Carpenters Creek Connected shares how Pensacolians lives intertwined with imperiled creek

Carpenter Creek has meant many things to Pensacolians who used to play, swim or were even baptized in its water, but it has always been a nexus of community gathering and connection.

New Hope Missionary Baptist Church used to baptize its members in the cold, clear waters of the creek in a place called the Rock Pile, a swimming hole for the Black community. Church members Aserdean Soles and Novella Kelly vividly remember the creek as a place where peopled transitioned into a new chapter of their life.

Their stories have been recorded and included in a University of West Florida class project called Carpenter’s Creek Connected, which compiles 20 oral history testimonies that will be deposited in the UWF Historic Trust archives in the spring.

Carpenter Creek restoration15 projects unveiled to restore Carpenter Creek call for increasing public access to creek

Landslide 2021 reportAdvocates hope report naming Carpenter Creek a 'threatened cultural landscape' sparks action

Taylor Brown, a historic archaeology graduate student, felt it was amazing to capture these “lost memories” from the creek that are central to people who lived along the creek and that helped shape who they are today.

“We talked a lot in the oral history class about how the typical history you learn is kind of the bird's eye view, and so you read about Pensacola and you learn about the city of Five Flags and all these big kinds of things that happen,” Brown said. “But oral history really allows you to see history through one person's perspective, and so hopefully 30 years from now when someone goes and listens to Aserdean Soles' interview, they're gonna get to see Pensacola through her eyes and how she grew up in the town and understood it, and how when she was growing up affected how she grew up.”

The Oral and Community History class is taught by UWF history professor Jamin Wells and focuses on identifying community partners who are working on projects related to U.S. history, learning from them and supporting them.

Wells had little knowledge about Carpenter Creek until he read the "Landslide 2021: Race and Space" report last year. In the document, Washington, D.C.-based organization The Cultural Landscape Foundation identified the waterway as one of 13 culturally significant landscapes associated with African Americans, Hispanic Americans and Native people across the county that are threatened to be erased from the landscape.

Wells partnered with Angela Kyle — a direct descendant of Jannie Hudgins, whose family owned 10 acres along the creek known as "Aunt Jenny's Swimming Hole" — and other community members who have been advocates in restoring the waterway.

“I like to think where history and these oral histories can contribute to that conversation is understanding how the space has been used and how the value of the creek has sort of changed over time and seeing just how robust that has been,” Wells said. “I think we can help potentially imagine the future by understanding where we came from and also understanding what kind of levers were pulled to create ... the many environmental challenges it faces today.”

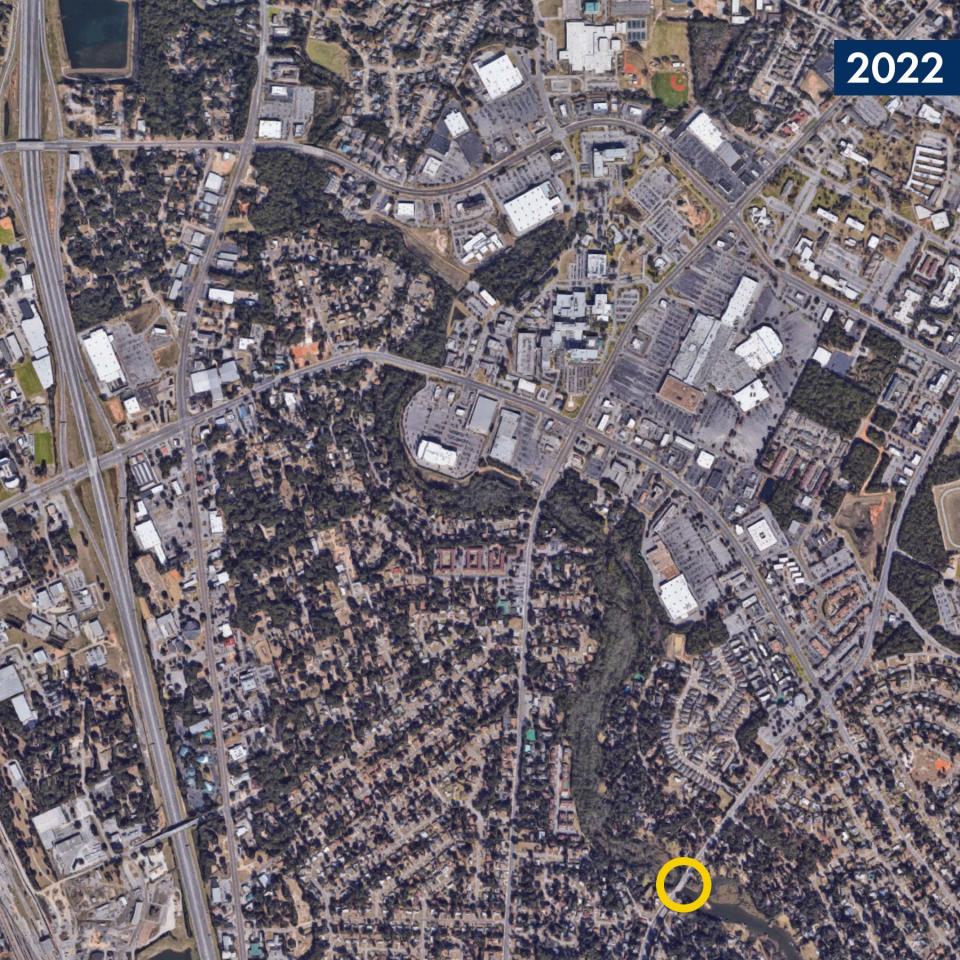

Carpenter Creek (also called Carpenters Creek by many Pensacola residents) begins at a springhead near Olive Road, winds under Interstates 10 and 110, and Davis Highway, under Ninth Avenue past the mall and multiple shopping centers, then opens up past 12th Avenue into Bayou Texar, according to the University of Florida's Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

The water way has been developed over and around for decades, and has long been plagued by pollution — from contaminants that wash in from roadways and businesses, to shopping carts and household appliances that are abandoned on its banks.

When searching for information about the creek, students went through any documentation they could find, from historic maps to old newspaper clippings. They realized how there was almost a hole in understanding the creek but it didn’t deter them from accumulating 20 hours of audio from 22 narrators and capturing a variety of views to try and understand what this creek meant to people.

The class when as far back as the early 1800s and discovered the creek was used as a municipal dump, as the site of a sawmill in the early 19th century, that there was a convict labor camp off the creek in the early 20th century, that it was used for fishing and moonshining, and later as a sewer when the city expanded.

More: Carpenter's CreekCollapsing parking lot a symptom of larger problems in Carpenter Creek, advocates say

It became the home of small communities of Black and white families around the turn of the 20th century. The mid-to-late 20th century saw commercial and residential development and increasing pollution problems.

After many years of advocacy from citizens and elected officials, state and local governments are poised to invest $8.1 million toward projects that will improve the health of Carpenter Creek and Bayou Texar.

Graduate student Chrissy Perl was among many who drove over the creek every day and knew nothing about it. But Perl has learned the area is rich with history and meaningful stories.

“I think it's important to know the past and what were the situations or the steps that brought us a creek almost dying out, almost forgotten,” Perl said. “And then the other part is remembering the communities that flourished along the creek. I think we need oral histories (which are) important to keep those memories alive not only for the elderly community members, but also for the new generations coming in.”

Angela Kyle views the UWF class project as important because it helps shed a light on the "Landslide 2021: Race and Space" report and how there's a living, social, cultural and human side to the story that is as important as the environmental side of it.

The class project can help push the planning process of the restoration into a design phase and give the engineers, landscapers, and consulting team a chance to hear these human stories and bring the restoration project to life with nuance and detail, she said.

Carpenter Creek was a symbol of connectivity, as the people who grew up in the area usually had stories of walking from church or their job — like Kyle’s great grandmother and great grandfather had to do.

“The idea of this natural feature of the landscape that plays this role and then you layer on top of that, the social connection, this kind of nexus of the Black community, the white community, the sacred, the secular, the commercial … you kind of layer all of that on together and it's incredibly powerful,” Kyle said. “And I think that's really the spirit of why the restoration really matters.”

To see more of the project go to its Instagram page Carpenters Creek Connected.

This article originally appeared on Pensacola News Journal: Carpenters Creek Connected is oral history of vital Pensacola creek