Caprock Chronicles: Rodeos in the skies

Editors Note: Caprock Chronicles are edited each week by Jack Becker, Librarian Emeritus, TTU Libraries. He can be reached at jack.becker@ttu.edu. Today’s article is by contributor, Amy Von Lintel.

The human conquest of the air by flight began around 1799 with the invention of the hot air balloon in France, while aviation by plane was possible starting in 1903.

Historian Jason Weems refers to this shift as “aeriality” or the “process of aerial seeing, picturing and thinking.” Aeriality included seeing Paris from a balloon, but also seeing the flat West Texas geometric grids of fenced ranches and fields of crops from high above, or the massive Palo Duro Canyon as a mere scar in the earth. It comprised not just the sensation of being elevated, but also new senses of motion — the body moving up and down, right and left, and even swoops and loops — a transformative experience for pilots and passengers alike in the era of barnstorming.

But these new sensations were not limited to trick pilots and planes, especially in our sprawling rural region. Ranchers, cowboys, doctors, veterinarians — men and women alike maneuvered through the skies for both business and pleasure, starting in the late 1920s.

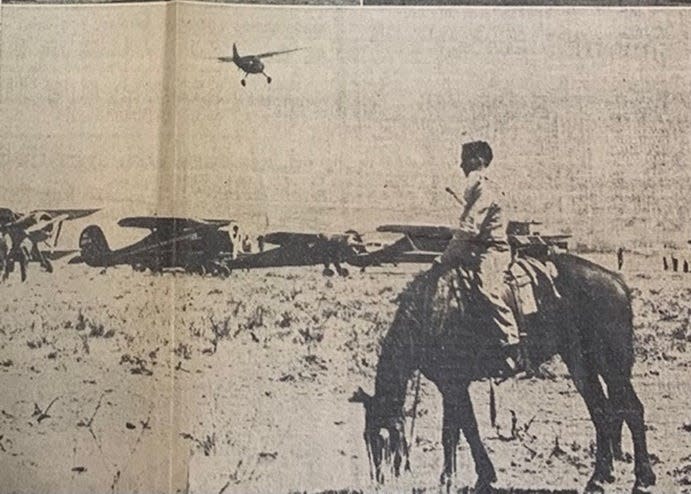

For example, an extant photograph captured one rancher herding cattle from his plane. To be sure, “cowboying” from privately owned planes became a common thing in the region, both as a functional part of the ranching lifestyle and as a spectator sport. In his memoir Pioneer Pilot from the Texas Panhandle: Stories of a Flier’s Life, George Christopher described barnstorming demonstrations where pilots would “bulldog a steer from the wing of a plane” in front of crowds of people. According to Christopher, a cowboy on a horse would direct the steer as the pilot swooped down.

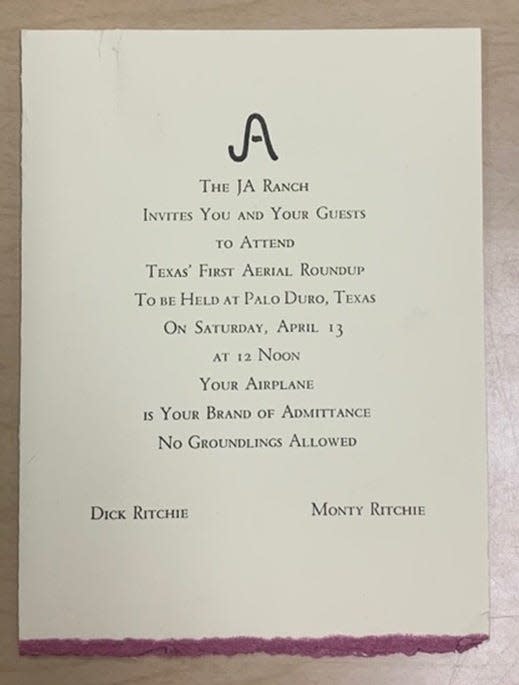

The cowboy-pilot gained an important place in Panhandle history, just as cattle ranches become their own centers of aviation. In 1940, the JA Ranch was the location of an extravagant aviation event. On April 13, the brothers Monte and Dick Ritchie hosted the First Aerial Roundup. As the invitation declared, the guests’ airplanes were to be their “brand of admittance” and no “groundlings” were “allowed.”

One hundred and two planes landed on the three 3000-foot ranch runways “graded and manicured to a king’s taste” for the event, bringing 205 attendees. The Ritchie brothers arranged for evening parking of the planes at English Field in Amarillo, and for transportation of their attendees to the luxurious Herring Hotel for a happy hour followed by a banquet with dancing. The invitation even promised “a date bureau available for unattached pilots”.

Journalist Dick Martin described the Aerial Roundup: “From far and near they came—big planes, little planes, single engine planes, twin-engined planes, new planes, old planes, shiny planes and dull veteran planes. All came roaring over the field, swung into the wind, and touched their wheels to the runway in rapid order.” Martin witnessed fifteen planes at once “circling above in a giant pinwheel … that “filled the heavens with thunder.” The visual and auditory aspects of the Roundup were awe-inspiring for those present.

We must return to the archives to help us recall the practice of cowboying from planes. The invitation — now preserved in the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum — played upon nostalgia for the “good ole’ days” of cowboys and cattle but emphasized that this “Old West” experience was attainable only by airplane — “no groundlings allowed.” Tours of the “half million acres of the JA and its 25,000 head of cattle” were offered from the air during the Roundup, which “cowboys [would] be glad to conduct.”

The invitation continued: “We feel it’s a tribute to the advancement of aviation that an aerial roundup has replaced the traditional rodeo.

A 1938 article in the Clovis (NM) News Journal argued that the modern cowboy was a pilot: “The cowboy’s top horse today is an airplane. This ‘old faithful’ of the modern ranch rounds up wild horses, locates the stray calves, rides fences, brings buyers, rushes emergency supplies and, when business is done, takes the owner out for diversion.”

The author described how “plenty of young fellows will leap at the chance to be a cow pilot” and how “flying is a valuable aid to the man whose wealth is scattered through those nooks and crannies” when it is “no small responsibility keeping track of so much territory, so many cowhands, such big herds.” Planes could deliver supplies quickly, could find a “stray in the snow,” could drop feed from above, and could reach places even when roads were impassable.

What we learn in returning to these documents is just how strategic and central the airplane has been to the identity and development of our region.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: Caprock Chronicles: Rodeos in the skies