The Caretta Research Project celebrates 50 years of loggerhead conservation on Wassaw Island

Editor's note: This story is the first installment in a series about loggerhead conservation on Wassaw Island.

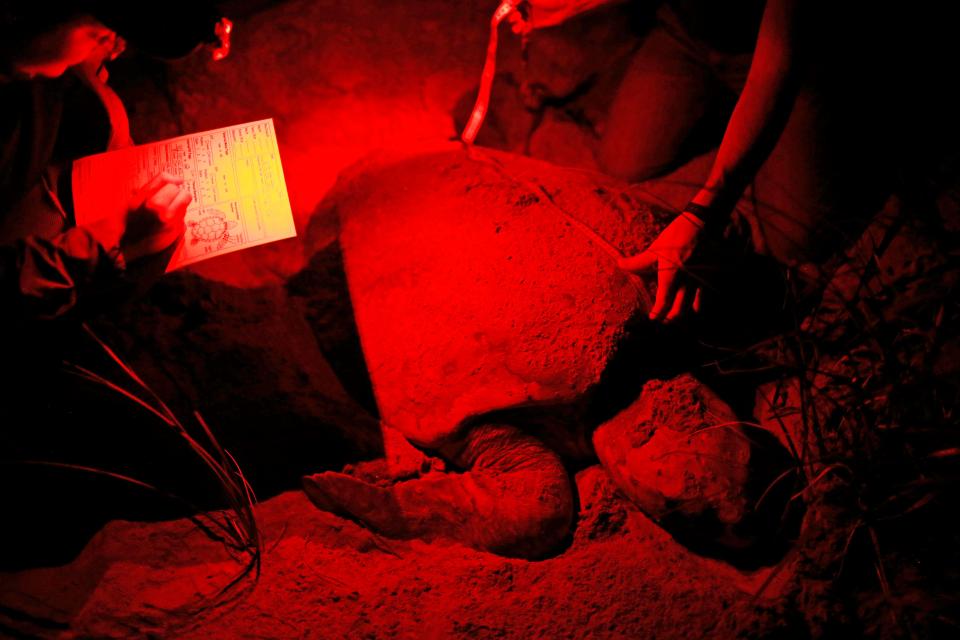

Under the haze of red-light headlamps, volunteers on Wassaw Island worked quickly and nimbly to protect the island’s latest guests – hundreds of loggerhead sea turtle eggs.

It was off to the races Wednesday night once the sun set over Georgia’s barrier islands. Volunteers on utility ATVs headed for the beach and hardly had turned off the trail and onto the sand before encountering their first loggerhead of the night. The other groups continue on to patrol up and down 7 miles of Wassaw’s coastline, stopping and starting and circling back to intercept the turtles before they disappear back into the ocean.

Turtle caretaker: Addy taught 'hundreds of thousands' about loggerheads and marine debris

Read more: Oglethorpe Charter middle school students experience Ossabaw Island as interactive classroom

Conservation worked

It hasn’t always been so busy for the Caretta Research Project’s team. According to CRP Research Director Joe Pfaller, when the project first began in the 1970s, most evenings volunteers would wait around all night for turtles to swim ashore. It was painstaking and often dull work, walking up and down the barren coastline hoping to see anything.

Nowadays, they’re much busier because those early conservation efforts worked.

“We are grateful that these early pioneers had the foresight to start these conservation practices back then, as they are the reason that we are seeing this increase in turtles today,” said Caretta Research Project Director Kris Williams, who also extended her thanks to the Wassaw Island Trust and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The Caretta Research Project is a nonprofit research, conservation and education program studying and protecting Loggerhead sea turtles at the Wassaw National Wildlife Refuge. The project celebrates its 50th anniversary this summer.

Early beginnings

Started in the 1970s by Jerry Williamson of the Savannah Science Museum, Charlie Milmine from the Wassaw Island Trust as well as the museum, and staff from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the project gets its name from loggerheads’ scientific name: Caretta caretta.

It takes about 30 years or more for loggerheads to reach sexual maturity, said Williams, and it’s only been in the last 12 to 15 years that the Caretta Research Project has started to see a significant increase in nesting activity and more individual turtles.

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, projects like CRP started cropping up on places like Jekyll Island and Little Cumberland Island, Pfaller said. Those efforts got underway when many noticed that turtle nests stopped producing as many hatchlings. More dramatically at about the same time, seemingly healthy mature loggerheads started washing up ashore dead due to drowning in shrimp trawlers.

Thanks to conservation efforts, those instances have grown increasingly rare.

Playing a long game

When the Savannah Science Museum closed in 1997, Pfaller said money and resources were tight for a couple of years while CRP continued its work. But the organization kept its faith. By the late 1990s, he said researchers knew that if they wanted to see a real turnaround they needed 30 or 40 years of consistent nest protections by conservation groups and volunteers each summer.

Late Wednesday into early Thursday, Pfaller drives along the beach, keeping his eyes peeled for turtle tracks. Crossing the beach headed toward the dunes, turtles leave distinctive flipper-carved trails. After years of practice, he can see where a turtle has stopped and started digging, or “body pitting,” to create a spot to lay eggs by using their flexible flippers to dig holes often well more than a foot deep.

Volunteers are key

Approaching a loggerhead, one volunteer waives a PIT tag scanner over the turtle’s front, left flipper. Just like the microchips veterinarians put in dogs and cats, the PIT tag reads an ID number for the turtle, which another volunteer dutifully writes down on a form.

Sometimes, the PIT scanner finds nothing. After looking for metal tags on each flipper as well, they conclude the turtle is a neophyte – that hasn’t yet been documented, and is possibly laying its very first clutch of eggs in its life. In this case, Pfaller inserts a PIT tag and adds tags to each flipper for future researchers to identify the turtle and add to its documentation.

Volunteers don’t collect information or samples while the turtle is preparing or actively laying eggs so as not to disturb the process, although once the turtle is laying eggs it enters a focused trance and doesn’t mind the people standing nearby. It hardly seems to notice when a hand reaches underneath its rear and into the nest to select an egg for research. Every now and then, the mother loggerhead will heave a heavy sigh.

Because they don’t want to disrupt a nesting turtle, CRP’s team is often collecting data on the move while the turtle is lumbering up the beach or returning to the water.

Moving like a NASCAR pit crew, a small team works quickly and in unison completing separate tasks: measuring shell dimensions, recording the time and location, and reading off tag numbers. One person walks to the side, clipboard in hand, jotting down records that will be logged to a shared database for loggerhead conservation groups. Pfaller and Williams, given their experience and expertise, collect non-invasive skin samples to send off to research labs at the University of Georgia and the University of Florida.

Instinctual

“Everything about what (the mother loggerhead) is doing is instinct,” Pfaller said. Despite the numerous time he’s watched the nesting process, he marvels that these turtles have no instruction on how to nest correctly from their parents and no way of knowing if they are successful. But like clockwork, they return to nest each couple of years.

Sometimes the loggerheads nest in poor places, such as too close to the water where the tide will wipe out the nest and possibly kill the eggs. Part of CRP’s work during the night is digging up these nests and placing them in a newly dug hole in a safer location.

Each nest can contain about 120 eggs, and female loggerheads can lay around three to five clutches in a season. After reaching sexual maturity, they rotate between spending three to four years out in the open ocean and returning to nest, although they don’t always nest on the same beach, or even island. Using a ledger of the PIT tag numbers and numbers from tags placed on each front flipper, volunteers can identify the turtle and see where it has been documented before, often nearby nesting sites such as Hilton Head, Ossabaw, Jekyll or beyond.

At around 3 a.m. the tide has lowered for the night, and the number of turtles pushing themselves up the beach trickles to a stop. With all the nests covered with staked-down mesh and fencing for protection from racoons, rattlesnakes and other predators, the patrol groups drive up and down their sections a few more times before calling it a night, although some will go again in just a few hours at dawn to catch an uncommon dawn-nesting turtle. Back at the staff cabin, Pfaller and a summer intern sit down to begin the tedious work on logging data into their computers.

Data collection

While conservationists around the world have been tagging turtles since the 1960s and 1970s, a lot of the recorded data on loggerheads is relatively new. It wasn’t until the mid-2000s that CRP has been sampling DNA to learn more about where the turtles were born, where they went to lay eggs and even where they’ve been feeding. The advent of seaturtle.org, a website in which groups like CRP log their data, has helped globalize and make accessible a wealth of shared data on sea turtles.

CRP’s sustainability isn’t just in turtle populations and continuing a longitudinal study of Wassaw’s nesting turtles. Part of continuing the growing turtle population has to do with people. Volunteers are all ages, ranging from teenagers to graduate researchers to senior citizens.

“Most people that come out have never seen a turtle before, and never stayed up all night on the beach before, have never slept during the day in 95-degree heat and endured some really bad insects that we can have on the Georgia coast,” Pfaller said.

"I've just loved learning all about them," said Ellie Rauls, a teen volunteer who came from Ohio. Standing by a nest site, she pointed out some of her favorite parts, like how the turtles are so adept at using their flippers to dig such deep holes.

But once they’ve gotten some training, by the end of a week’s stay they have learned lots. Not only have they learned plenty about loggerheads, but they’ll walk away with experience logging scientific data and completing fieldwork. Many volunteers come back year after year.

CRP also uses donations to fund a scholarship for students to volunteer and do additional work for the program to gain field experience. Additionally, each summer they take on an intern — this year Kegan Kurinij, a University of Georgia undergraduate who has volunteered with the program before.

Plenty of volunteers are inspired by the work they complete on Wassau. Pfaller should know — he started volunteering when he was only 15 years old and was Williams’ intern back in 1998. He then went to school, studied and researched turtles, and has been serving as CRP’s research director since 2011.

CRP also fosters continuing, sustainable conservation efforts by partnering with academic researchers, government agencies, and local shrimp trawlers and fishermen. Whether it’s encouraging the use of turtle exclusion devices, which help fishers keep turtles out of their nets, or organizing for them to stay away from the beaches during nesting season, CRP’s outreach extends beyond the beach to open dialogue with much larger communities.

CRP’s summer nesting season kicks off the Saturday before May 10 each year and lasts 17 weeks, closing the Saturday before Labor Day. By June 1, Pfaller said they had seen about 88 nests. Since 1973, CRP reports that nesting on Wassau has increased more than eight-fold.

According to Pfaller, even in the mid-2000s, CRP was seeing 60 to 80, maybe 100 loggerhead nests a year. In 2019, Wausau had 280 nests and is projected to have at least that number or more in 2022.

Marisa Mecke is an environmental journalist covering climate change and the environment. She can be reached at mmecke@gannett.com or by phone at (912) 328-4411.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Wassaw Island loggerhead turtles: Group marks 50 years of conservation