A ‘Catch Me If You Can’ Wannabe’s Very Long Con

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“The fraudster is not usually in Beverly Hills.”

That’s what Kevin Edmundson, then a lawyer for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, thought in 2007 when he met Mark Roy Anderson at his office on Wilshire Boulevard. The office, inside a bank building, was not “grand,” Edmundson recalled, but it was blocks from Rodeo Drive in one of the most luxurious neighborhoods in Los Angeles County.

Edmundson said he went to California to interview Anderson after the SEC slapped him with a civil suit alleging he swindled $1 million from a Dallas real-estate broker and other investors by selling thousands of shares in an oil company. Despite a slew of enthusiastic emails about a “huge oil well” in Nevada, Anderson never delivered the promised economic returns to investors, the civil complaint states.

“I just remember being on Wilshire Boulevard in Beverly Hills and thinking ‘What is this guy doing?’” Edmundson told The Daily Beast recently. “I mean, he’s supposed to be in a strip mall, somewhere—I don’t know, in Vegas.”

To Edmundson’s surprise, Anderson amiably escorted him inside his mostly empty office, to a table in the center of the room. In the first of many conversations, Anderson was seated comfortably, wearing a button-down shirt and slacks as he refused to plead the Fifth—but still “played possum” with the SEC attorney, offering vague and insubstantial answers to questions about the case.

“I think he believed he could talk himself out of a civil lawsuit brought by the SEC. And I just remember thinking that this guy is incredible and I can’t believe he had agreed to meet with me,” Edmundson recalled. “He ought to be smart enough to know whatever he tells me, I’m going to walk that down to the FBI.”

And that’s exactly what Edmundson did, sparking a criminal investigation that ended with Anderson’s conviction and a $130,000 judgment against him in the SEC case. Among the victims, according to two people and a 2012 interview with the FBI, was Bryan “Birdman” Williams, the founder of Cash Money records and mentor to rapper Lil Wayne.

As it turned out, the oil investment scheme was not Anderson’s first con job—nor, allegedly, his last.

SEC lawyer Kevin Edmundson (left) sparked the criminal investigation that ended with Mark Roy Anderson’s latest conviction.

On the surface, Anderson does not fit the profile of a career hustler. He has a law degree and was on the business advisory council of the National Republican Congressional Committee. He is the father of five children from two different marriages. He plays the guitar. He goes to Coachella.

“He is incredibly brilliant and talented. He is a true Renaissance man,” one family member, who wished to remain anonymous, told The Daily Beast. “But he also has incredible delusions and, sometimes, makes you believe it.

“The movie Catch Me If You Can always resonated with me,” this relative added, referring to the film in which Leonardo DiCaprio played the chameleon-like con artist Frank Abagnale Jr. “You love him and you are rooting for him, but he is just cuckoo.”

Prosecutors have a less romantic view. They say that over the last three decades, Anderson duped dozens of investors for personal enrichment. He has been convicted at the federal and state level four times for these rackets. After his 11-year sentence in the oil scheme, authorities say, Anderson did not even wait to complete his supervised release before jumping into his next grift.

The Hemp Farm Scheme

Last month, Anderson, 69, was arrested and indicted by the feds for allegedly bilking at least $9 million out of investors who believed they were sinking money into his hemp business. The complaint alleges that Anderson, posing as a third-or-fourth-generation farmer, told investors their money was being used to process his farm-grown hemp into medical grade CBD.

In reality, Anderson did not own a hemp farmstead and duped Oregon farmers into giving him herb he claimed he would turn into CBD, according to the complaint. As Anderson was dodging questions from investors and farmers, prosecutors say, he was also living the high life.

The complaint alleges that between 2020 until his arrest, Anderson spent $650,000 on vintage and luxury cars and $13,000 on private jets. In September 2020, property records confirm, Anderson bought a $1.3 million gated, three-bedroom home in Ojai's East End. A listing for the home boasts an upgraded kitchen, a private well, and a fire pit area—in addition to a sprawling citrus grove with over 15 usable acres.

Anderson also spent $142,000 on shopping sprees at Nordstrom, Pottery Barn, David Yurman, Sephora, Ferragamo, Williams-Sonoma, and Crate & Barrel, according to the complaint. He spared no expense when eating out; court documents detail a $2,500 meal at Rainbow Bar & Grill, about $8,900 in Via Alloro dinners, and two trips to Larsen’s Steakhouse for $1,400.

Now, though, the Orange County jail commissary is the best he can do. Anderson has pleaded not guilty and is being held without bail pending a trial scheduled for February; a conviction could land him in prison for 20 years. His lawyer, Brett A. Greenfield, denied The Daily Beast’s request for comment. The Department of Justice also declined to discuss the “pending and an ongoing investigation.”

But others who have tangled with Anderson over the years are less reluctant to talk.

The Historic Buildings Grift

Raoul Fima says that when he first met Anderson in the late 1980s, they hit it off.

“He was very intelligent and well educated,” Fima, who at the time was a representative for an Italian marble company, told The Daily Beast. “He said he was an attorney and he said that his expertise was buying and selling property. And that interested me.”

Fima said that Anderson asked for a bid on marble for an $11 million building he claimed to own in the coastal town of La Jolla, California. The deal fizzled, but Fima said that he was impressed by Anderson. So, when Anderson later pitched him on investing $175,000 in the building project, he readily agreed and then wrote another $400,000 check to Anderson for an investment in a Beverly Hills building he said he owned.

It took months and a surprise trip to one of the buildings for Fima to realize that Anderson was not telling him the full story. He said when he met the actual owner of one of the buildings—which hit him like a “bolt of lightning”—he ran to a phone booth and called Anderson, who claimed he had already sold the building and that they had made money.

Of course, Anderson said, he had immediately put the proceeds into developing another building. Then Anderson began avoiding Fima’s calls and requests for legal documentation. Fed up, Fima went to the FBI “in person to file a criminal complaint against Mark.”

“At the time I didn't know the feds were already investigating Mark about other investors,” he told The Daily Beast.

According to prosecutors, between 1983 and 1986, Anderson executed a Ponzi-style scheme to defraud investors in what they believed was a partnership to purchase and rehabilitate historic buildings across the country. The buildings he claimed to be renovating included the Fox Theatre in Oakland, California, and the Firestone Building in Kansas City, Missouri.

According to prosecutors, between 1983 and 1986, Anderson executed a Ponzi-style scheme to defraud investors in what they believed was a partnership to purchase and rehabilitate historic buildings, including the Fox Theatre, across the country.

Court documents allege that he formed “approximately 20 limited partnerships involving about 2,000 investors, following which he commingled funds from the various projects and diverted funds from one project to pay for another.” In his pitches to investors, Anderson falsely claimed he was a California attorney. (The Nevada State Bar says that Anderson was admitted to practice law there 1981 and was disbarred 12 years later.)

In 1994, Anderson pleaded guilty to mail fraud, agreed to pay $6.8 million in restitution, and was sentenced to 84 months in prison. Prosecutors estimated that the total loss to investors was more than $47 million.

“He raised a lot of money to buy and refurbish, but ultimately he didn’t do either,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Jean A. Kawahara told the Los Angeles Times at the time.

While he was operating his Ponzi scheme, prosecutors say, Anderson committed several other crimes. He was charged and pleaded guilty to grand theft, preparing false evidence, and attempted grand theft for stealing money from other victims who invested in a building he lied about owning. For these, Anderson was sentenced to four years in state prison, which ran consecutively with his prison time.

He was hit with a third conviction around the same time after he falsified documents to secure a $120,000 mortgage loan and was sentenced to 32 months in jail to run consecutively with the other two prison terms.

“I have to hand it to him, you have to have some degree of intelligence to pull this stuff off. And he was good at it,” Fima said. “But thinking back, he did have a sense of superiority to him, like nobody is fooling him.”

The Oil Scam

It didn’t take long for Anderson to bounce back when he was released from prison in the early 2000s.

“Anderson started a chain of eye-surgery centers, a business that collapsed after his business partner was arrested for health-care fraud,” prosecutors say in the latest complaint.

One of Anderson’s family members remembers that coming up with new ventures was never his problem. The problem was whether the businesses were legit.

“In his mind, he described it as any of the businesses he was coming up with was a game changing, super innovative, really impressive thing,” the relative added. “Some of it sounded really fantastical to me so I always took it with a grain of salt.”

Entertainment consultant Rhonita Thornton wishes she had been more skeptical when Anderson was telling her about a fantastic oil investment opportunity around 2008. Thornton, who said she met Anderson through a music producer who told her the ex-lawyer wanted to “get into concerts,” found him “just too likable.”

“Mark could talk himself out of everything. There was nobody that didn’t like him,” Thornton said. “So when he said he had another venture I would be interested in, I didn’t see why not.”

“It turned my life upside down. I was having a nice life before I met him,” she added.

The venture, prosecutors say, was a scam. Between March 2006 and November 2010, Anderson promised investors he would put their money into several oil companies and similar projects. Instead, he stole more than $9 million from more than 20 victims—and used their money for personal expenses.

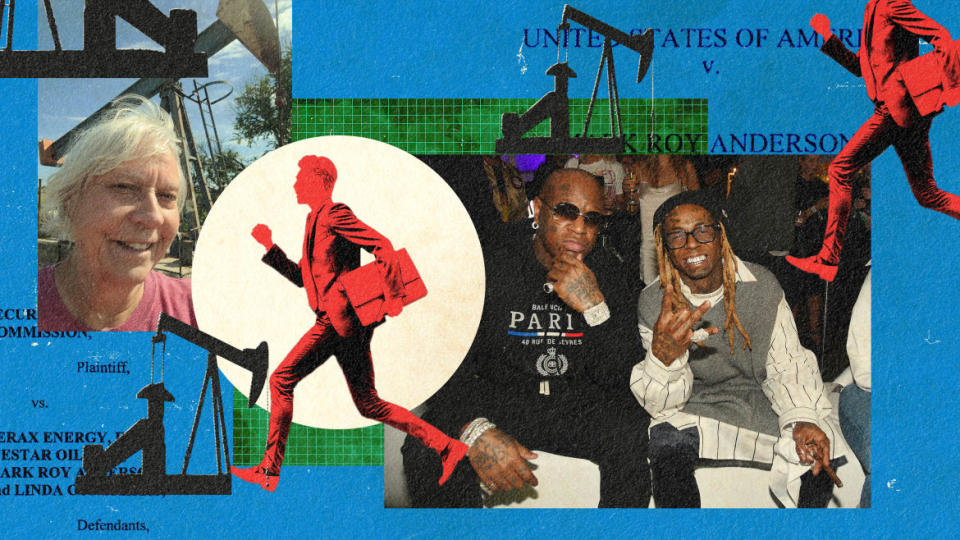

Among the victims, according to two witnesses who spoke to The Daily Beast and a 2012 interview he had with the FBI, was the record label executive “Birdman” Williams, who is referenced in a 2011 complaint as “B.W.”

Williams started Cash Money Records in the 1990s with his brother, Ronald “Slim” Williams and would go on to rep Nicki Minaj, Lil Wayne, and Drake. According to a cached version of their website, the brothers also formed an oil and gas exploration company in early 2010—aided by Anderson, according to a 2012 interview Williams had with the FBI.

Williams, his manager, and his lawyer did not respond to multiple requests for comment. But the 2011 complaint says that Anderson met B.W. in early 2008 and told him about an opportunity to invest in oil rigs in Oklahoma, “which would provide huge returns in a short period of time.”

Based on Anderson’s pitch, prosecutors say, Williams wired Anderson about $5.4 million between April and September 2008. That July, Thornton said, Williams arrived in a Cash Money Records tour bus to Skiatook, Oklahoma, to check on the investment himself.

“We got looks for sure,” Thornton said, noting that she knew Williams prior to the investment opportunity. “We actually went up to the wells. They gave us a whole tour of the area. Mark was showing us the wells and saying that they were ours.”

Skiatook is a small rural town about 20 minutes outside of Tulsa, home to some 10,000 people and 20 churches. It was founded nearly two centuries ago as a trading post by the Cherokee Nation chief and is nestled between two Native American reservations. It was also once a major natural gas and oil production hub in the Sooner State.

Williams told the FBI he met Anderson in Oklahoma “specifically to see the oil leases” he intended to buy, the interview summary states. There, Williams said, he saw “active oil pumps on the land” and believed that the millions he later gave Anderson were for oil leases on the same land.

Nona Roach, who helps oil and gas operators broker leases with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), told The Daily Beast she was with Williams and Thornton that hot July day at the oil fields at Anderson’s request.

Among Anderson's oil investment scam victims was Nona Roach, who works with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and Bryan “Birdman” Williams, the founder of Cash Money records and mentor to rapper Lil Wayne.

“Anderson made them walk all the way to the wells to see the pump jacks in the field,” Roach said. Her first clue Anderson “knew nothing about the oil and gas business” came after one of the guys on the tour played a trick on him and opened up one of the valves of the gas well. The pressure made a loud noise and scared every non-oil expert in the group, including Anderson, she said.

“Elbows and assholes were running towards us!” Roach laughed.

After the group left Oklahoma, Roach said in a 2012 interview with the FBI, Anderson asked her to help him secure more oil leases. Roach, however, said that Anderson had still owed her money from her previous oil lease work. Then, she said, she started to get suspicious of him when he started making excuses about money.

Roach said she ended up filing a complaint with Indian Affairs against him. Later, she helped federal authorities build the case against him.

“This guy's a big fake,” Roach said. “He really thought he was way smarter than anyone else.”

In a summary of Williams’ interview with the FBI, the record executive said he also came to realize that Anderson’s big talk “was a game.” Thornton said that in addition to losing her relationship with the Cash Money founder, she is still out the $500,00 she says she gave Anderson.

“He is a true chameleon,” Thornton said, echoing others hoodwinked by him. “Mark is incredibly gifted at the art of the con. He is like that guy in Catch Me If You Can.”

The Apology

After copping a plea to money laundering and wire fraud in 2011, Anderson sent a handwritten letter to Federal Judge Percy Anderson to apologize “for the pain and suffering” he caused.

“I am willing to give my last years of my life as payment for my sins,” he wrote. “I am incompetent and inept in dealing with money and especially in dealing with others money. I am a fool for pretending that I knew more than I did.”

Anderson described his past as “a very deep scar” and wrote that the first time he went to prison it was “a horrible experience” that cost him his marriage, his possessions, and his self-respect. Around the time he hatched the oil scam, he wrote, he began to “drink too much” ended up in downward spiral that worsened as he lied to investors who wanted to see returns he could not provide.

“I kept hoping things would get better but it only got worse. The mistakes were mine,” he said. “I am damaged and broken. I am a failure, a fraud and an embarrassment.”

Anderson’s brother, Stan, wrote a letter asking for leniency, noting that his disgraced sibling served as the co-chairman “on the business advisory council of the National Republican Congressional Committee” and was “recognized for his dedication and commitment and received the highest honor from George W. Bush Presidential Victory Team.”

Anderson’s wife also wrote a letter to the judge in 2012. She said she admired how Anderson was with his family and how their sons miss their father. But the judge did not heed his family’s pleas, and sentenced Anderson to 135 months in prison and three years of supervised release.

Crop Mark

Anderson’s current chapter began just like his others—with a pitch and personal charm.

Prosecutors say Anderson began hatching a plan almost immediately after he left his 6-by-8 cell in May 2019, while he was still in home confinement in Los Angeles and banned from engaging in any business involving loans.

It was not until April 2020 that Anderson began telling investors a story about a family hemp farm in Kern County, California.

To several investors, Anderson described himself as a generational hemp farmer who had created a company called Harvest Farm Group to help their business, the May 2023 complaint alleges. He tried to sell them a seemingly lucrative opportunity: invest in his vision to plant, grow, and harvest hemp to convert into medical grade CBD for mass distribution. He also told other investors he was “bottling and selling hemp-derived products, such as CBD-infused olive oil and pain cream,” according to the complaint.

Anderson was arrested and indicted by the feds for allegedly bilking at least $9 million out of investors who believed they were sinking money into his hemp business.

To bolster his story, Anderson allegedly claimed to have three “extremely profitable” hemp harvests under this belt and the machinery to convert the herb into a psychoactive strain called Delta 8. He even provided pictures and videos of his purported crop, which two investors would later allege were stock images.

When the returns never materialized, Anderson began to feel the pressure of mounting questions from investors. That desperation, prosecutors allege, may have prompted him to start “some type of hemp ‘business’ in which he was processing hemp stolen from Oregon farmers.”

According to several farmers, Anderson promised to turn their hemp into CBD and share the profits. One sixth-generation farmer sent two shipments but got nothing but unanswered calls and excuses.

That farmer decided to take matters into his own hands and went to California to search for his missing hemp, finding 39 bags of it in “an open field, deteriorating and damaged by the sun” behind a John Deere dealership, the complaint says. The investors later learned the address of Anderson’s supposed farm was an unrelated vineyard.

The farmer and two investors, who hired a private detective, found out they had handed their crops and money to a convicted criminal. A lawyer for one of the investors confronted Anderson about his criminal past, and he claimed he wasn’t THAT Mark Roy Anderson, prosecutors say.

The relative who spoke to The Daily Beast said there was one grain of truth in Anderson’s convoluted tale: their family does have a farming history. And they wondered whether that inspired his hemp get-rich-quick operation.

“He really thinks he is this incredibly impressive entrepreneur. And sometimes you believe him,” the family member said. “I don’t know if it’s a brilliance, or an illness, or just delusion. But it is extremely hard to differentiate between fact and fiction.”

Edmundson, a veteran fraud-buster, doesn’t see any innocent mistakes when he looks at Anderson’s history. He only sees cunning and compulsion.

“Anderson is the true definition of a con man,” the retired SEC lawyer said. “And the only way to stop a con man like him is to lock him up.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.