The CDC chief lost his way during COVID-19. Now his agency is in the balance.

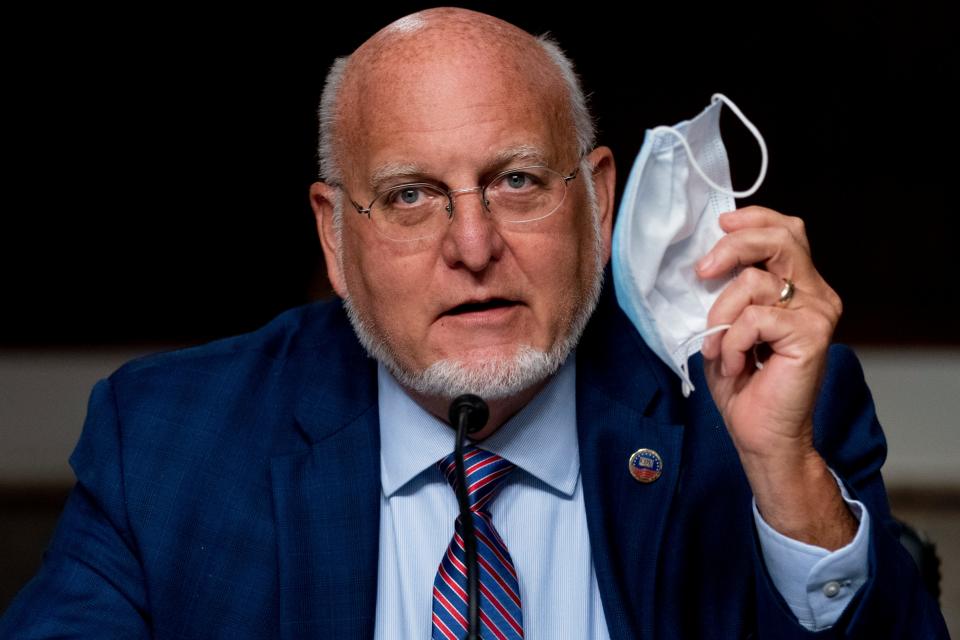

Dr. Robert Redfield, eyes closed and searching for words, explained to Congress why the health agency he leads had softened coronavirus protections for slaughterhouse workers.

The White House, meatpacking industry and other federal agencies were not involved, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention insisted during the September hearing.

None of that was true.

Redfield was sitting in the White House when he instructed his staff to change a series of safety recommendations to suggestions, adding dozens of qualifiers such as “if feasible” and “not required.” He turned to a West Wing aide and told her the edits came directly from Vice President Mike Pence’s chief of staff.

Smithfield Foods, the South Dakota meatpacking plant under scrutiny, had seen the tougher recommendations, one of the first documents outlining COVID-19 protections for the industry. The CDC emailed it the day before the edits were made. Federal agriculture and labor officials also weighed in.

Redfield’s actions in overruling the CDC scientists who had spent a week investigating and writing the original guidance fit a pattern defining his leadership during the COVID-19 crisis. He has repeatedly allowed politics to undermine scientific best practices — and then publicly denied it.

Brett Murphy and Letitia Stein are reporters on the USA TODAY national investigations team. Contact Brett at brett.murphy@usatoday.com or Letitia at lstein@usatoday.com.

The CDC started the COVID-19 crisis as the world’s public health gold standard, a beacon for other countries responding to their own outbreaks. Polls show more than eight in 10 Americans trusted its coronavirus information in early spring, before states across the country began reopening. The agency earned that respect through decades of shielding its scientific independence from the politics of Washington.

Since then, the country’s faith in the CDC’s coronavirus guidance has evaporated by double digits. President Donald Trump has undermined the agency by airing his own mistrust in it. And CDC scientists and staff have increasingly expressed their deep concerns over Redfield’s leadership and the state of the agency.

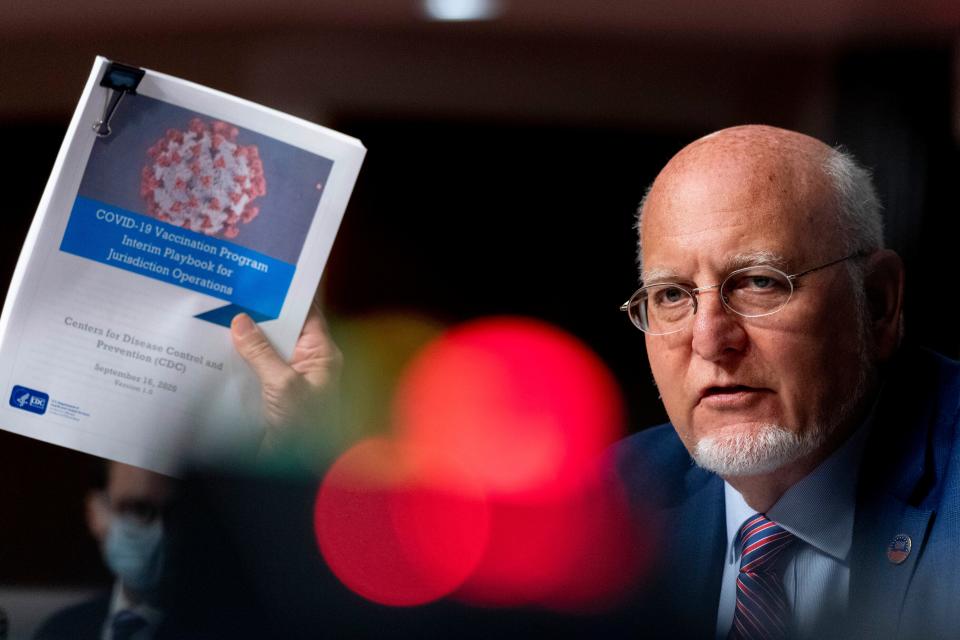

The election of a Democratic president may put a timestamp on Redfield’s tenure. But the CDC’s leadership remains critical during the transition weeks. President-elect Joe Biden moved fast this week to highlight Redfield’s statements that masks will be American’s best safeguard against the virus, even after a vaccine debuts — remarks that had drawn Trump’s ire.

But experts both inside the agency and out fear Redfield’s failures already have irreparably scarred American public health institutions, with life and death implications for a winter surge of outbreaks.

“The integrity of the agency has been compromised,” said former CDC acting director Dr. Richard Besser. “That falls to the director of CDC.”

USA TODAY interviewed dozens of Redfield’s current and former colleagues, as well as his critics, supporters and an array of public health officials. Reporters reviewed internal CDC communications and more than 45 hours of his statements at the Capitol and in television and radio interviews. While Redfield’s capitulation to the White House has received attention throughout the pandemic, this reporting provides the most comprehensive portrait of the nation’s public health leader as his credibility unravels.

Redfield forged his career on the front lines of the HIV/AIDS epidemic as a military doctor. He had aspired to be the CDC director since at least the early 2000s. After landing the post, he seemed on track for success with the launch of a federal initiative to end AIDS.

When a once-in-a-century pandemic exploded this past winter, Redfield, a devout Catholic, told friends that answering the crisis felt like his calling. For 10 months, he has sought a middle ground between staying in the Trump administration’s good graces and promoting the CDC’s science.

Even colleagues sympathetic to his situation now worry that his failures could cast a long shadow over the agency. With each surrender behind closed doors and milquetoast public appearance, Redfield has alienated both his staff and politicians in Washington, records and interviews show.

In late September, Dr. William Foege, a former CDC director famous for eradicating smallpox, urged Redfield to orchestrate his own firing.

“Acknowledge the tragedy of responding poorly, apologize for what has happened and your role in acquiescing,” Foege wrote in a private letter to Redfield first reported by USA TODAY. “The public health texts of the future will use this as a lesson on how not to handle an infectious disease pandemic.”

Climbing cases, waning credibility

The CDC director in the next administration will face a country increasingly distrustful of the agency’s coronavirus information, nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation polling shows. The drop has been especially dramatic among Republicans, whose faith in the CDC declined by 30 percentage points from April to September.

The erosion in credibility comes as the CDC may be needed most: The agency is leading efforts to distribute a COVID-19 vaccine even as infections are surging to record numbers. Virtually all states now are reporting rising case counts.

“When CDC says it, you can take it to the bank. What the administration has done, above CDC, is they have made that suspect,” said Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association. “That is what makes this issue with CDC so corrosive.”

In the most troubling cases this year, Redfield pressured local health officers to grant favors to politicians and businesses, records show. He has allowed political appointees outside the agency to write and publish information on the CDC’s website — sometimes over the objections of his top scientists and without technical review.

Hours before the CDC was to release school-reopening guidelines in August, the White House revised the document’s introduction, downplaying health concerns and encouraging schools to reopen, according to three health officials involved. CDC’s school safety experts did not even have time to read the whole document before it went online.

“We didn’t feel like we had a choice” whether to publish, one of the officials told USA TODAY about the episode, first reported by the New York Times. CDC officials spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the meetings.

Amid the delays and confusion, local politics — not clear scientific guidance — largely determined which students are back in the classroom and which are learning online.

Industry executives and lobbyists have repeatedly called up allies throughout the administration who successfully pushed the CDC into diluting and delaying guidance.

At the urging of cruise companies, the White House pressured the CDC to hold up the agency’s sailing ban in March. Explicit warnings about the duration of the ban were removed from subsequent extensions of the ban. At least four ships cast off in the week before the original no-sail order and went on to experience COVID-19 outbreaks while at sea.

Two federal officials recalled conversations about the orders with a visibly frustrated Dr. Martin Cetron, the agency’s director of global migration and quarantine. Olivia Troye, one of Pence’s former top aides who worked directly with the CDC, remembers Cetron telling her: “We are going to kill Americans.”

Now CDC employee surveys show morale so low that fewer infectious disease experts are willing to volunteer to leave their regular duties and deploy to rural communities, said a senior CDC official with access to the data. The official, like others interviewed by USA TODAY, blames Redfield’s deference to the White House.

“My staff have no respect for him,” the official said.

Under Redfield, political appointees outside the agency started screening the CDC’s weekly scientific journal, used to inform doctors and scientists nationally. Many of his employees, who consider those reports sacrosanct, thought he had crossed the Rubicon.

“You’d expect the head of CDC to forcefully defend our agency,” another senior official said in an interview. “That’s really frustrating for people who have spent their life doing this work.”

After Politico first reported on the interference, Redfield told Congress the journal’s scientific integrity had not been compromised.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this

By most measures, Redfield has been in a nearly impossible position: serving at the discretion of a president hostile to unpopular public health measures. Experts fear the damage done will be lasting, regardless of who leads the agency through the next stages of the pandemic.

“Once the president’s political intervention has been put in place, there will always be suspicion that it can happen again,” said Dorit Reiss, a professor at the University of California Hastings College of Law, who thinks laws should change to protect the CDC’s autonomy.

Though he declined to be interviewed by USA TODAY, Redfield has confided in private that the criticism is weighing heavily on him, despite attempts in public to rise above.

“I try to stand up and say never mind the critic,” Redfield said in a July webcast interview with the prestigious medical journal JAMA, a nod to President Theodore Roosevelt. “The credit goes to the man or woman that’s in the arena all bloodied and marred, tries, comes up short, tries again, comes up short again.”

Redfield has contradicted Trump in his testimony to Congress by supporting masks. After the president called him out for forecasting the dangers of flu season, Redfield kept warning Americans in interviews.

In a rare press conference at the CDC headquarters in Atlanta last month, Redfield spoke only briefly, but used the words “science” and “data” 22 times.

Alex Azar, who oversees the CDC as secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, then rejected the notion that politics had undermined the agency, following a ProPublica report detailing months of interference.

“What comes out of CDC at the end of the day,” Azar told reporters, “is Dr. Redfield’s conclusions around science and evidence, with the support of his team.”

CDC leader faces a reckoning for mistakes

In late June, Azar visited CDC headquarters to meet with senior leaders. During one closed-door session, he laid out the agency’s early missteps: failures in developing a reliable COVID-19 test and in helping states control the first outbreaks.

“There will be a reckoning,” he told them, according to three officials in attendance.

Azar looked to Redfield to respond. Redfield paused, while those in the room waited for him to defend the agency. Then he punted to a deputy instead.

That deflection “took the air out of an entire room,” one of the attendees told USA TODAY.

HHS declined to comment about the meeting. In a statement, agency spokeswoman Caitlin Oakley said the department’s pandemic response has relied on science and “never tried to force any conclusion on the CDC’s data.”

“The American people are fortunate to have Dr. Redfield leading the CDC,” she said.

The White House did not respond to detailed questions but spokesman Brian Morgenstern said the CDC “is a key participant in all relevant policy discussions.”

Yet in the White House’s coronavirus task force meetings, Redfield has struggled to champion the work of CDC scientists.

“The entire task force is full of sharks eating each other,” said one senior health official. “And Redfield is not a shark.”

Others described his approach as professorial.

“He’s calm. Doesn’t lose his temper. Measured. Somebody might interpret that as passive. I didn’t,” former White House advisor Joe Grogan, a member of the coronavirus task force until his departure in May, told USA TODAY. “You have to pick your battles in a room with 30 people.”

Redfield, 69, had never run a large government bureaucracy when he was appointed in March 2018 to direct the CDC. The $7 billion agency, which protects against everything from food-borne illness to Ebola, has long seen itself as a scientific entity above politics.

The Trump administration had its own view.

In an unusual move, HHS dispatched political appointees to the CDC’s headquarters in Atlanta, the only major government agency outside of Washington, D.C.

“The CDC guys think that they don’t answer to the president and that they are somehow an independent agency outside of the executive branch just spewing information out into the ether without a policy or political concern,” Grogan said. “There is a disconnect.”

In 2018, Redfield took over an agency roiling from the scandalous departures of two top health appointees: HHS Secretary Tom Price, who had abused government funds for travel, and Redfield’s predecessor, Dr. Brenda Fitzgerald, who was discredited for trading tobacco stocks while in the job.

READ MORE: How the CDC failed public health officials fighting the coronavirus

The white-bearded physician had specialized in HIV/AIDS care. After two decades at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Redfield respected the chain of command. When he was told not to disclose his appointment to the post — a job for which he was first short-listed under President George W. Bush — he did not even clue in his boss, Dr. Robert Gallo.

With Gallo, Redfield had helped to show the disease spread among heterosexuals, and the two men, with another scientist, had founded the Institute of Human Virology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

When they eventually spoke, Gallo said, Redfield explained that leading the CDC could fulfill a real purpose in his life. “He was ambitious to do something globally in public health,” Gallo said.

Science was Redfield’s family’s business. His parents worked at the National Institutes of Health, and Redfield speaks of his father’s work in a biochemistry lab in the 1950s as furthering science even after his early death.

Redfield’s mother, left a widow with young children, continued with laboratory work. She used to pray that her son would become a “real doctor” — which to her meant a laboratory physician and researcher, Redfield said in an audio interview with the CDC Foundation, a nonprofit that supports the government agency.

Redfield wanted to treat patients as well as research their diseases. “I wanted much more immediate fulfillment, so obviously I thought medicine was going to be closer to that,” he said in the foundation’s podcast.

He told Georgetown University’s alumni magazine that the school’s Jesuit tradition shaped his view that “science and medicine are made to impact public health.”

At the CDC, Redfield has embraced his faith, which some colleagues find uncomfortable, others a welcome change. He signs emails with “God bless” and frequently offers to pray with colleagues facing personal challenges.

He has also reminded colleagues that he took a $550,000 pay cut to lead the agency. In academia, he missed having a public service mission. He wanted to modernize the sprawling agency’s use of data, advocate for greater federal funding — and to secure his own legacy.

A father and grandfather, he mentioned this past spring a grandchild with cystic fibrosis in a conservative talk radio show interview, asking all Americans to sacrifice in a pandemic.

“We all now are in this war. We’ve all been recruited,” Redfield told host Todd Starnes in April. “We are all asked to join to save a life, to save the vulnerable. This is what it’s about. This is why we’re doing this.”

‘I remember crying because I knew what those changes meant’

More than 10 million Americans have been infected with COVID-19 — the most of any nation — with deaths hovering near 240,000.

Meatpacking facilities alone account for at least 39,000 cases and 196 deaths. Two incidents this spring showcase Redfield’s deference to politics over protecting workers. In early April, the vice president’s office leaned on Redfield as part of its efforts to help the industry remain open, which placed vulnerable workers in harm’s way.

“We need you to continue, as a part of what we call our critical infrastructure, to show up and do your job,” Pence told beef and poultry workers during a press conference April 7. “You are giving a great service to the people of the United States of America.”

At the same time, the JBS beef facility in Greeley, Colorado, was experiencing one of the worst outbreaks in the state. On April 10, state and local health officials said they wanted to shut down the plant.

The next day, the state health director explained to colleagues that Redfield had called her, telling her to consider the workers critical, despite the health risks identified by his own agency.

JBS had spoken with Pence’s office, which in turn directed Redfield to intervene, according to emails first disclosed by the Denver Post. USA TODAY obtained the emails from Columbia University’s Brown Institute, which has canvassed local agencies for thousands of public records.

Redfield told local officials they could send “asymptomatic people back to work even if we suspect exposure, even with the outbreak at present level,” the state health director wrote.

The local officials agreed. But JBS closed the plant shortly after. To date, at least 290 positive cases have been tied to the facility. Seven employees died.

JBS spokesperson Cameron Bruett said those who died had stopped working in the plant almost two weeks before Redfield intervened.

“Companies in our sector were receiving conflicting guidance from local authorities and the CDC,” Bruett said in an email. “We ultimately made the decision to take more aggressive action than the offered guidance.”

In another case in April, two groups of scientists at the CDC approved a safety report on a massive COVID-19 outbreak at the Smithfield Foods pork plant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

A day later, the CDC issued an amended version of the report to the company and state officials, making explicit that the recommendations — including whether sick employees should stay home and whether dirty masks should be replaced — were “discretionary and not required.” The edits were first reported by MSNBC.

How the CDC failed public health officials fighting the coronavirus

Democratic U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin, whose state of Wisconsin is home to more than 130 slaughterhouses and processing plants, pressed Redfield to explain the changes in the Smithfield report during the Senate hearing in September. He testified that the CDC is not primarily a regulatory agency and insisted the industry and other agencies had not played a role.

“We wanted to make clarification to make sure that people understood ours was a recommendation and not a regulatory requirement,” Redfield said.

Baldwin asked if the CDC had had any contact with Smithfield Foods, the U.S. Department of Agriculture or the White House before the Sioux Falls report was edited.

“No,” Redfield responded. “Not at that time.”

Senators sent letters to the CDC and HHS demanding an explanation. Then Redfield called Baldwin to correct his testimony. He explained that the CDC had, in fact, worked with both the labor and agriculture departments before finalizing the recommendations. His own employees actually had detailed those conversations — including one that took place on the day the second report was issued — to lawmakers in May, according to emails obtained by USA TODAY.

But Redfield did not mention what else had taken place inside the White House.

After the original report was approved, Pence’s chief of staff, Marc Short, relayed editing requests to Redfield in the West Wing, according to Troye, Pence’s former aide. She sat next to Redfield as he dictated the changes to staff over the phone, an episode first reported by the New York Times. Short frequently spoke with executives from Smithfield and other meatpacking companies, Troye said.

The Smithfield pork plant, a sprawling complex of more than 90 buildings, was one of the largest known COVID-19 hotspots in the country this past spring, when about 1,300 workers contracted the virus and four employees died, according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

“I remember crying,” Troye told USA TODAY. “Because I knew what those changes meant.”

In a statement to USA TODAY, Smithfield disputed the number of deaths, saying there were two, not four.

Company spokeswoman Keira Lombardo maintained that the CDC’s original Sioux Falls report was a draft and not yet finalized when changes were made. Regardless, she said the company opted for stronger worker protections than the CDC suggested, including more than $600 million in on-site testing facilities, air purification systems, and shields and masks for employees.

“The aggressive measures we have implemented have proven to be successful,” Lombardo said.

In late April, the CDC co-published guidance with the Department of Labor, which has enforcement powers, for all meatpacking facilities nationwide. That guidance adopted many of the qualifiers from the final Smithfield report. Two days later, Trump issued an executive order urging all food processors to stay open amid fears of food shortages.

Rep. Rosa DeLauro, D-Conn., wrote to Redfield, condemning what she considered toothless recommendations, written in a way that effectively indemnifies employers.

“Such inadequate guidance, coming from our nation’s top health protection agency whose mission is to save and protect lives from health threats, is simply unacceptable,” she said.

The CDC failed to meet an Oct. 12 deadline to provide documentation about the edits to Baldwin and other senators. Recently, she sent a letter to her colleagues seeking a hearing to get all the facts from Redfield, saying, “There is a pattern of dishonesty and a failure to tell the truth from the CDC Director.”

Political fingerprints all over the CDC’s COVID-19 guidance

Evidence of politics shaping the CDC’s coronavirus guidance under Redfield’s leadership has alarmed health experts across the nation.

“Even at the risk of being fired, the CDC director has a responsibility to make sure that the best available science is communicated to the public,” Dr. David Satcher, a former CDC director, told USA TODAY.

Redfield outraged local health officers in early March by personally requesting a COVID-19 test, then in limited supply, for one of Trump’s political allies in Nevada after the Conservative Political Action Conference, records show.

“It wasn’t the protocol,” Dr. Ihsan Azzam, the Nevada chief medical officer, told USA TODAY. “This is a VIP person. We got a call from the CDC director who is advising that we test him for COVID-19.”

In April, HHS — at the behest of Stephen Miller, the architect of Trump’s hardline immigration policies — told the CDC to issue a public health justification for closing the U.S. southern border to Mexico off from asylum seekers, according to four officials involved.

The CDC’s scientists refused, the officials said, citing evidence that COVID-19 already was spreading domestically and Mexicans were not importing the virus.

“They kept pushing that agenda, but we just weren’t seeing the evidence of that,” one of the officials told USA TODAY.

So, attorneys at HHS wrote the order themselves. Cetron, the agency’s director of global migration and quarantine, would not sign it. But Redfield did, according to the officials. The Associated Press, which first reported on the episode, estimates that 150,000 people — including at least 8,800 unaccompanied children — have been expelled from the U.S. since the order went into effect.

In a statement to USA TODAY, sent via HHS, Redfield defended his decision to sign the order. It warns against introducing new outbreaks into the U.S. and cites the risks at immigration facilities along the border, where social distancing and isolation of the sick are all but impossible.

“The data pointed to a public health risk from COVID-19 to the illegal immigrants and [border patrol] employees at the border,” Redfield said in the statement. “I determined it was in the public health interest, at that time, to issue the order and it was a decision I made as CDC Director.”

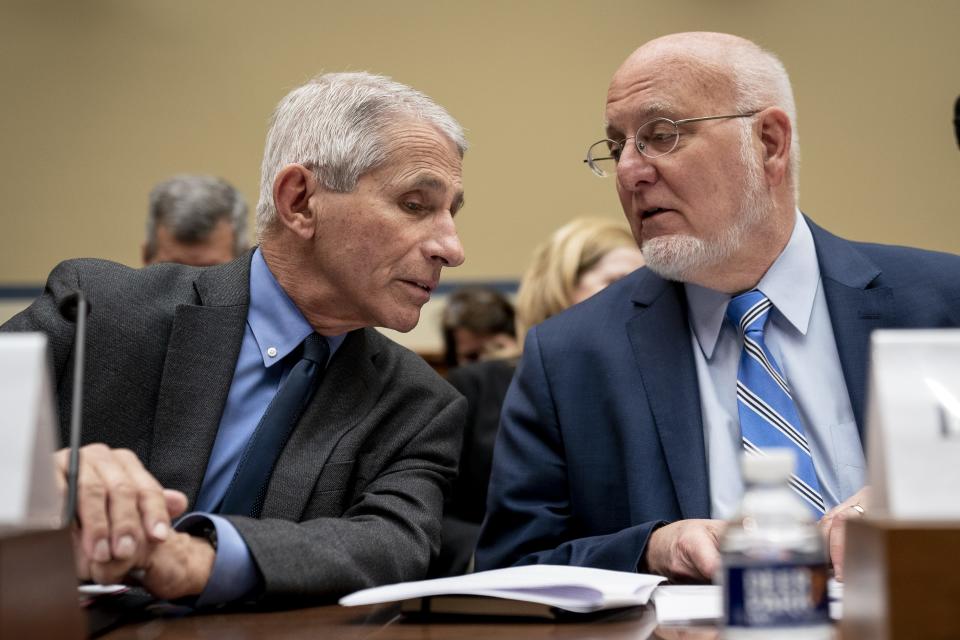

Observers note that Redfield is a political appointee in a post that does not require Senate confirmation. He also lacks the civil service protections of Dr. Anthony Fauci, who has gained fame during the COVID-19 crisis for defending science — and, at times, directly contradicting Trump.

At the start of the crisis, the challenge of Redfield’s position became clear when one of his senior officers, Dr. Nancy Messonnier, warned in February of likely disruptions to American life.

The stock market tumbled, stoking criticism from Trump. Messonnier and other leading agency experts virtually vanished from public view, a striking departure from past public health crises.

Since then, the CDC has held few press briefings. On at least one occasion, Trump has called on Redfield to walk back comments that fell out of line with the administration’s talking points.

“There’s a special gulag,” said Dr. Jeffrey Koplan, a former CDC director, “for truth tellers removed from the CDC.”

The agency also faced political scrutiny at the start of the H1N1 pandemic in 2009. Then-President Barack Obama’s aides questioned the CDC’s recommendations for closing affected schools. A compromise, however, ensured that science would drive the final decisions, recalled Besser, who was then the acting director.

Now, CDC employees say they view the White House coronavirus task force as a black box, where the agency’s guidance goes in one way and mysteriously comes out another. Redfield is typically in the task force meetings without his deputies or subject matter experts.

The Office of Management and Budget has had an outsized role in determining what gets published, according to four federal health officials involved.

In August, many state and local health officers were aghast about the CDC’s abrupt change to its testing guidance: People exposed to the virus but not showing symptoms did not necessarily need to be tested.

The guidance came from HHS, and the CDC posted it over the objections of senior scientists, according to two health officials familiar with the exchange, first reported by the New York Times.

Several weeks later, the CDC reversed the recommendation. When lawmakers later asked what happened, Redfield said the agency had not intended to limit testing. He described his staff as engaged in the document, written cooperatively with other federal entities.

“He wasn’t telling the truth,” said Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Conn., who at hearings has rebuked Redfield for not answering his questions. “Dr. Redfield has become complicit in the White House’s attempts to try to slow down testing and bury the extent of the crisis.”

‘Pattern of ethically and morally questionable behavior’

Questions about ethics and allegiances have dogged Redfield since the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

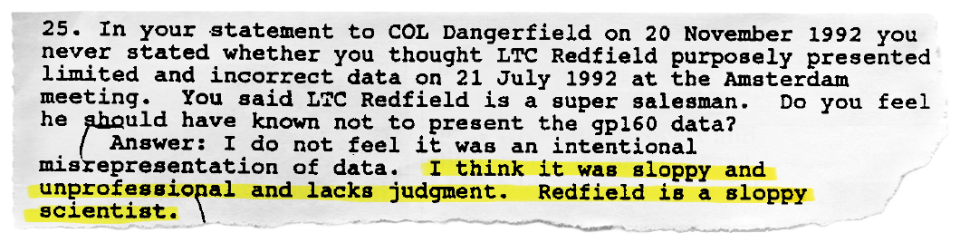

In July 1992, at the height of the crisis in the U.S., Redfield announced a remarkable discovery at a conference in Amsterdam attended by Jonas Salk, who discovered the polio vaccine. Redfield said his military lab at Walter Reed had found a vaccine therapy that showed evidence of reducing the amount of HIV in patients.

Lawmakers, newspapers and medical journals seized on the announcement, hailing a major turning point in the fight against HIV. Congress later fast-tracked millions for more studies at the lab, where Redfield worked alongside Dr. Deborah Birx, now the coronavirus coordinator on the White House task force.

But Redfield’s claims were wrong.

He had presented results from only a portion of patients, not the entire study group, exaggerating the therapy’s effectiveness. A colleague later testified she had provided him with the full data set before the conference. Army statisticians could not recreate his analysis.

“We were like, ‘Whoa, what’s he talking about?’ ” Dr. Daniel Lucey, a major in the Air Force working in Redfield’s lab at the time, recalled in an interview with USA TODAY. ‘“There is no great breakthrough.’ ”

Others who worked in the lab described Redfield as more salesman than scientist, eager to make his mark in the field.

Worried they had been pulled into a public embarrassment, the other scientists held a series of meetings at Walter Reed, where Redfield then agreed the presentation was not accurate, according to five people in attendance.

Yet a few months later, in October, Redfield presented the same analysis during a medical conference in California, according to Dr. Craig Hendrix, director of the HIV program in the Air Force. Hendrix was at the conference, “literally trembling in my seat,” he told USA TODAY. “I couldn't believe this was happening again.”

Desperate patients and limited government resources were being funneled into a boondoggle, Hendrix thought. The day he returned from the conference, he filed a formal allegation up the chain of command.

“The data analysis has been sloppy or, possibly, deceptive,” Hendrix wrote to Redfield’s supervisors at the lab. Redfield appeared motivated by the congressional grants, which lent “the appearance of a very gross impropriety,” Hendrix wrote. “We cannot continue to deceive."

Hendrix’s letter led to two military investigations into Redfield’s lab. USA TODAY obtained the testimony and other evidence after the advocacy group Public Citizen filed a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit. The records were first reported by Science Magazine in 1993.

Redfield, Birx and other senior officials in the lab blamed misunderstandings and disgruntled colleagues. “I deny that I have misrepresented the data and that I have oversold the data,” Redfield told investigators.

The military investigators concluded there was no evidence of scientific misconduct.

The Army did, however, find that Redfield’s lab had an inappropriate relationship with a faith-based HIV nonprofit, Americans for a Sound AIDS Policy, which had lobbied for the vaccine therapy.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

The military concluded that the nonprofit’s co-founder, W. Shepherd Smith, had access to the lab and tried to exert influence. Investigators told Redfield to sever the lab’s ties with Smith.

But Redfield did not sever his own ties with the group. He remained a board member of Americans for a Sound AIDS Policy for 15 more years, until March 2018, when he was appointed CDC director, according to USA TODAY’s review of tax filings and ethics disclosures.

Federal contracting data show that Smith’s group, now called Children’s AIDS Fund, and its spinoff organizations in Africa have received $15 million from the federal government — mostly from the CDC — since 2009. Smith told USA TODAY he pushed for Redfield to lead the agency under the George W. Bush administration and placed calls to Congressional staffers in 2018.

Trump picked “a person of deep faith” and “great integrity,” Smith said of Redfield. “He’s done a lot to help people who are suffering.”

As for the military investigation into the vaccine therapy, Smith denied trying to pressure people in Redfield’s lab. “It was much ado about nothing,” he said.

At the time of Redfield’s appointment, Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., warned that Redfield should never have been chosen to lead the CDC. She called out his “pattern of ethically and morally questionable behavior.”

Murray is now pained to see America paying the price.

“If we can’t trust the info coming from the CDC, we will not make good decisions,” she told USA TODAY. “That should scare all of us.”

Brett Murphy and Letitia Stein are reporters on the USA TODAY investigations team. Contact Brett at brett.murphy@usatoday.com or @brettMmurphy and Letitia at lstein@usatoday.com, @LetitiaStein, by phone or Signal at 813-524-0673.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: COVID-19: CDC director buckled to politics, tarnishing agency