtesy of the Southwest Collection, Texas Tech University.

“Old Sparky,” on Texas’ Death Row, where George Holland was sent to be executed. Photo courtesy of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: Caprock Chronicles: A racially charged trial in Lubbock, part two: An exceedingly speedy trial