Caprock Chronicles: The Sharps rifle, buffalo hunting, and the South Plains

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor’s note: Jack Becker is the editor of Caprock Chronicles. He is a Librarian Emeritus, Texas Tech University Libraries. He can be reached at jack.becker@ttu.edu. Today’s essay is about the Sharps Rifle and its use by buffalo hunters on the South Plains was written by Austin Allison, Assistant Librarian and Cataloger, Southwest Collection/Special Collection Library at TTU.

Several prominent names are associated with American firearm development during the 19th century: Oliver Winchester, Eliphalet Remington, Jacob and Samuel Hawken, Melchior Fordney, and Christian Sharps to name a few. The lesser known of these gunsmiths was Christian Sharps.

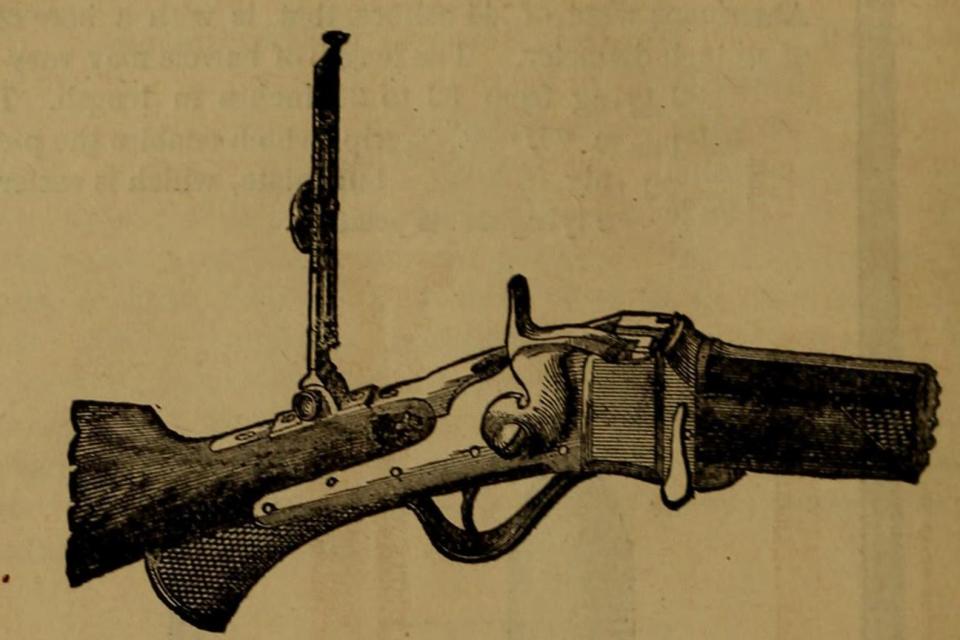

Dating to 1848, the Sharps rifle and its patented breech-loading, falling block design was a go-to firearm for snipers and long-distance shooters due to its accuracy and ease of use. Christian Sharps left the enterprise in the 1850s and the company moved to Connecticut, but the Sharps Rifle Company carried on using his name to market rifles for the next several decades.

Texas Senator Thomas Jefferson Rusk touted the new style rifle in an 1848 newspaper article noting that the rifle was “the most convenient and fatal weapon ever used.” This early model was capable of carrying 50 percussion caps at a time, which made it possible for a rifleman to shoot at a much more rapid rate than previously possible. It was the most popular carbine rifle during the Civil War, and it saw use for a significant amount of time following the war.

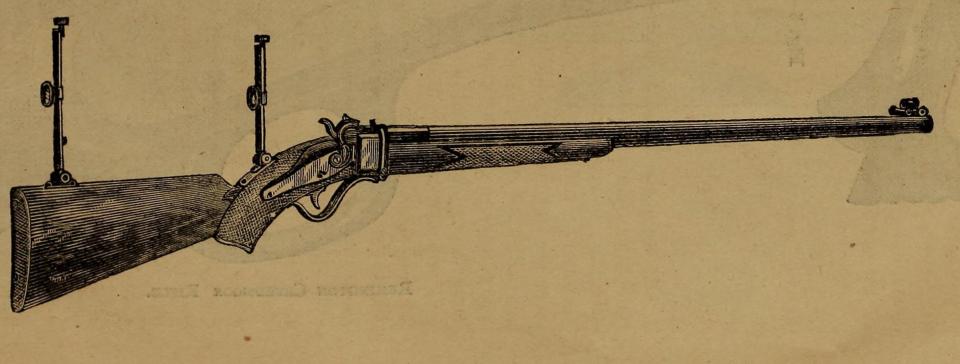

The Model 1874 Sharps, which actually entered production in 1871, introduced the capability of the rifle to be chambered in a variety of calibers. The most prominent of these cartridges was the .45-70 (pronounced “forty five seventy”), but common chamberings in 45 caliber included .45-70, .45-90, .45-110, and even a .45-120 offering that came into production in the late 1870s or early 1880s. 40, 44 and 50 caliber options were also available, along with options for barrel length.

Christian Sharps died in 1874 having left the company two decades prior, but the impact of his rifle was just becoming fully realized at his death with the advent of the Model 1874 version of the rifle.

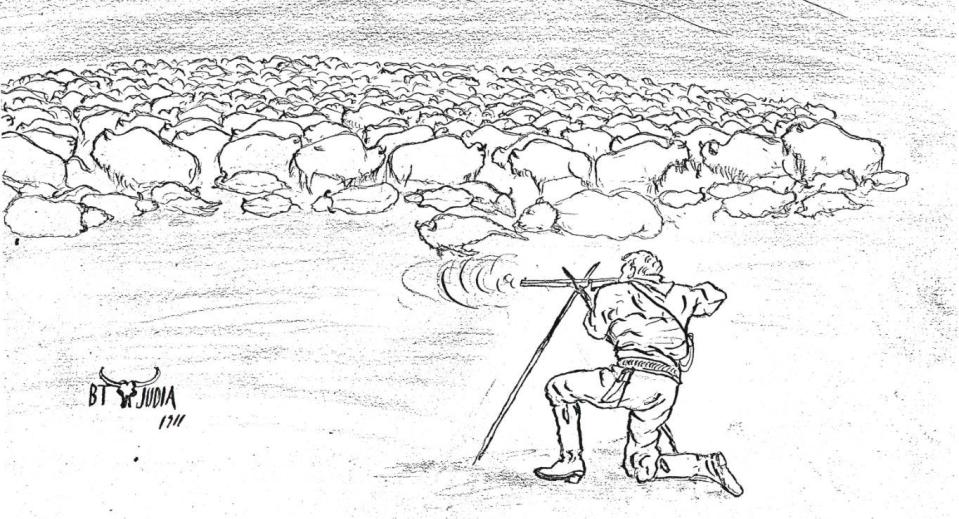

The 1870s saw the decimation of American buffalo herds on the Great Plains, one of which was prevalent on the southern plains of Texas. Buffalo hunters flooded the region in the 1870s influenced by forces in the eastern United States that desired not only buffalo pelts but also the forced submission of Native Americans to relocate on to reservations.

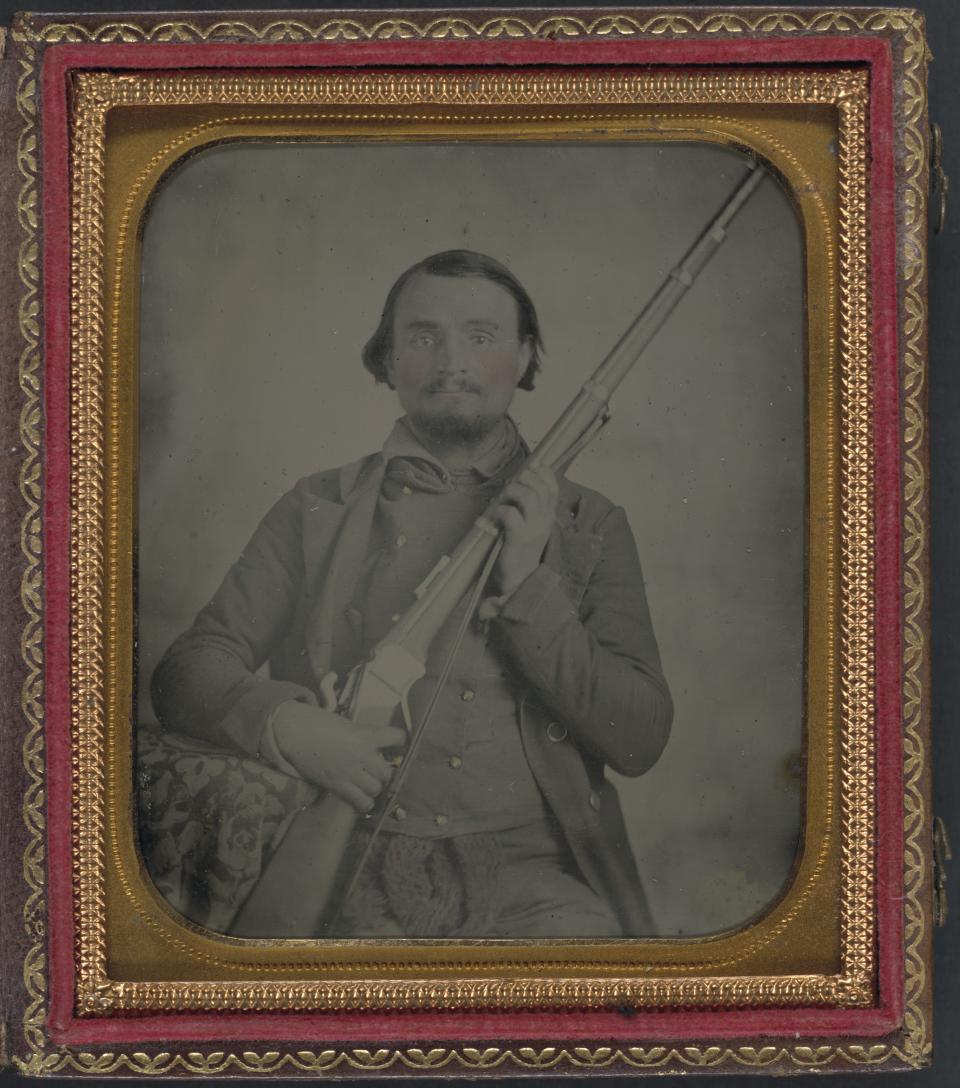

Written accounts of buffalo hunting on the plains consistently mention the abundant use of Sharps rifles. One such account is that of John R. Cook in his book The Border and the Buffalo. Cook spent a significant amount of time in Texas in the mid-1870s hunting buffalo in areas ranging between as far north as Fort Elliott in the eastern Texas panhandle to Fort Griffin and areas near the Double Mountain Fork Brazos River. Cook was most well-known for his recollection of buffalo hunter and United States Army skirmishes with the Comanche in 1877.

Cook mentioned possessing a Creedmoor 45 Sharps that he purchased at Fort Elliott in 1876, but he also mentions other hunters having Sharps rifles. Marshall Sewall, a hunter who was killed on Deep Creek in Scurry County in February 1877, also carried a variant of the rifle, which fell into the hands of the marauding Comanche. Cook notes that the Comanche felt that this gun was cursed due to injuries and deaths that befell tribe members who used that particular gun in the following weeks. They eventually buried the gun in some sandhills, after having adorned it with the scalp they took from Sewall in February.

One of the defining features of later Sharps rifles was the advent of long-distance, ladder-style sights, often called Creedmoor, Soule, Tang, or Vernier sights that allowed shooters to adjust for elevation and windage when shooting at targets well over 400 yards or more. Cook mentions these Creedmoor sights and his ability to shoot buffalo 300 yards distant. The use of these sights allowed buffalo hunters on the plains to remain comfortable distances away from the animals that were prone to stampeding.

Texas Tech University’s Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library is home to a small, digitized collection of letters sent to the Sharps Rifle Company in Hartford, Connecticut. The bulk of these letters originated from Texas and largely consist of orders for custom rifles, bullet molds, or parts to service or repair guns. Frank E. Conrad, a retailer from Fort Griffin, sent the Sharps company a letter in February 1880 requesting six custom 40-caliber rifles with American Walnut stocks, 26 inch barrels, and single triggers. Even on the frontier of Texas, the Sharps Rifle Company’s decades-long reputation made them a reliable source for mail-order rifles that customers across the nation sent superior products to the frontier on a large scale.

The company went out of business in the early 1880s, but the legacy of the rifle company persists with modern replicas available through a variety of gunsmiths with even more custom options available than available in the 19th century. These rifles remain a mainstay at shooting competitions and gun ranges.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: Caprock Chronicles: The Sharps rifle, buffalo hunting, and the South Plains