Cash transfers would help more families than meagre food parcels, campaigners say

Crisis charities have reiterated that cash transfers, rather than food boxes, are the best way to help hungry families, amid a row over "woefully inadequate" free-school meal bundles being sent to families in lockdown this week.

Downing Street launched an urgent inquiry into the standard of food deliveries offered to some schoolchildren in England after a number of photos depicting the parcels surfaced on social media on Tuesday.

Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer tweeted that the food appeared to be "woefully inadequate" and said it needed "sorting immediately", while footballer turned campaigner Marcus Rashford said “children deserve better”.

But anti-poverty organisations, including Save the Children and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, are calling on the Government to reconsider the policy all together. They point to a large body of international evidence that shows money, not food, is the most efficient and effective way to distribute emergency aid.

Speaking to the Telegraph, Save the Children’s executive director Kirsty McNeill said empowering parents through grants often leads to better health outcomes for malnourished children.

“In several countries, including Nigeria Cambodia, Myanmar, we found that regular transfers to the primary caregivers – that's most often the mums – alongside some information about good nutrition, can lead to reductions in chronic malnutrition, between eight to 18 per cent,” she said.

“That’s absolutely transformative.”

Then imagine we expect the children to engage in learning from home. Not to mention the parents who, at times, have to teach them who probably haven’t eaten at all so their children can...

We MUST do better. This is 2021 https://t.co/mEZ6rCA1LE— Marcus Rashford MBE (@MarcusRashford) January 11, 2021

Schools have the freedom to decide how they provide free school lunches to children learning from home. This may include lunch parcels, local vouchers or the Department for Education’s national voucher scheme.

Following Tuesday's backlash from campaigners the Government has today promise to reinstate the National Voucher scheme, offering backdated refunds to schools who had already invested in food parcel schemes.

In the past, there have been fears raised that cash transfers will lead to increased spending on alcohol, tobacco or other “luxury” items. But Ms McNeill says there is little evidence to back this up, citing a study by the World Bank which looked at 44 estimates across 19 different studies on the subject.

Save the Children has been caring for the needs of children in a number of humanitarian disasters and conflict zones for more than 100 years, but the charity, which was founded in the UK, also has a long history of supporting poor children in Britain.

At the start of the coronavirus crisis the charity set up an Emergency Grant for families living on the breadline.

The grants provide low income families with basic household items and practical resources to support them throughout the pandemic. More than 10,000 children have already used the programme.

From Save the Children’s experience, cash transfers are one of the more cost effective ways of delivering aid: they support the local economy and, unlike food parcels, you don’t need to build an entire new production line from scratch, Ms McNeill said.

“The only environment in which we haven't got a very strong preference for cash programming is where the food supply has been so disrupted by a war,” she said.

“There are a small number of places where you just can't get access to nutritious food reliably other than bringing it in. But that's clearly not the situation we're in in the UK.”

Even food vouchers with set conditions have a better long-term impact on people’s mental health and economic prosperity, says Ms McNeill, as prepackaged food boxes can often leave parents feeling disenfranchised and frustrated with the provisions that have not been tailored to the needs of their families.

“Anywhere in the world if somebody's getting assistance, it is because and only because they have less money... so why would we design something that feels like a punishment or a humiliation?” she said.

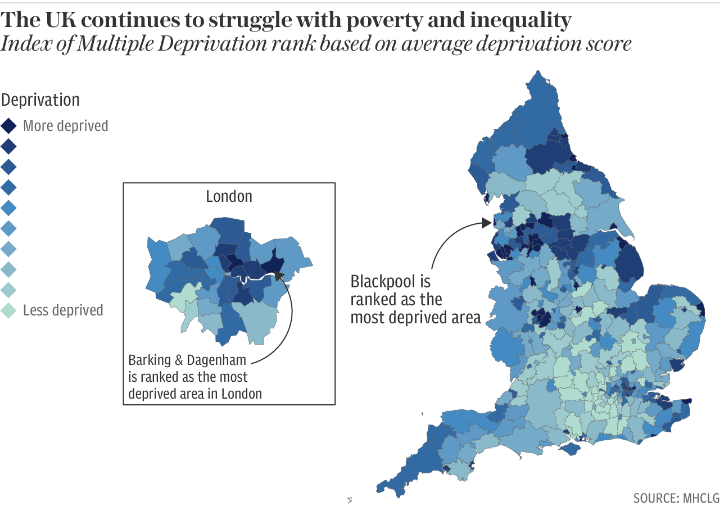

One in four children are living in poverty across the UK, and in some parts of the country, cash transfers are already being used, added Helen Barnard, director of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

“Most of Wales and parts of Scotland turned pretty quickly to cash grants, instead of through parcels or vouchers, because they immediately recognise this is the most efficient way we can make use of our budgets,” Ms Barnard said.

“It seems very odd for England to create a whole new system, which is going to be administratively heavy, when we could just do a boost to child tax credits or use local welfare assistance. The Government seems to be bending over backwards not to deliver the most efficient solution.”

A new report published by the foundation today on what families are facing calls on the government to permanently commit to a temporary £20 per week rise in universal credit benefit payments – which is due to be cut from the end of March.

All the evidence supports putting money straight in the pockets of parents, she said.

“There are immense amounts of incredibly robust research showing that when you boost incomes, people on the lowest incomes disproportionately spend that money on essentials, which is completely obvious if you've ever met a family,” she said.

“We all want to live in a society where everybody is able to afford the essentials to stay healthy and to have their dignity.”

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security