From catastrophe to collaboration: Spring Creek Flood spawns volunteer weather network

A tragic night in Fort Collins 26 years ago birthed what grew into the single largest daily precipitation network in the U.S.

The July 1997 Spring Creek Flood killed five people, injured 54 and caused millions in damages.

The catastrophe turned into a grassroots collaboration that served as impetus for the creation of the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network, which has grown from its humble Fort Collins beginnings into 26,000 volunteer citizen scientists across the country and beyond.

“I had never seen a storm like that in my entire life," said Nolan Doesken, Colorado's state climatologist at the time and founder of CoCoRaHS.

A storm like none other floods Fort Collins

It wasn’t just the copious amount of rain that caused one of the city’s most damaging natural disasters July 27-28, 1997, but also the wide variance in rain received across the city.

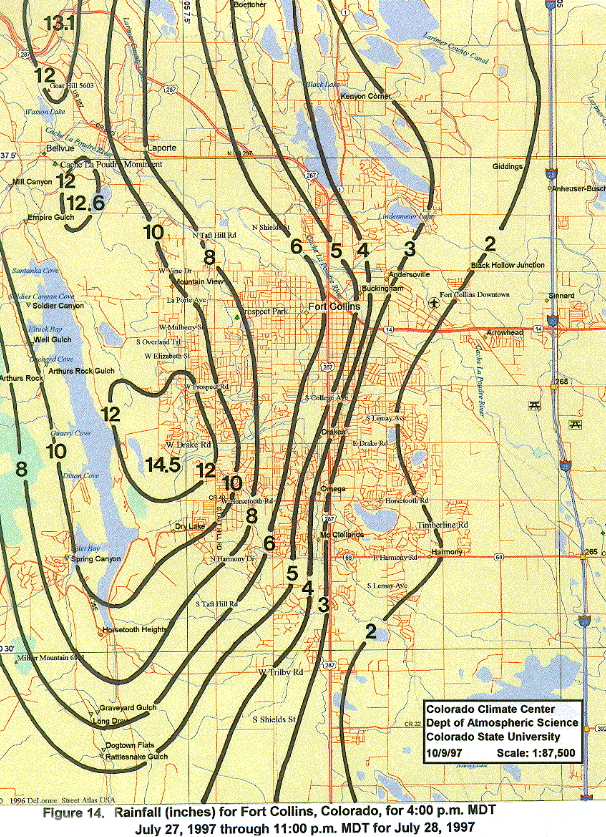

Western parts of the city saw more than 14 inches of rain in 31 hours, while the center of the city saw 6 inches and eastern areas 2 inches. The 14.5 inches was nearly as much precipitation as the city sees in an average year.

But those measurements weren’t known because there wasn’t a way to reliably measure torrential rains in Colorado, Doesken said.

“The state had just completed a study of extreme rain events at the time," he said. “The conclusion was we didn’t for sure know how much rain fell during past storms producing rain that creates flooding. I felt this was my chance."

Shortly after the deluge, Doesken and others went door to door, combing neighborhoods for anybody who had rain gauges, paint cans, buckets, old tires and anything else that held rainwater to try determine how much rain fell.

Local meteorologist Jim Wirshborn had a number of observers who kept measurements, but those were mostly located on the east side of the city, which saw the least amount of rain.

Doesken had colleagues who had rain gauges in the western part of the city for more pieces of the precipitation puzzle. But Doesken discovered his own rain gauge was cracked, rendering it useless.

Despite living in the northwest part of Fort Collins, he didn’t know the Laporte area received more than 10 inches of rain the night of July 27.

“Here at my house, we have an irrigation ditch by the barn and it was overflowing with water and we didn’t know where it was coming from; it didn’t make sense," he said. “People were blaming the irrigation company, but they weren’t at fault — the water was floodwater flowing perpendicular to the ditch.’’

This was only the beginning; July 28 was way worse

Already saturated ground was quickly overcome as copious amounts of rain continued July 28, especially on the far west side of Fort Collins.

Much of that rain drained into Spring Creek, swelling the normally 4-foot-wide waterway quietly winding through the middle of Fort Collins into a much wider torrent.

Debris in the flood water clogged a railroad underpass, which caused water to back up just west of the Johnson Mobile Home Park along the creek west of College Avenue. As the floodwaters grew, it topped over then blew out the embankment sweeping railroad cars with it as it ripped through the mobile home park and killing five people in the area.

The water spread to the Colorado State University campus, causing $140 million in damages, and other buildings around the city, totaling more than $200 million in damages citywide.

Doesken said the floodwaters were so deep at the city’s official weather reporting station — near the lagoon on the main CSU campus — that the station was underwater a portion of the night. Water reached the bottom of the rain gauge 2 feet off the ground.

Without reports of heavy rain occurring, the National Weather Service was unable to warn residents of the impending doom the flood unleashed.

“The 1997 flood made us realize that radars at the time really did a bad job of rain estimation ... especially with this storm," said Russ Schumacher, professor in CSU's Department of Atmospheric Science who succeeded Doesken as state climatologist. “This was such a different type of storm; this was more of a tropical storm.’’

Spring Creek Flood of 1997: Relive one of Fort Collins' most tragic event

Lack of widespread use of email, internet, web-based mapping hinders rainfall reporting

To help with rainfall reporting immediately after the flood, Doesken and others reached out to the Coloradoan, area radio stations and large employers with extensive email lists such as CSU, Poudre School District and Hewlett-Packard, asking people to send in rainfall reports.

“In 1997, people had email, but it was not widely used, so we had to look at other ways to get the word out we were looking for rainfall reports," Doesken said. “As we started getting reports, I kept notes on contacts, locations of the rain amounts and how much rain they received and determined the reliability of the reports.

“Then we would record the data on a map we had hanging on the wall. That’s how we did it back then."

That information helped create the concentric rainfall circles used to measure the wide-ranging rainfall totals around the city.

Just months before the flood, Doesken had enlisted the help of one student at each of the three high schools in the city at the time — Poudre, Rocky Mountain and Fort Collins — to test a project equipping volunteers with foil-covered plastic foam pads to improve hail data collection in Colorado.

Hail doesn’t happen nearly as much as rain here, which prompted one of the high school students to raise a valid question that redirected the effort toward rain measurement.

“By the time it hails, we will have forgotten what you asked us to do,'' the student said, according to Schumacher. “Wouldn’t it be better to have volunteers involved in something that can give them something to do more often?"

Doesken changed gears from hail to rain, but there was another technological problem. His goal was for volunteers to send in daily rainfall reports and for results to be seen on a map the same day.

“The problem was web-based data collection was new and I wasn’t sure our department was ready do it," Doesken said. “I knew high school kids were getting into the internet thing and so it didn’t take long with the help of HP to trust high school students to build it."

Doesken said one of the students built the initial data collection map on which reports were logged in a couple of weeks.

“Once people could see their data the same day they reported it, it turned the whole project alive," Doesken said.

Community Collaborative Rain, Hail & Snow Network is as grassroots as it gets

By spring 1998, with a small grant from the Colorado Office of Emergency Management and help from Fort Collins Utilities, the site was built.

Another student recruited family volunteers from each of Poudre School District's 40 elementary, middle and high schools at the time to record rain. Later, hail and snow were added to the reporting.

Then, as luck would have it, a public service announcement asking for volunteers was aired on a local radio station playing music from the 1940s and 1950s, and many retirees listening to the station responded, Schumacher said.

On June 17, 1998, the first version of the CoCoRaHS website went live. Rain and hail measurement training followed.

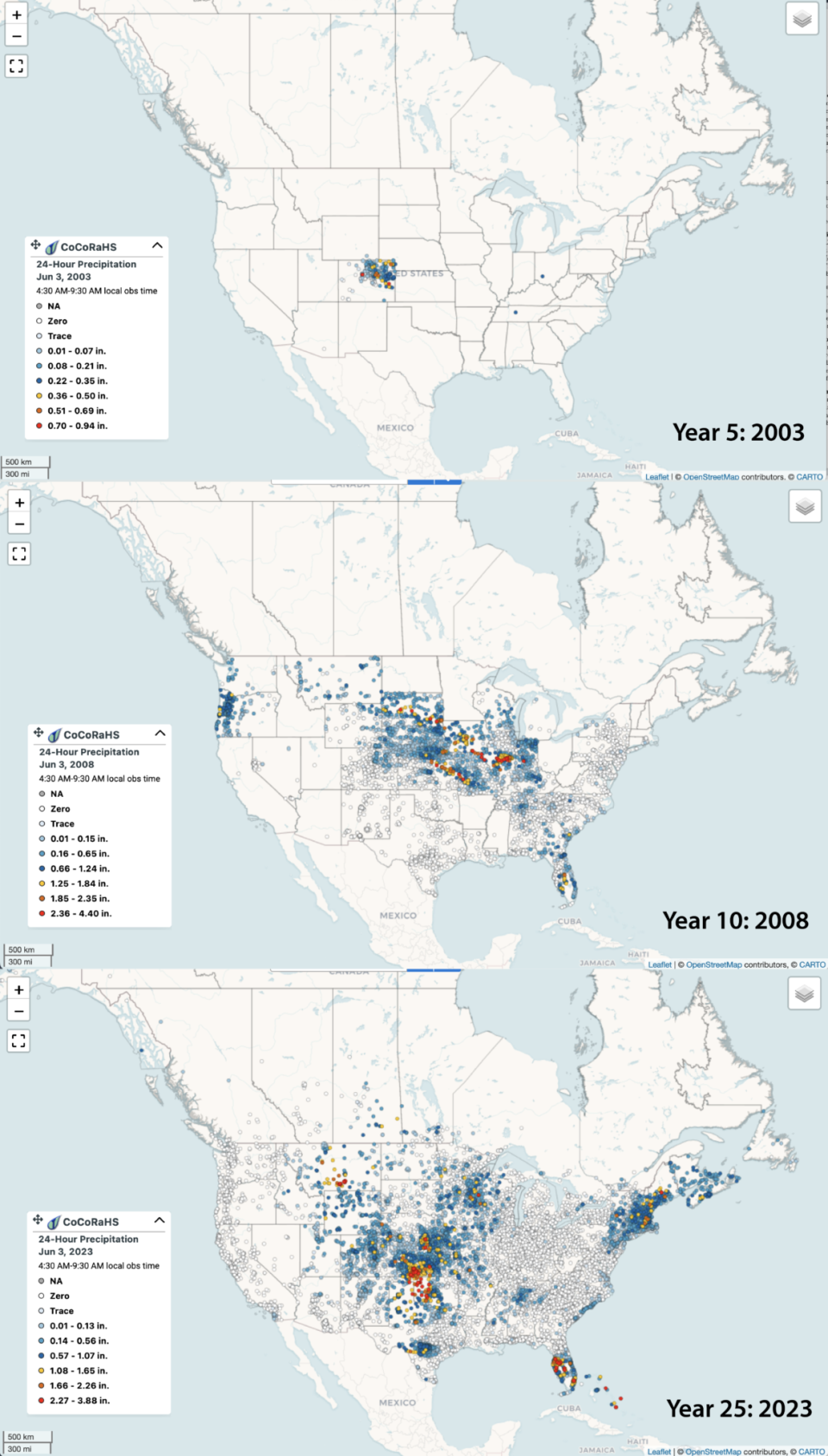

In 2003, another major step was taken when Henry Reges became the national coordinator of CoCoRaHS and took the network national.

The rain gauge map now looks similar to cell service maps during commercials showing coverage of the country.

Minnesota became the 50th state to join in 2009. Volunteers from Canada, the Bahamas, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, have since joined. Guam was added in 2022.

In 2015, one of the network's gauges was placed in the White House vegetable garden.

“We weren’t sure we were ready for it to go national," Doesken said. “I still don’t think I thought it would turn out to be as big of deal as it has become."

Over the past 25 years, the grassroots network has come a long way.

It's sold T-shirts, rain gauges, rain gauge calendars and Nalgene water bottles to help fund it, held hail pad-making parties and talked to people from farm shows to weather festivals.

It holds an annual March Madness event where it challenges states to recruit the most volunteers. The winner is awarded the CoCoRahs Cup.

And all that data is now used by the National Weather Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, hydrologists, water managers, farmers, researchers and the insurance industry, among others.

“It all started right here in Fort Collins and now you can see the legacy around the country," Schumacher said. “We ask people to take all these measurements daily and to support the network financially and it’s amazing to see how it has grown. That’s the vision Nolan had."

How to sign up to become a Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow volunteer

Sign up at www.cocorahs.org to provide your location and contact information.

Obtain a plastic 4-inch rain gauge. Cost is $33 plus shipping and handling. Information on where to get one can be found at www.cocorahs.org.

View the online training materials at www.cocorahs.org.

Setup your gauge in a good location. (See tips on where to install your gauge on the CoCoRaHS site.)

Begin measuring precipitation and send in your reports each day.

This article originally appeared on Fort Collins Coloradoan: Fort Collins' 1997 Spring Creek Flood spawned CoCoRaHS weather network