Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy, Yohji Yamamoto’s Great Interpreter

Brand Loyalty is a column that explores one person’s obsession with a brand, silhouette, garment, or color—like Kristen Stewart embracing Outdoor Voices, Kanye West’s love for Vetements., or Isaac Mizrahi’s Belgian Loafer collection.

Perhaps no celebrity became more famous in death than Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy, whose photographs, along with guides on how to get her look, are ubiquitous on Instagram and fan sites. The former Calvin Klein publicist is an icon of ’90s minimalism, a cool and mercurial blonde almost always in black tubes of fabric and well-cut, understated coats. Bessette-Kennedy was only 33 when she died, and only two brief clips of her speaking exist (!), so the world has mostly relied on her understated and even esoteric style choices to construct their sense of her public persona.

But Bessette-Kennedy’s style was a little more complicated than we give her credit for. She was a devotee, for example, of the avant-garde designer Yohji Yamamoto, one of the original group of Japanese designers, along with Issey Miyake and Rei Kawakubo, who came to Paris in the early ’80s and shifted fashion’s focus from the merely glamorous to the richly conceptual. Bessette-Kennedy was such a fan of Yohji-san, as he’s known, that Barneys would call her when new pieces of the designer’s arrived in the store, according to Rosemarie Terenzio, who served as the assistant to Bessette-Kennedy’s husband John F. Kennedy, Jr. at his magazine George. Along with Ann Demuelemeester, Miu Miu, and Prada, Terenzio said, Yohji-san was one of Bessette-Kennedy’s favorite designers—and perhaps that tells us more about her than anything else in her well-studied wardrobe can.

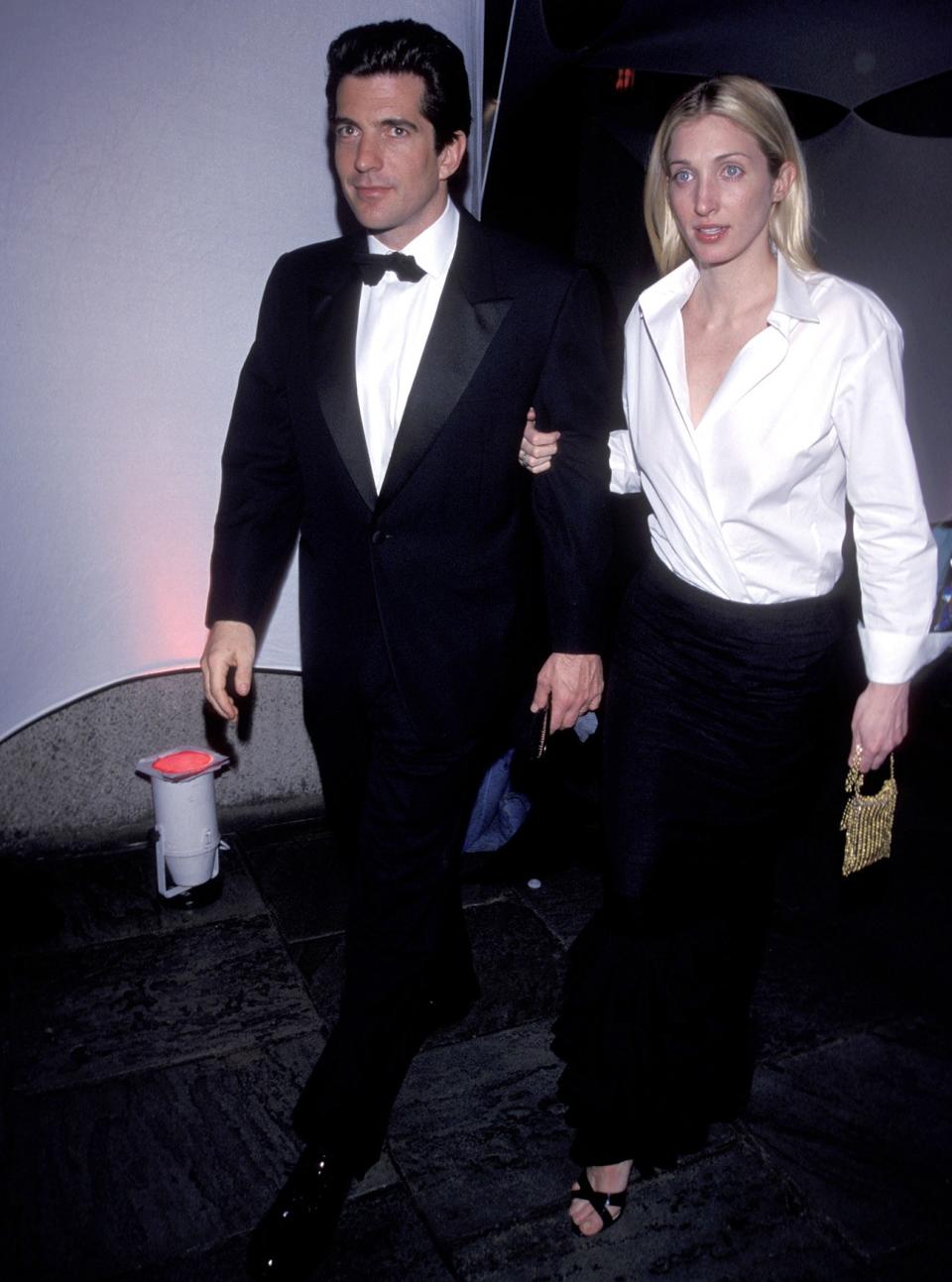

105907362

Ron Galella/Getty ImagesSome of her most celebrated and imitated looks were Yohji Yamamoto. At a benefit for the Whitney in 1999, Bessette-Kennedy wore a white shirt from Yohji Yamamoto Homme, twisted and tucked into a ruffled black skirt from the Spring 1999 women’s collection—a more cerebral take on Sharon Stone’s white men’s Gap button-down and satin skirt at the previous year’s Oscars. Yohji-san loved to mix his men’s and women’s collections; for the Spring 1999 show Bessette-Kennedy’s skirt came from, he had a male model and female model walk the runway together and switch clothing.

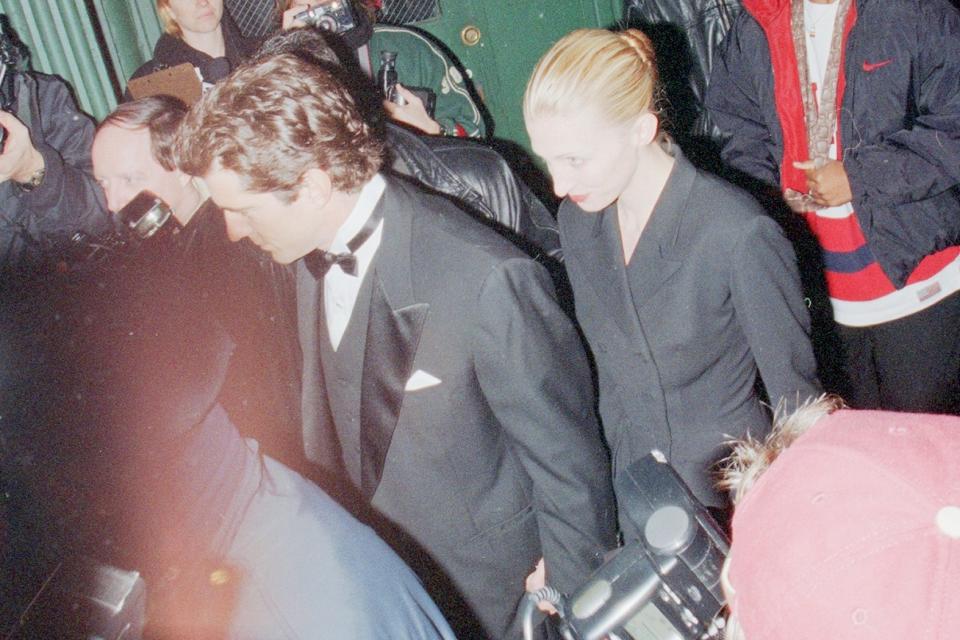

For a party in 1997, Bessette-Kennedy wore a Yohji Yamamoto suit from that season’s collection, a black double-breasted jacket with an hourglass waist, and a matching skirt. (Vogue included a short blurb in the following month’s issue, noting that it “gave her minimalist style and Eastern flair.”) And to a fundraiser in May of 1999, she wore an opera coat with beige ruffles from Spring 1999 (with a Comme des Garcons leather pouch that you can still buy today). All of this is to say: she wore a lot of the pieces as soon as they were available, but she also wore them again and again. This was as the designer intended: “I wanted people to keep on wearing my clothes for at least 10 years or more, so I requested the fabric maker to make a very strong, tough finish,” Yohji-san said in a 2011 interview with The Talks.

110448806

Time & Life Pictures/Getty ImagesYohji-san offers interviews only in person during fashion week, but a spokesperson confirmed that Bessette-Kennedy had a “very strong relationship with the house from 1996 until 1999.” The two never met—although, the spokesperson noted, the designer sent a memorial message to WWD when Bessette-Kennedy passed away. (Yamamoto no longer has a copy since he faxed the only one to the paper.)

As her Yohji Yamamoto looks show, what makes Bessette-Kennedy’s style so memorable isn’t merely her minimalist taste, but her grasp of the very idea: she really loved avant-garde fashion. Her celebrity peers, like Princess Diana, liked the flash of Versace and the snobbier minimalism of Armani. And other fashion icons of American politics, like her mother-in-law, Jackie Kennedy, or Nancy Reagan, preferred French couturiers and their American counterparts, who stood for a kind of whole-milk glamour—Oscar de La Renta, James Galanos, Bill Blass, Ralph Lauren. Bessette-Kennedy seemed to feel better in something weirder.

So what drew Bessette-Kennedy to Yohji-san’s designs? In a 2016 story on the “one-woman fashion cult,” Town & Country suggested that her wardrobe reflected the tumult and insecurity that allegedly follow the Kennedys’ wedding: “Prior to their marriage, Carolyn was often photographed in the slinkiest of outfits…. Afterwards the necklines went up, up, up. When she did appear at official events in public, it was almost exclusively in uncompromising designs of Japanese avant-garde Yohji Yamamoto, her famous luscious hair severely pulled back, almost school-marmish.”

In other words: the fittingly sad wardrobe for America’s saddest fairytale. But that timeline doesn’t quite line up—nor is it consistent with Yohji-san’s work. First, Bessette-Kennedy’s concerns were more practical, according to Terenzio: “When John started George, Carolyn had to make sure not to wear one designer over another because they advertise in the magazine. So she wore a ton of Yohji because they didn’t advertise at all.”

And there’s something beyond that business-savvy, too—the intellectual intention that Yohji-san stands for. As Yohji-san said in a 2011 interview, “My starting point was about wanting to protect a human’s body.” He continued, “I wanted to protect the clothes themselves from fashion, and at the same time protect the woman’s body from something—maybe from men’s eyes or a cold wind.” Bessette-Kennedy couldn’t hide from the public, but she could find clothing that made her feel in control.

Originally Appeared on GQ