Carolina de Robertis On Familial Homophobia: Not Everyone Comes Around

For many years, Carolina de Robertis didn't talk about being disowned by her parents. It was a relatively slow-moving process, beginning at 19 when she first put words to her queerness and culminating six years later when she met the woman she would eventually marry and thought, "This is the love of my life." Her parents responded by cutting ties and trying to turn her siblings against her and her children.

Talking, at least publicly, about her parents proved challenging. "I would get hit with xenophobia and anti-Latinx bias. Anti-Latinx stereotypes would come at me almost immediately," says de Robertis, the author of the international bestseller, The Invisible Mountain. "I would say, 'Well, my parents disowned me for being gay.' And people would say, 'That's because they're Latinos and they're Latino immigrants and so they don't understand. You come from a backwards people.' And all of that is not true."

The more time de Robertis spent in Uruguay, the more that she got to know the people there, her people, the more she came to appreciate just how accepting and progressive the country is. In other words, the search for queer life in Uruguay was a wild success: De Robertis found that her parents "are much more homophobic than their country of origin" and perhaps most importantly for a devoted reader like me, that personal journey became the genesis of Cantoras, one of my favorite novels in recent memory. Against the many obstacles faced living under Uruguay's oppressive dictatorship in the 1970s, the five queer women at the heart of Cantoras still find a way to create a community, a family. As best they can, they find a way to thrive.

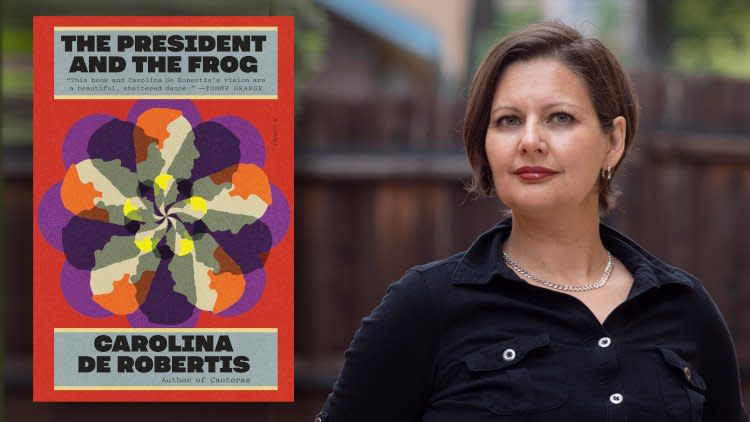

Now Carolina de Robertis is back with her fifth novel, The President and The Frog, a quiet and thrilling portrait of hope, loosely based on the 12-year imprisonment that José Mujica endured before his remarkable ascent to the presidency. To celebrate the release of The President and The Drog, de Robertis sat down with the LGBTQ&A podcast to talk about the new novel, having to continually redefine what "home" means to her, and what we're missing when we talk about familial homophobia.

"If we all wait for all the homophobic people to come around, we're going to give up our whole lives. For me, having kids really rooted me in that."

You can read an excerpt below and listen to the full interview on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Jeffrey Masters: While your mother was pregnant with you, your family immigrated from Uruguay to England, then to Switzerland, and eventually California. What is it about Uruguay that keeps calling you back to it in your writing?

Carolina de Robertis: I think there's various layers to that. One of them for me is that I have this peculiar experience of remembering immigrating to this country at 10 years old. So I'm not a daughter of immigrants who were born here, unlike other people who sort of have this experience of having been fully formed in the United States.

But I also didn't grow up in or wasn't born in my country of origin. I have this distance of not having been shaped within the country of origin as immigrants who come directly from their country to the United States have that memory and that proximity to the culture. So I was living in different countries where I always felt like I had this country inside of my skin that wasn't visible to me outside my skin. I think there's that kind of pull and fascination born of distance and a sense of there being a rootedness that is elsewhere.

When my parents disowned me in my mid-twenties, due to various things including familial homophobia combined with this idea that I couldn't be Uruguayan, my parents explicitly said that to me, "You can't be Uruguayan anymore because you're gay. That doesn't exist in our country." So, of course, what does that do? It launches me on this deep journey to reclaim my roots on my own terms.

JM: I think it’s important you do talk about being disowned because it's easy to think that doesn't happen to people anymore.

CDR: When I was launching my first and second book, I really couldn't talk about it in public. The main reason was that I would get hit with xenophobia and anti-Latinx bias. Anti-Latinx stereotypes would come at me almost immediately.

I would say, "Well, my parents disowned me for being gay." And people would say, "That's because they're Latinos and they're Latino immigrants and so they don't understand. You come from a backwards people." And all of that is not true.

I went back to Uruguay and not only did my search for lesbian life succeed and lead to the seeds to Cantoras, this novel about lesbians during the dictatorship in Uruguay, but also I found that Uruguay, in particular, is the most secular country in Latin America. It's very progressive. And I found a lot of relative openness. My parents are much more homophobic than their country of origin.

In fact, I think Latinx culture today is in some ways on the vanguard of queer culture-making as evidenced even by the x and Latinx or the e in Latine, in Spanish-speaking contexts.

JM: When your parents ended their relationship with you, how old were you and how long had you been out of the closet?

CDR: I was 25. I had been out of the closet since I was 19. Pretty much as soon as I knew, I told my parents. I came out as bisexual, which is still true for me. I feel like my center of gravity is lesbian. I also love the word queer for the way that it doesn't have to justify anything.

And I also identify as a genderqueer person. I love the embrace of the word queer and I know it doesn't resonate for everyone. I believe in the proliferation of language. The more words the better. So I'm a dyke, I'm a lesbian, I'm also bi. It's all good.

Coming out as bisexual meant that my parents sort of decided, “Oh, she'll come around. It's a phase.” All of that way that bisexuality gets perceived and discounted, but also this narrative of like, "She'll find her straight self." Once I was with a woman and I was like, "This is the love of my life." As soon as I met her, I was like, "This is the one. We're just going to do this thing." She was just amazing.

That was the catalyst, the OK, now this is something you can't look away from because I'm getting married and it's not even legal for us to get married. We're just helping ourselves to this term and declaring, claiming the space of calling ourselves married.

So it was really a process of many years.

JM: Two decades later, has time and becoming a mom yourself changed how you think about being disowned?

CDR: So much. And here's another interesting thing that would happen when I would tell people about the disownment. People would say, "Well, your parents will come around when you have kids because they'll want grandkids and they'll connect." This came from a very well-meaning place. The whole time I thought, well, you don't know my parents. And so, definitely, they did not come around. They actually dug in their heels and tried to turn my siblings against my first child when I was pregnant with the first child. I use that example to say, it's not true that everybody comes around.

The thing that's been really powerful for me is to experience deep in my bones, deep in my blood, the way that it is possible to thrive. We actually don't need the people who have decided to stay mired in their homophobia. Even if they're our immediate relatives, we don't actually need them to thrive. That is the narrative that I see missing a lot of the time. I think often the redemption arc of a queer story of familial homophobia is eventually the family comes around and accepts the queer people. And that's a good narrative. I don't mean to disparage it, but I think the narrative I'm hungry for in the world is the one where we can still absolutely say regardless of that, we don't actually have to wait for home.

If we all wait for all the homophobic people to come around, we're going to give up our whole lives. For me, having kids really rooted me in that.

JM: I think of your writing as being romantic.

CDR: Think so?

JM: I do. Do you not agree with that?

CDR: I don't know. I mean, I write a lot about love and sex and romance. I think that with the word romantic, I have a little bit of a reaction about the way it gets used, not by you in particular, but by the publishing industry to condescend to women writers.

JM: What’s romantic about it to me is the queer joy that’s hidden in your characters. In Cantoras, this deeply oppressive regime, it wasn’t only a story of trauma. These five women were able to find joy and romance. I think that hope is romantic, in a way.

CDR: I might need to do a little work fully embracing the word romantic in relation to my work. And I'm going to sit with it later because there is a way that there's condescension in the publishing industry around women writers using the word romantic. And yet what pulling forward is this other piece about writing about queer joy and writing about sex, yes, absolutely, the prismatic possibilities of sex and queer sex. We don't have enough narratives about queer joy, including queer joy in very oppressive circumstances, which is real and which is so beautiful and part of our infinite resilience and power and beauty as queer people.

Probably every single one of my books has romantic elements. And that's honestly, because I have had an experience in my own life where I'm like, this shit is real. It is possible to connect with a person to the depths of your soul on the margins of society, in a relationship that is reviled by the dominant culture and yet is beautiful, is a palace, is life-affirming, is amazing. I'm still in love with this woman that I married 20 years ago. So I'm not going to shut up about it.

JM: Your new book, The President and the Frog, takes place during the dictatorship in Uruguay and also many years after. It’s loosely based on the former president, José Mujica who was imprisoned for 12 years and spoke to a frog. What sort of internal guidelines did you create to make a book like this work?

CDR: Some of those guidelines come into being before you start writing the novel and some of those come into being as you progress and realize, Am I going to run off the rails? What would help me avoid doing that? But definitely going into this book, I knew from the beginning it was going to be strange. I mean, I am a believer in the weird and the possibilities and power of the weird in narrative. And I think that sometimes our instinct in first drafts can be to flatten the weird, just as our instinct can also be to flatten out the queer or the complex or the nuanced. There's a lot of power and possibility in that which is weird, but maybe has not been said before in that way.

I was interested in that space of José Mujica talking to a frog in that hole when everything seemed lost. What were those conversations? And the question under that question is the really important one, which is what are those conversations that he had with himself that allowed him to not only survive, but come out of that experience with so much hope and vitality, not just for himself, but to make the world a better place or to strive to do so?

JM: I described the book as “weird” as a compliment. I want to read more books that are weird. And you pull it off.

CDR: I personally, as a reader, have read books whose weirdness really opened up possibilities that changed my life. I think the fourth or fifth time that I reread Beloved by Toni Morrison, which is one of the greatest works of US literature or literature in English, in my opinion, I remember reading through and going, "This is weird." And she really trusted the weird and was willing to lean into the weird in order to write that book. And it's a majestic masterpiece. And that is one of my points of inspiration in thinking about weird and literature.

When I first thought of this book, I wrote in my journal back in 2014, if I could ever pull off writing this book, if I ever do embark on it, my dream would be for it to really be a love letter to anyone who's ever felt despair. And through this realm of the parable, be able to write about that journey that we often take from despair to renewal, renewed hope or renewed sense of our own strength or possibility or who we want to be in the world.

Listen to the full podcast interview on Apple Podcasts.

The President and the Frog by Carolina de Robertis is out now.

LGBTQ&A is The Advocate's weekly interview podcast hosted by Jeffrey Masters. Past guests include Pete Buttigieg, Laverne Cox, Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, and Roxane Gay.

Episodes are released every Tuesday