Castro confiscated his apartments in Cuba. American diplomats and now tourists stay in them

Javier García-Bengochea, a successful neurosurgeon in Jacksonville, was just a baby when he left Cuba with his family, after Fidel Castro confiscated their businesses and properties in 1960 as part of a broad expropriation effort that triggered what was to become a six-decade U.S. embargo.

Several years later, two high-end apartment buildings in Havana’s exclusive Miramar and Alturas de Miramar neighborhoods, seized from his family, ended up as a profitable Airbnb rental and residence for American diplomats in Havana. García-Bengochea says both the American company and the U.S. State Department owe him money.

“At least State claims to serve our diplomatic corps. Airbnb is cynically hawking our stolen property purely for profit and in violation of U.S. law,” he said.

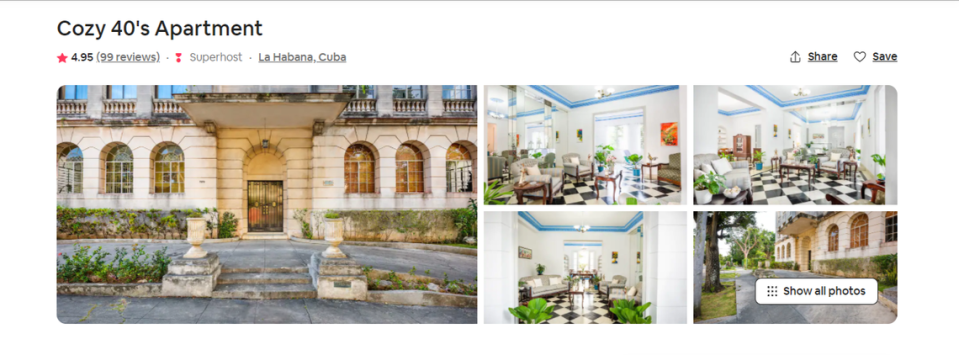

The Airbnb rental, described by guests as “beautiful,” “terrific,” “gorgeous” and “classy” in a hundred enthusiastic reviews, is one of the six apartments in a building built by García-Bengochea’s family in 1939. It is located in a leafy, quiet area at Avenue 33 in Marianao, a Havana neighborhood. He inherited the claim to one-third of the land and building from one of his cousins, Alberto Parreño. Because Alberto was an American citizen at the time of the confiscation, his claim was recognized by the Department of Justice’s Foreign Claims Settlement Commission, which valued his loss at $66,666 in 1960 dollars.

García-Bengochea detailed his claim in a letter he sent to Airbnb in August 2019 in which he quoted a section of the 1996 Helms-Burton Act that prohibits companies from engaging “in a commercial activity using or otherwise benefiting from confiscated property … or profits from trafficking by another person.”

The company never replied to him, he said. It continues booking the apartment at $107 a day. According to guest reviews, the apartment has been advertised on Airbnb at least since February 2017. The neurosurgeon said that Airbnb has also listed other apartments in the same building over the years.

Airbnb said in a statement that the company “takes allegations such as these very seriously and conducts a thorough investigation when we are made aware of any claims. If we determine that a listing is in violation of our policies, we will take action, which can include removing the listing and Host from our platform.”

García-Bengochea was not much luckier with the State Department.

He notified the State Department in 2009 that the federal agency was renting a 7,000-square-foot penthouse in a building his family owned in Miramar. García-Bengochea inherited the property from another cousin, Desiderio Pareño. Because Desiderio was not an American citizen at the time of confiscation, his claim was not certified, just like those of thousands of Cuban exiles.

But García-Bengochea sent State Department officials documents asserting his ownership of the building. He said he had multiple exchanges with State officials and met with them at least four times with his lawyer. Still, he got a “We don’t do that” answer to his request for compensation, he said.

So the agency continued paying rent, but to the Cuban government, until 2019, he said. Reportedly, State had been leasing the apartment since 1978 as a residence for American diplomats in Havana. An independent real estate appraisal commissioned by García-Bengochea in 2016 estimated the rent he is owed at $2.6 million.

“The United States government’s position is that the confiscations of private property in Cuba were illegal under international law and ‘wrongful.’ Yet, knowing everything in Cuba is confiscated, State benefited from [exploiting] our property for 40 years while refusing to compensate the rightful owner,” García-Bengochea said.

“With what moral authority can our government demand that Raúl Castro recognize the claims of Americans if they themselves are unwilling to do so?” he asked. “This is an untenable position, the height of hypocrisy and wrong. It is disgraceful.”

A State Department spokesperson confirmed that the agency has engaged with García-Bengochea several times. Asked why it continued renting the apartment for years after notification, the spokesperson replied in a statement: “The Department is not currently renting this apartment.”

The agency did not say why it didn’t compensate him.

“The Department takes seriously any allegation of trafficking in confiscated property, and we carefully consider the best ways to support U.S. nationals’ claims,” the statement reads. “The Department is committed to upholding the law.”

Why García-Bengochea’s family real estate assets turned into profitable businesses — just not for him — has much to do with the fact that the claims to properties confiscated without compensation by the Cuban government, including the 5,913 certified by the U.S. Department of Justice, have never been settled. Under a brief detente, the Obama administration pursued talks with the Cuban government, but they went nowhere.

And the legal path that the Helms-Burton Act provides to seek compensation has turned out to be tortuous, expensive and full of challenges.

In 1996, Congress passed the Helms-Burton Act to, among several other goals, allow the owners of those properties, including naturalized Cuban nationals, to sue companies from any country, including the U.S., that was benefiting (“trafficking”) from them. But successive presidents suspended a key provision, Title III, that allows the lawsuits to proceed in court, fearing diplomatic conflicts over the law’s extraterritorial reach.

Fast-forward 23 years. President Donald Trump lifted the suspension, opening the gate to the 42 lawsuits filed so far. But then, the text of the law itself and its interpretation have posed further challenges for Cuban Americans like García-Bengochea, who inherited the claims to confiscated property in Cuba after the law passed in 1996.

After advocating for several years for enforcing Title III, García-Bengochea filed three lawsuits against cruise companies Carnival, Norwegian and Royal Caribbean, which offered cruises to Cuba with a stop at Santiago de Cuba, the island’s second-largest city. He inherited from his cousins La Marítima Parreño, the commercial shipping port and warehouses in Santiago de Cuba. A portion of that claim is also certified.

In court, the companies have argued that since the Helms-Burton Act, also known as LIBERTAD Act, precludes lawsuits of those who “acquired” the ownership of the claim to a confiscated property after 1996, his case lacks merit.

His case is still on appeal, but another plaintiff, Robert M. Glen, has already asked the Supreme Court to weigh in to reconsider that interpretation of the law, which effectively bars most lawsuits, as the majority of the original owners have died.

The cruise companies have also argued that their activities are covered by an exception in the Helms-Burton Act authorizing transactions and “uses of property incident to lawful travel to Cuba, to the extent that such transactions and uses of property are necessary to the conduct of such travel.” What lawful travel and “necessary” mean in that context have also become a subject of controversy. The Eleventh U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta, where García-Bengochea’s lawsuit against Carnival is under consideration, invited the U.S. government to clarify the meaning of several terms in the law.

Is your family name on this list? Time to sue for property lost in Cuba might run out

But many believe the U.S. government should do more to achieve a permanent solution for holders of certified claims.

“Extraterritorial lawsuits are a huge investment. Americans should not be forced to litigate a matter that should be resolved diplomatically,” said Jason Poblete, a D.C. lawyer and long-term Cuban watcher. “Helms-Burton is a tool, a useful but flawed tool.”

Florida Republican Sen. Marco Rubio also wants the Biden administration to be more aggressive in holding American companies accountable for doing business in Cuba with confiscated property.

“Any American company that illegally enriches itself through properties confiscated by the Castro regime is violating U.S. law and must be held accountable,” Rubio said. “It’s not the first time Airbnb has encouraged travel to locations known for human rights abuses and even genocide. Even though the Biden Administration has shown zero interest in truly standing with the Cuban-American community, it should enforce U.S. law and punish those companies engaged in similar practices.”

The Biden administration recently fined Airbnb for apparent violations of the embargo in an unrelated case. Airbnb self-disclosed the violations, which were regarded as “non-egregious” by the Treasury Department. But the agency warned companies about doing business with Cuba without taking into consideration the risk of potential sanctions violations.

Asked to comment about the Biden administration’s efforts to settle the claims and its views on American companies’ commercial activities involving confiscated property in Cuba, the State Department’s spokesperson said: “We understand property claims against Cuba, as well as Titles III and IV of the LIBERTAD Act, have long been controversial, both with our international partners and with some Americans who seek compensation for the Cuban government’s confiscation of their property. The administration is carefully considering the best ways to support U.S. nationals’ claims.”

To García-Bengochea, reaching a permanent solution to the claims is a matter of time.

“Unless the claims in Cuba are settled, there will never be clear title to property, without which capitalism cannot function, much less be transformative,” he said. “Absent these, few global companies would consider new investment in Cuba as we’ve seen. The fact is the claims are by far the core issue in the Cuba saga, and with each passing year, a resolution will become more onerous for the dictatorship and their partners, to the profound detriment of the Cuban people.”