From caravans to influencers, Asian American groups get creative on census

Maggie Miao is known for her YouTube videos teaching Mandarin speakers everyday English. Her own struggles ordering a Starbucks coffee at an airport when she arrived in the United States from China for graduate school in 2013 pushed her to launch Maaaxter English, a YouTube channel that now has more than half a million subscribers.

Miao is still pumping out that content, though now she’s also teaching her audience vocabulary like “canvassing” and “enumerator.”

It’s not everyday English, but they are words connected to something that touches everyday life in America — the census.

“I think that if everybody knows how important it is and how it can affect everyone's lives, they will definitely participate,” Miao, who was enlisted to make the video by TDW+Co, the official Asian American outreach and communications partner of the 2020 census, told NBC Asian America.

Leaning on social media influencers like Miao is just one of the creative ways Asian American groups across the country are working to ensure everyone in their hard-to-count communities completes the 2020 census as the deadline to do so fast approaches.

It’s a task made more urgent after traditional outreach efforts early on, like door knocking and face-to-face contact, were hobbled by the Covid-19 crisis — and after the Census Bureau announced that counting efforts would be completed by Sept. 30, an entire month earlier than planned. (A federal judge on Thursday reversed that decision, ordering that the count continue through the end of October, saying a shortened schedule most likely would produce inaccurate results.)

The once-a-decade head count of every U.S. resident is used to help decide the number of seats awarded to each state in the House of Representatives, the way representative boundaries are drawn, and how $1.5 trillion in federal funding is distributed.

It’s also used to determine which states and counties are required to provide voter language assistance according to the Voting Rights Act.

Asian American advocacy groups worry that the pandemic — combined with the confusion over the collection deadline and the tumult of a presidential campaign — could cause an undercount in a community that makes up 5.6 percent of the nation’s population.

And with the census conducted only once every 10 years, communities would be stuck with those inaccurate results for the next decade.

“We’re going to end up probably in a similar position where we will still have an undercount in some of our neighborhoods, just like in 2010, just like in 2000,” said Howard Shih, research and policy director at the Asian American Federation, a nonprofit based in New York City.

“Fingers crossed, I’m hoping that it’s not any worse than it was in previous years,” he said.

For its part, the bureau has sent out enumerators, or census takers, to households that did not respond to the survey. Their work is set to wrap up by Sept. 30 as well. Census data for New York state showed that, as of Tuesday, 96.3 percent of people had been counted, either by responding on their own or by enumerators.

New York City checked in with a 60.2 percent census self-response rate as of Tuesday, a little shy of the 2010 rate of 64 percent, according to Census Bureau data.

A separate Asian American Federation analysis found that as of Sept. 14, census tracts in which Asians made up a majority in the city’s five boroughs had an average response rate of 60.6 percent.

But certain areas with large Asian American populations lagged behind.

Richmond Hill in Queens, a borough hit hard by Covid-19, clocked only a 50 percent response rate, one of the lowest among Asian American communities, the report said. The neighborhood is home to a densely populated Indian and Indo-Caribbean community.

Clara J. Park, census program manager at the Asian American Federation, attributed those numbers to a lack of trust in government and a fear that information recorded in the census would not remain confidential, as it’s supposed to.

“It’s difficult to get over that hurdle,” Park said.

Quickly showing community members how the census affects daily life is crucial to persuading them to complete the survey, Shih and Park said. That includes connecting it to everything from how federal funds are awarded to communities for services critical to schools, to how money is allocated for programs like Medicaid and food stamps.

To spur participation, Asian Americans in Richmond Hill who filled out the census were given gift cards to local shops and restaurants, Park said. That campaign also came to Flushing, Queens, home to a large Chinese and Korean American population.

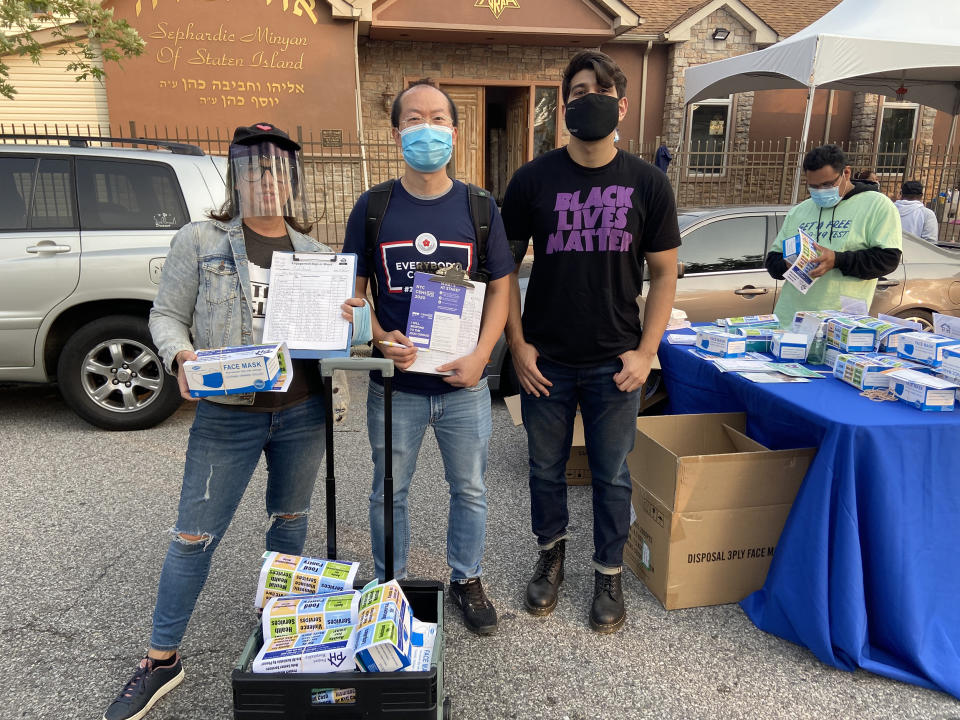

In Brooklyn, where Asian majority tracts had a mere 51 percent average response rate, a car caravan festooned with balloons and banners promoted the census in early September with a drive through Sunset Park, where many Chinese immigrants live, according to Park.

Census workers and local community group volunteers were on hand to help curious residents complete the survey, as masks and hand sanitizer were given out.

In Manhattan’s Chinatown, a bike caravan in a similar vein is planned for the end of September.

In large part, the funding that makes the outreach work possible comes from private foundations, Shih said.

“It’s crunch time right now,” Shih said as many groups, including theirs, make their final push to amp up census response rates.

Similar efforts are underway in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Adrienne Pon, executive director of the Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs for the city and county of San Francisco, said they’ve seen mixed participation in the census among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, with lower response rates in areas hammered by Covid-19.

San Francisco had a 65.6 percent self-response rate, slightly lower than its 2010 rate of 68.5 percent, according to data from the Census Bureau on Tuesday.

Just like New York, San Francisco saw its face-to-face outreach halted by the pandemic, forcing community groups to rely on phone banking, text messaging and digital platforms.

“It was a perfect storm of everything that could go wrong on top of a double pandemic, Covid-19 and protests against racism and brutality,” Pon said.

But with the collection deadline drawing near, and as some Covid-19 restrictions loosen, community-based groups are doing double time to boost response rates among San Francisco’s Asian American and Pacific Islander population, Pon said.

There have been giveaways, outdoor picnics in Japantown’s Peace Plaza, and a week of action starting Thursday, with events throughout the city to help residents with the survey.

Pon also said the city had partnered with Art + Action, a group of artists primarily based in San Francisco who in January unveiled its “Come to Your Census, S.F.” campaign.

Their artwork has been displayed on billboards, kiosks and transit shelter posters throughout San Francisco in English, Chinese, Spanish and Tagalog. The campaign has since gone national.

Pon underscored the importance of taking novel approaches to census outreach.

“What you have to do is bring the census to the people,” Pon said. “You have to make it meaningful for them.”

Tim Wang, founder and principal of TDW+Co, said that despite achieving a great turnout with the census thus far, there are still households across the country yet to be counted.

“We are in the final days to make sure that everyone in our community is counted,” he wrote in an email. “It matters now, and it matters for the next 10 years.”