The Case for a Notre-Dame That Could Be

“A restoration may be more disastrous for a monument than the ravages of centuries.” So the novelist and archaeological preservationist Prosper Mérimée cautioned Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, a brilliant young architect, back in 1843, when he and Jean-Baptiste Lassus were tapped to reverse the injuries that the French Revolution had inflicted on Notre-Dame de Paris, the 856-year-old centerpiece of Île de la Cité that so spectacularly burned on Monday, filling the cloudy skies with soot and ash and transforming a beloved building into a hellish orange lantern for some 12 soul-crushing hours.

That the two architects manipulated the physical record of Notre-Dame in favor of something more picturesquely yet inaccurately “medieval” is beyond question. Among other things, the more-than-two-decade recasting of Notre-Dame saw original statues removed in favor of modern replacements; a flamboyant new pulpit carved to Viollet-le-Duc’s design; the south façade’s rose window tinkered with; a spiky wood-and-lead spire, known as la flèche, erected, which would become the building’s defining feature despite its playing fast and loose with historical precedent. “Viollet-le-Duc should have worked for Disney,” Paris-born photographer Daniel Aubry wryly told me last night at a jam-packed book signing for AD100 decorator Bunny Williams, where Notre-Dame was the topic of the evening. As for the architect’s flamboyant geometric murals, critic Charles Hiatt dismissed them as “dead and mechanical” in his 1902 book about the cathedral. Still, Hiatt continued, “Though I regret so-called ‘restoration’ on principle, I cannot help feeling that the work executed by M. Viollet-le-Duc and M. Lassus is far less objectionable than it might have been.”

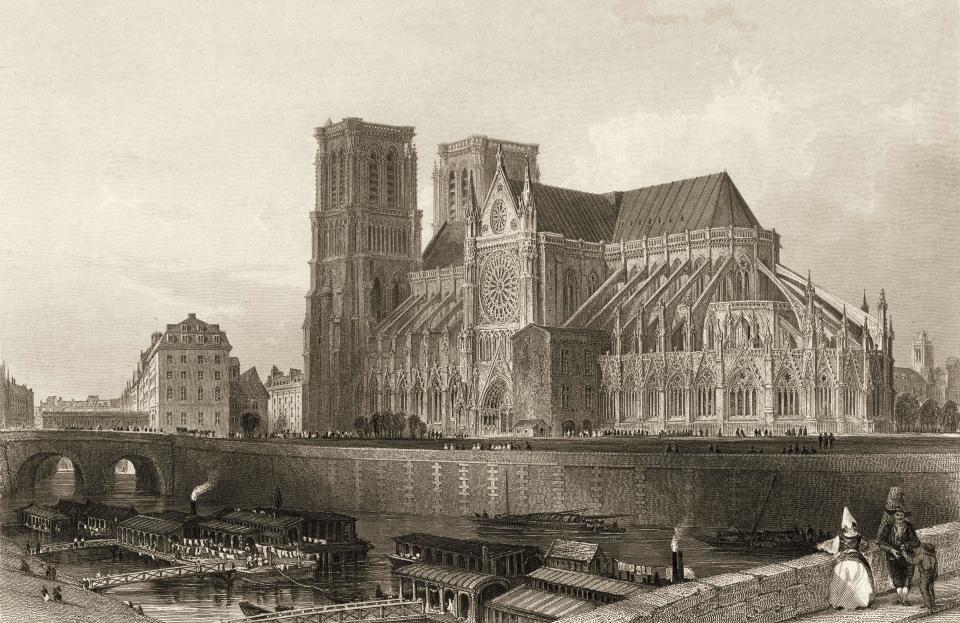

Notre-Dame Cathedral

Which leaves us with a couple of questions: How will Notre-Dame be restored, and precisely which Notre-Dame—a building that has been altered, adjusted, modified, and even mutilated over the centuries and is arguably a 19th-century construct—should be revived?

“We will rebuild Notre-Dame even more beautifully, and I want it to be completed in five years," President Emmanuel Macron said, though experts note that his optimistic timeline falls short by at least a decade. A billion-plus dollars had already been pledged at press time toward the charismatic French premier’s noble goal by LVMH, L’Oréal, Kering, the Fondation Bettencourt Schueller, and other French and international corporate entities and private citizens. (The Pinault family behind Kering also has renounced any tax benefits that result from its donation.) On Tuesday, Château de Versailles and Château Mouton Rothschild, the illustrious Bordeaux winery, announced that the proceeds from the second in a series of three Sotheby’s wine auctions intended to benefit restorations at the former royal palace will be instead given to Notre-Dame; the auction in question occurred today in London, and it raised $983,148 for the cause.

Given the justifiably anguished comments on social media about the Paris blaze, one supposes that most mourners are jonesing for a simulacrum Notre-Dame, a sort of sanctified hologram. But is that really the best solution? Should the powers that be corral the talents of artisans, craftspeople, architects, designers, historians, and the like in pursuit of a photocopy, even if there is a digital 3D scan of every single detail to guide them? I humbly (and perhaps provocatively) suggest taking this Holy Week horror and using it to contemplate not only the Notre-Dame that was—stern on the outside yet transporting on the inside and riddled with fanciful, and in their time, modern anomalies—but also the Notre-Dame that could be.

The Stryge looks at Paris

Notre-Dame should remain and continue to be what it always has been: an ancient house of worship that appears unchanged to casual eyes but which actually knits together the past and the present, offering a panoply of French history and culture across more than eight centuries. Firewalls and a sprinkler system, too, both of which were shortsightedly not built into the cathedral.

The precedents for sensitive inventions are many. When St. George’s Hall at Windsor Castle was consumed by fire in 1992, restoration architect Giles Downes employed an English Gothic language that echoed what history had wrought—the hall’s long-lost 14th-century appearance inspired him—but in a cleaner, more contemporary fashion while nonetheless utilizing sustainable materials and depending on traditional craftsmanship. Then there’s the example of Notre-Dame de Reims, Notre-Dame de Paris’s near twin, where 31 French kings were coronated. Gutted by German artillery in 1914, it was restored by architect Henri Deneux in the Gothic spirit, though it incorporated current amendments. The framework of the new roof was made of fire-resistant reinforced cement; eventually, the cathedral also received a set of abstract stained-glass windows by German artist Imi Knoebel in 2015. These interventions keep the structure alive and of our time, just as Notre-Dame de Paris incorporated some modern stained glass from the 1940s.

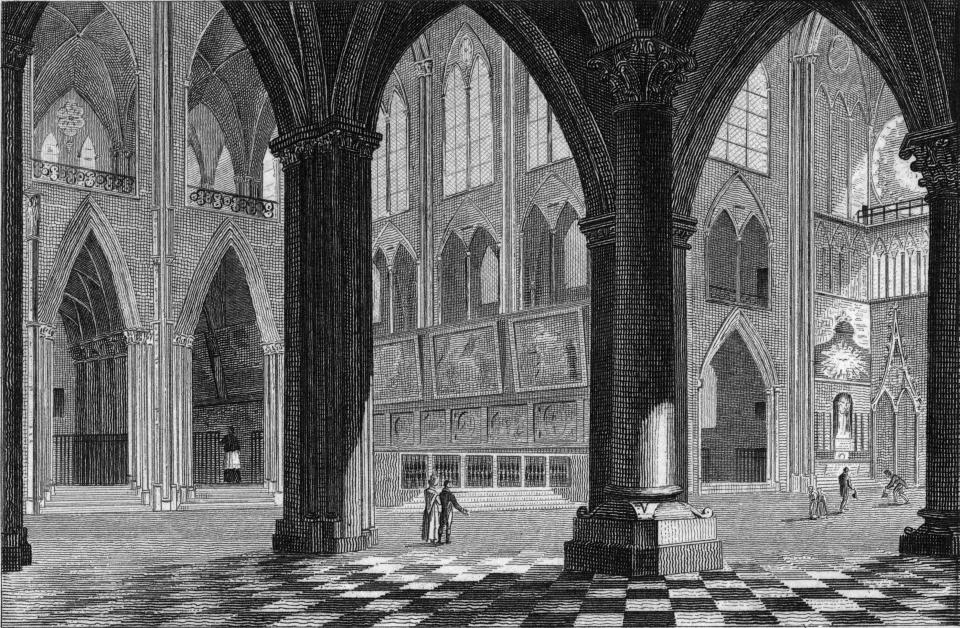

Notre Dame

I was struck by comments made this week by Becky Clark, the Church of England’s director of cathedrals and church buildings. “No matter the destruction, the spirit of what it means to be a cathedral can and does survive such catastrophes,” she said, referencing historic English churches that have been gravely damaged and ultimately reborn, “sometimes taking on new forms, to stand as reminders of eternity and resurrection which are the foundation of the Christian faith.” Mirabile dictu, Notre-Dame’s great 13th-century-meets-Viollet-le-Duc rose window, has survived. So have the stone walls, vaulting, twin towers, 1860s organ (Viollet-le-Duc cannibalized the 18th-century one for parts), ten bells (some new, some old), and more, including the high altar and its great golden cross, shining above piles of charred rubble. I do not mean to suggest reversing Viollet-le-Duc’s Gothic pastichery, which some people have been surprised to learn isn't medieval at all (cue numerous gargoyles). Rather, I would encourage the restoration committees to hire young architects and designers and encourage them to be inspired by Viollet-le-Duc's legacy, replacing whatever of his work has gone missing in action—like the destroyed spire—with 21st-century Gothic statements in the same way that Viollet-le-Duc created his own Gothic vocabulary in the mid 19th century.

The Notre-Dame tragedy affords an opportunity to prove that the architectural languages of the past are still fluently and inventively spoken. All one has to do is look at the buildings of AD100 architects Robert A.M. Stern and Peter Pennoyer to understand that 21st-century classicism is not an oxymoron. Imagine what insights AD100 architect John Pawson could bring to Notre-Dame’s table—a radical notion, perhaps, but given the British genius’s experience with reanimating venerable holy sites, such as Augsburg’s St. Moritz Church, a fresh yet reverent eye might be just the thing to galvanize the French cathedral’s future restoration team, even if they disagree with Pawson’s rigorously luminous philosophy of spatial purity. Why not ask Rick Owens, the idiosyncratic Paris-based fashion and furniture designer, to develop moody, obsidian-dark stone or scagliola pews that would supersede the banal rush-seated wood seating that seems to have escaped Monday’s bonfire? If the cathedral’s chandeliers have been grievously damaged, I would nominate Hervé van der Straeten, an innovative Paris designer whose work is already in the French Ministry of Culture’s Mobilier National, to create new ones. Surely there’s a role, too, for AD100 architect Isabelle Stanislas, who recently put her modern stamp on some state rooms at Élysée Palace.

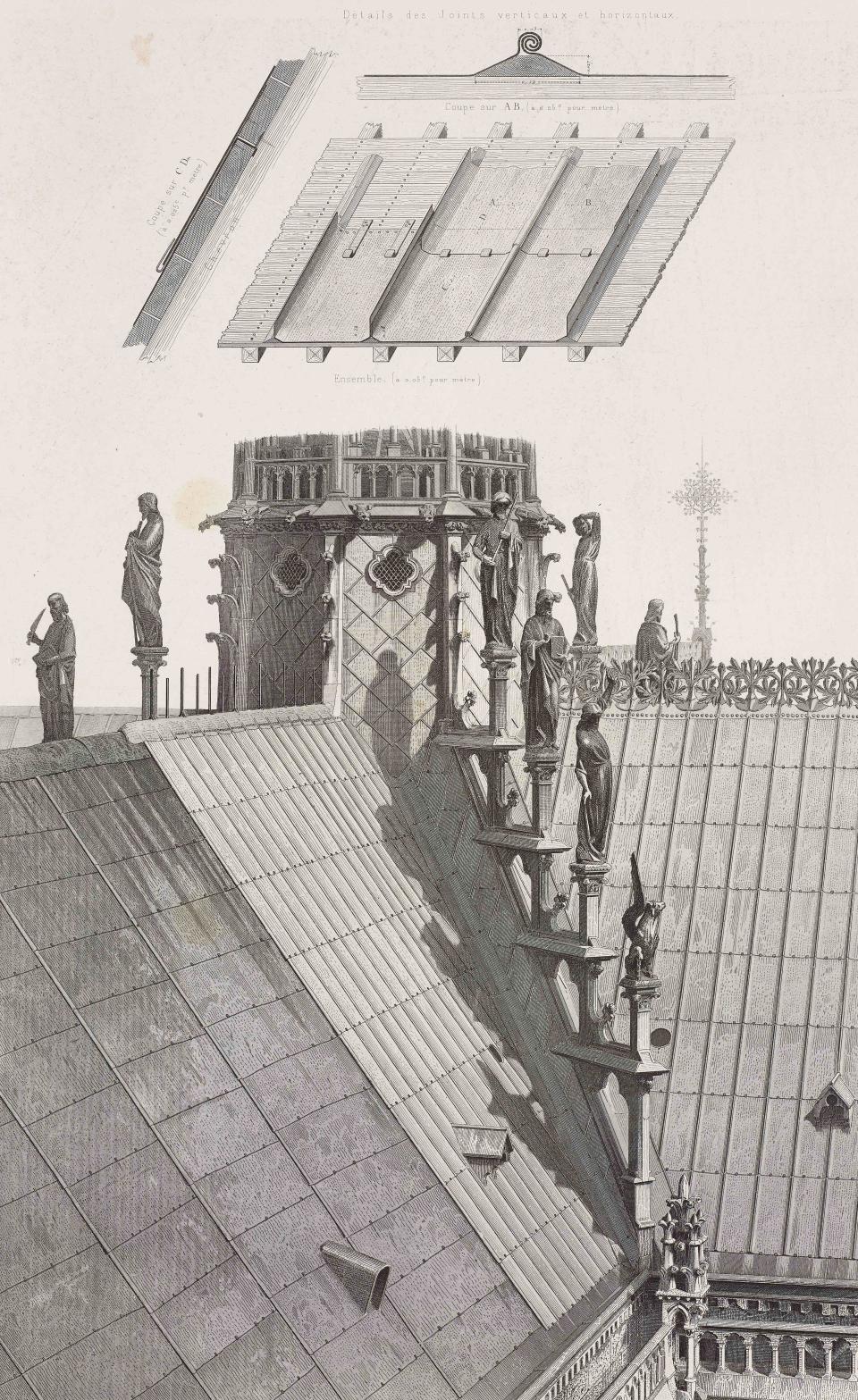

Architectural detail on roof of Notre-Dame cathedral, Paris, France, engraving by Gibert from Revue generale de larchitecture et des travaux publics, by Cesar Daly, 1866, Paris

Conjuring up a copy of Notre-Dame or reproducing its missing or damaged elements is a fool’s errand, even though Viollet-le-Duc’s sponsor, Mérimée, championed facsimiles in his role as France’s inspector general of historical monuments. “Reproduce with prudence the parts destroyed, where there exist certain traces,” he decreed. “Don’t give yourself to inventions.” To that I say—as surely Viollet-le-Duc silently did—why ever not? Even the most exacting reproduction is ultimately the triumph of cloning over creativity. Macron’s determination to rebuild Notre-Dame “even more beautifully” might hold the key to the cathedral’s escape from the ashes and to provide the world with renewed hope. An international competition to design a new spire has already been announced, and today French prime minister Édouard Philippe has called for “a spire adapted to techniques and challenges of our times.” Looks like we’re on the same page—it’s time for a new Viollet-le-Duc.