‘Casablanca,’ a night in Fayetteville and a film that boosted WWII America

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Saturday, Feb. 6, 1943 — 80 years ago — had been a balmy winter’s day in Fayetteville, North Carolina. The daytime temperature reached 70°, which appeared comforting to the crowds that gathered downtown during the midst of the war.

Fayetteville had grown considerably since 1939, when President Franklin Roosevelt announced plans to enlarge Fort Bragg and other Army installations.

More:Opinion: Christmas during wartime, a look back at the holidays during WWII

The Fayetteville Observer, like many newspapers published near military cities, provided its readership a combination of national news, regional concerns and local news reports focused on new buildings under construction, local entertainment, the comings and goings of soldiers, and the prosperity that nearby Fort Bragg brought to the local economy.

The headline that Saturday read in all caps, “RUSSIANS APPROACHING RESTOV.” The Observer also noted that the Sunday afternoon concert at the Winslow U.S.O. Club was postponed. In the comics, Dagwood complained about the weather and asks, “Blondie, where’s my other rubber? I can only find one.” “That’s all you have for now Dear,” she replies, “I gave the other one to the government scrap rubber drive.”

More:Memorial Day: The sacrifice of the Sullivan brothers

It had been a busy Saturday. The downtown area was so crowded that people standing on the sidewalks spilled out into the streets, traffic was at a standstill and stores, in spite of rationing, were jammed with shoppers.

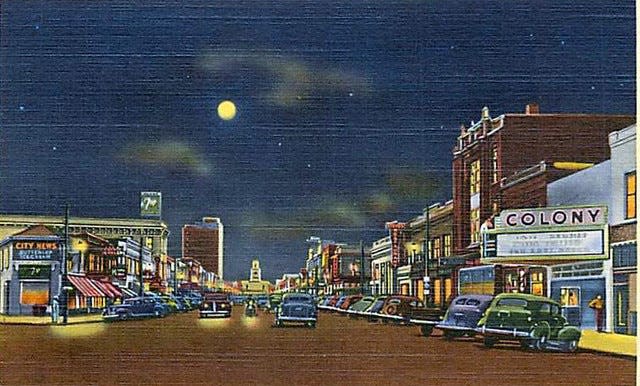

President Roosevelt called the movie theater a “necessary and beneficial part of the war effort,” and the Colony Theater (located at 329 Hay Street) contributed its part. That night outside the theater people queued up. The film that they were about to see had Nazis, refugees, scoundrels and themes of patriotism, unrequited love, redemption and of course plenty of booze.

More:5 movies filmed in the Fayetteville area

The movie opens in Morocco in December 1941. A cynical American expatriate meets a former lover, with unforeseen complications. This is Casablanca. “Here the fortunate ones through money or influence or luck might obtain exit visas,” says the narrator. “But the others wait in Casablanca, and wait and wait and wait.”

Warner Bros. bought the rights to Murray Burnett and Joan Allison's play “Everybody Comes to Rick's,” shortly after America’s entry into the world war, for $20,000, then the highest price ever paid for an unproduced play. Hal B. Wallis, the movies producer, changed the title to “Casablanca.”

Several writers contributed to the script, resulting sometimes in three different versions of a scene for Wallis and director Michael Curtiz to choose from. When a complaint was raised that some of the changes were illogical, Curtiz replied, “I make it go so fast that no one notices.” In the end, writers Julius, and his twin brother Philip along, with Howard Koch would share the Academy Award.

A phenomenally talented group

When filming for “Casablanca” kicked off on May 25, 1942, Humphrey Bogart, cast as cynical romantic Rick Blaine, was one of Hollywood go-to heavies. Square-jawed and narrow chested, Bogart had a five o'clock shadow and a mood to match. He was rarely the guy to get the girl in the film and was filled with anxiety that he would not be able to pull off Casablanca’s “love stuff” as he called it.

Ingrid Bergman, as Bogart love interest Ilsa Lund, was equally conflicted. The statuesque Swede wanted to make her mark as a serious actress, not as another Hollywood ingenue. She had hoped to be cast in a different film altogether and dismissed “Casablanca” as fluff. Sixteen years Bogart’s junior, Bergman would later lament that she had kissed her costar, but never got to know him.

Yet, once director Michael Curtiz trained his lens on the pair, they're smoldering on-screen magic was unmistakable. Bergman, shot through gauze filters with her eyes sparkling from catchlights, glows under Bogart’s glaze. Bogart's face is a map of hardness; the café owning cynic who early in the film declares, “I stick my neck out for nobody,” becomes transformed into a patriot who sacrifices his love to help protect Europe from the Nazis.

It was Bogart who coined the phrase, “Here's looking at you kid,” adapting the original, “Here's good luck to you.” Bogie was also responsible for changing, “Of all the cafés in all the cities in all the world, she walks into my café” to the somewhat snappier, “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.”

While Bogart and Bergman were front and center, they were surrounded by a phenomenally talented group of unusual suspects who helped make the movie a success.

Dooley Wilson, cast as the piano player, plays Rick’s loyal friend Sam, the one who looks out for his best interests. Producer Wallis considered changing the character's gender, with Ella Fitzgerald and Lena Horne among those considered for the part. Ironically, Wilson was a drummer, not a pianist, miming to a pianist who sat off-camera and tinkled the ivories yet sang all the songs in the film.

It should come as no surprise that Claude Rains was the first choice to play the corrupt, lecherous, Vichy Captain Louis Renault who is, “shocked — shocked — to find that gambling is going on” at Rick’s even as he receives his winnings from the croupier. Rains, who was nearly blinded in one eye during World War I, left the British Army as a Captain and moved to the New York stage. He was also a former acting teacher, with legendary performers John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier among his students.

British actor, Sydney Greenstreet, plays the polite and insidious Signor Ferrari, boss of Casablanca’s underground traffic in visas. On screen for less than 5 minutes, the nearly 300-pound Greenstreet is effete and insinuating from his first big scene where he hovers over Sam, seeking to lure him away from Rick.

Ferrari: “What do you want for Sam?” Rick: “I don't buy or sell human beings.” Ferrari: “Too bad. That's Casablanca’s leading commodity.”

Some actors had escaped Nazism

Many of the actors were themselves, first-hand victims of the Nazi regime. Peter Lorre who plays Ugarte — whose early arrest in the café sets the plot in motion by killing two German couriers to obtain valuable letters of transit — had himself escaped Hitler in 1933.

Originally, the aristocratic Austrian Paul Henreid refused the part of Victor Lazlo, balking at playing the second romantic lead to Bogart’s Rick Blaine. But after the United States entered the war, the country began deporting many “enemy aliens,” regardless of their politics; Henreid, who had left Austria for his vociferous anti-Nazi stand, accepted the film contract to save his life.

S. Z. Sakall, who played Carl the waiter, was a Jewish-Hungarian fled Germany in 1939; he lost his three sisters in a concentration camp. Helmut Dantine, who played the Bulgarian roulette player, spent time in a concentration camp and left Europe after being freed.

Curt Bois, who played the pickpocket, was a German-Jewish actor and refugee. Conrad Veidt, who played Major Heinrich Strasser, was a German film star and refugee. Despite being Jewish, he often insisted on being cast as a Nazi officer to bring attention to their villainous deeds.

The dewy-eyed Madeleine Lebeau was just 19 when she appeared as Rick’s soon-to-be-discarded girlfriend. Like the fictitious protagonists Rick and Sam, she had her own real escape: leaving Paris just hours ahead of the conquering Germans. Making her way to Lisbon, she used a forged Chilean visa, and booked passage to the States where she secured papers that allowed her to legally enter California.

Lastly, director Michael Curtiz, best known for adventurous swashbucklers such as “Captain Blood and the Adventures of Robin Hood,” was a Hungarian-Jewish immigrant who had arrived in America in 1926, but some members of his family were refugees from Nazi Europe. “Casablanca” would win him the Academy Award for Best Director. In all, the cast included 34 nationalities.

The plot involves letters of transit that allows two people to leave Casablanca for Portugal and ultimately freedom. The movie opens in Rick's Café Americain, where refugees are pawning rings, customers lighting cigarettes and Nazis drinking Veuve Clicquot ‘26.

Rick obtained the letters from the wheedling little black-marketeer Ugarte. Ricks retreated to a world of utter isolationism — no family, no love, no past or future, just him, Sam and his bar. “What is your nationality?” asks the Nazis’ Major Strasser. “I’m a drunkard,” says Rick. “And that makes Rick a citizen of the world,” says Claude Rains’ Captain Renault.

Into this setting turns up Ilsa Lund with her husband Victor Lazlo, whom she thought dead, when she shared a pre-war romance with Rick in Paris. Lazlo is leader of an underground anti-fascist movement in Europe, and it is vital that he escapes to America. The sudden reappearance of Ilsa, a freedom fighter in a satin gown and diamond ear clips, reopens old wounds, and breaks Rick’s carefully cultivated veneer of neutrality and indifference.

It’s this world that Ilsa destroys when she walks into the cafe on the arm of Laszlo, the handsome, noble resistance hero, the suave, principled hope of millions enslaved by the Third Reich’s tyranny, bringing back the pain of lost love. Until her appearance, the movie is a timebound melodrama. But of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into Rick's, ultimately redeeming not just him, but giving hope to a conquered Europe.

When Rick recalls that last dreary rainy day in Paris with Ilsa, he says: “The Germans wore grey, you wore blue,” to which she replies “I put that dress away. When the Germans march out, I'll wear it again.”

And we believe her! Who cannot get goose bumps watching him pound back bourbon in the empty cafe, saying, “She's coming back. I know she's coming back.” And then not only does she appear, but as a miraculous redeeming luminous angel standing in the doorway.

A timeless song — almost cut from script

Before her appearance, Wilson, who sings the hit song, “As Time Goes By,” tries to save Rick: “We'll take the car and drive all night. We'll get drunk. We'll go fishing and stay away until she's gone.”

“As Time Goes By,” composed 11 years earlier, was specified in the play. Composer Herman Hupfield had been a college roommate of playwright Burnett.

However, composer Max Steiner hated the song, insisting that the six-note ditty was too simple for a love theme, and the song was almost cut from the film at the last minute. Only the fact that Bergman had already had her hair cut for her role in “For Whom the Bell Tolls” prevented Wallis from reshooting the scene in which she asks Sam: “Play it, Sam. Play ‘As Time Goes By.’”

When Rick finally hears Ilsa’s story, he realizes she has always loved him. Rick wants to use the transit letters to escape with Ilsa, but then, in a sequence that combines suspense, romance and comedy, he contrives a situation in which Ilsa and Laszlo escape together.

Why? Like Romeo and Juliet, Tristan and Isolde, Rhett and Scarlett, Rick and Ilsa can never be together — can we really picture them living in Southern Pines, with kids, a golden retriever, and a manicured lawn?

No! Love is sacrificed for a higher principle. As in Rick's famous line: “Ilsa, I'm no good at being noble, but it doesn't take much to see that the problems of three little people don't amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world. Someday you'll understand that.”

A morale boost in war time

“Casablanca’s” greatest contribution to the war effort was morale. The movie was a patriotic rallying cry that affirmed a sense of national purpose. The film emphasized group effort and the value of individual sacrifices for a larger cause. It portrayed World War II as a peoples’ war, typically featuring a diverse group of people and ethnic backgrounds who are thrown together, tested, and molded into a dedicated fighting fascism.

That Saturday in February, reported an advertisement in the Observer: “Out of the headlines and into the Colony theatre! That’s the story behind the up-to-the-minute thriller, ‘Casablanca,’ as exciting and timely as you’ll ever see.”

Indeed, “Casablanca” met its mark, taking Fayetteville on a spiritual quest to the Moroccan desert and giving it irony and a center table in a nightclub. It has more redemptions than a Sunday morning radio evangelist. Spurned Yvonne may date a Nazi Officer, but when the band strikes up the “Marseillaise,” she's singing. Corrupt Captain Renault redeems himself with a lie.

The unrequited love between Rick and Ilsa is worthy of a Shakespeare sonnet: “We'll always have Paris.”

Dr. Cristóbal S. Berry-Cabán a native of Puerto Rico, is a senior research scientist with Womack Army Medical Center.

This article originally appeared on The Fayetteville Observer: ‘Casablanca,’ a night in Fayetteville and a film that boosted WWII America