Celebrating Eugene Thaw's Legacy

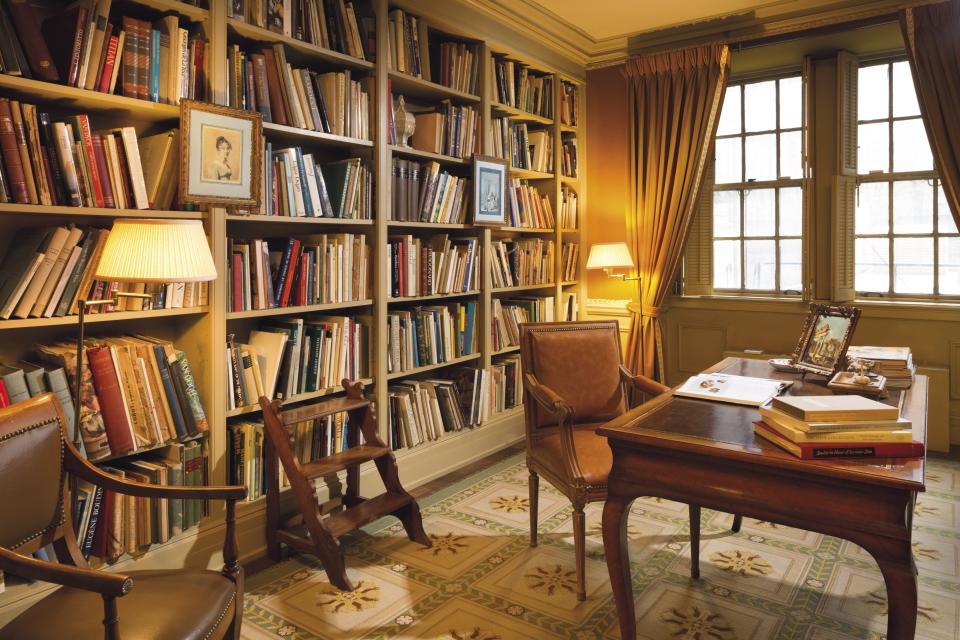

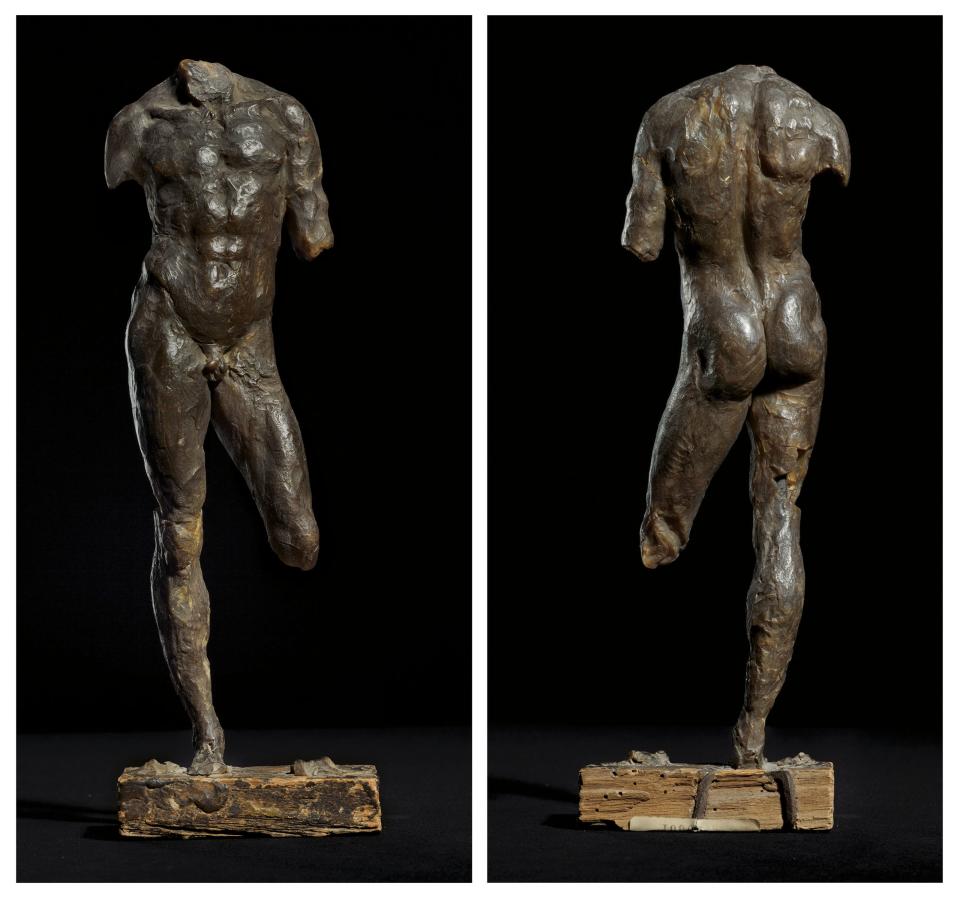

Strolling along Park Avenue in the East 70s last week, I was not surprised when I peered through the ground-floor windows of the maisonette duplex at number 726—a place I had been fortunate to frequent for the past 45 years—and saw that it had been stripped bare of its understatedly elegant furnishings. I knew perfectly well that they had all been consigned to auction (Christie’s, October 30th), along with a plethora of pictures and objects that stand as a testament to an unrivaled eye that spanned an astonishing range of collecting categories: everything from set designer Robert Edmond Jones’s watercolor of Tracy Lord’s Main Line living room for the 1939 Broadway production of The Philadelphia Story purchased from the Katharine Hepburn estate (estimate $2,000 - $3,000), to Fragonard’s expressive oil The Hurdy-Gurdy Player (estimate $400,000 - $600,000). But even though not surprised, I was somehow deeply shocked to see the duplex’s rooms reduced to a welter of blank, staring, un-storied walls.

The man with that nonpareil eye was one—the only and the one—Eugene V. Thaw, who died last January at the age of 90, after a superb career as a private art dealer specializing in European old-master and 19th–century paintings and works on paper. Thaw was a world-class (class being the operative word) collector and an unrelenting philanthropist into the bargain. His could hardly be counted a misspent life: he once ballparked for me that he and his wife, Clare, had donated more than a billion dollars’ worth of art to institutions in New York State alone, including 420 incomparable drawings to the Morgan Library & Museum (making him its foremost benefactor after its eponymous founders, Pierpont Morgan and his son J. P. Morgan Jr.), and almost a thousand superlative specimens of Native American art to the Fenimore Art Museum. Eugene Thaw had lived long enough to achieve art-historical significance himself.

It was here in the shadowy confines of 726 Park that he had customarily received the directors of the greatest museums in America and on the Continent, not to mention clients the likes of Paul Mellon, Charles Wrightsman, and Norton Simon, all of whose collections he unfailingly enhanced. One day in 2009 I received a runic call from Gene: “I’m ringing your bell in half an hour, we’re going to see some lemons.” He was referring, it turned out, to what he considered the greatest still life in the history of art: Francisco de Zurbaran’s Still Life with Lemons, Oranges, and a Rose, from 1633, which he had sold to Norton Simon in 1972 (it’s the star attraction in the latter’s eponymous museum, in Pasadena) and which was at that moment on loan to the Frick.

Over the decades I had seen come and go (either sold or donated) works by masters old (such as Gericault, Daumier, Delacroix, Tiepolo, Rembrandt, and Goya) and newer (such as Degas, Matisse, and Picasso), all of them in the period frames that Gene had perfectly selected himself.

And one mustn’t forget the Jackson Pollock drip painting (its previous owner was MoMa president Mrs. John D. Rockefeller III) that was moved to the foyer after I had been so bold as to ask why it was hanging over a fax machine! (Back story: Gene had befriended Pollock’s widow, Lee Krasner—he called her Lee-Lee—one long-since-vanished summer in East Hampton, and she soon entrusted him with selling some of her remaining Pollocks. In the ‘70s he co-authored the four-volume Jackson Pollock catalogue raisonné—a seven-year scholarly endeavor. And finally, in the fullness of time, he became co-executor of Krasner’s estate and established, serving for several years as its president, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, which makes grants to needy artists.)

Between 2006 and 2010, anointed by him to do so, I conducted a series of interviews with Gene for Architectural Digest that reached both backward and forward in his continuities—some thirteen in all. Taken together, they constitute most of what little there is out there of his ideas about art and, by extension, life. Whenever a new installment appeared, he would receive accolades and fan mail (there was even an anonymous mash note). The low-profile, guarded Gene said to me, with a shy smile, “You’ve made me famous.” And in a way it was true—before this, he was merely legendary! I, for my own part in the chronicling, was roundly attacked at a dinner party by Jackson Pollock’s erstwhile girlfriend Ruth Kligman for “allowing” (!) Gene to quote the poet and art critic Frank O’Hara’s tag for her—the “death car girl”: a nickname earned when she rode shotgun in the blue Oldsmobile convertible coupe that Pollock was driving, drunk, when he lost his head and crashed—or rather, crashed and lost his head, since he was in fact decapitated. (Supposedly, after O’Hara had met his own end under the wheels of a Jeep on a Fire Island beach, Kligman vindictively penned the lines "You called me Death Car Girl/ But look who's dead now.")

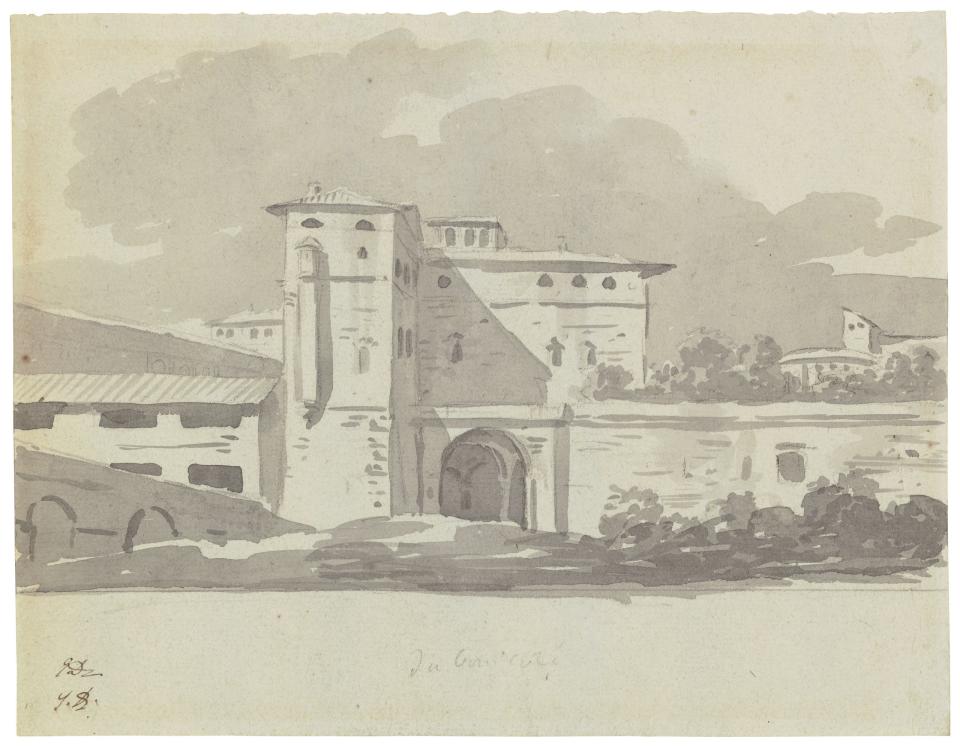

Need I say that to be standing with Eugene Thaw in front of a picture—any picture, anywhere—was to be in a most privileged position. Derivations, attributions, and obscure bibliographical references were all within the easy reach of his phenomenal memory. He had thousands of pictures stored in the museum of his mind and could reel off what was in every corner of any one of them. (The famous eye was apparently not totally infallible, though—on our way back from the memorial service at the Metropolitan Museum for his old friend the renowned art dealer Andre Emmerich in 2007, Gene confessed that Andre’s mother, some sort of dealer herself, had once succeeded in selling him a fake Impressionist picture.) When presented with a genuine work of art, whether for the first or the hundredth time, Gene would become palpably excited. He was enamored of pictures: drawn to them—drawings especially—by romantic feelings (romantic with a capital R as well, since so many of the artists he collected were of that late-18th and early 19th-century Movement). He maintained that he needed to have emotional as well as intellectual access to every work of art he sold or collected.

Gene never actually lived at 726 Park—the maisonette served alternately as his office and the couple’s pied-à-terre. He preferred to commute fifty minutes each way to “Edgehill,” his splendid Stanford White house in Scarborough-on-Hudson that was known locally as “the brick villa.” The Thaws’ Great Dane, Kelly, a dog of the greatest sweetness, had the run of the place, bounding onto the golf course of the Sleepy Hollow Country club that Edgehill abutted; not to be outdone in the dog department, I would arrive for a weekend with my Newfoundland, Ned—an equally large and, sadly, equally short-lived breed. Gene and Clare developed a close relationship with their country neighbor John Cheever, who once told me he liked everything that Gene had: I like Gene’s house, I like Gene’s wife, I like Gene’s dogs, I like Gene’s pictures, and I like Gene’s mind.” Gene for his part greatly admired “Cheever,” which is what he called him, and adored Cheever’s daughter, Susan; and when the time came, he would deliver an affectionate eulogy at the writer’s service in Ossining, following no less than Saul Bellow on the dais.

A few years after I had first met the Thaws, I was providentially the catalyst for one of his celebrated sales. I was a good friend of the decades-younger widow of the photographer Edward Steichen, and somewhat unaccountably Joanna had asked me to recommend a dealer to sell a prized work of art that her husband had given her as a gift. I naturally brought Gene into the picture—or in this case, the sculpture. And what a one it was: Brancusi’s polished-bronze cast of Bird in Space. Steichen had purchased it directly from the sculptor in Paris in 1926, and it arrived in New York escorted by Marcel Duchamp. The U.S. Customs Service, however, refused to acknowledge it as a work of art and to exempt it as such from import taxes; it was classified as a utilitarian object, under the Service’s “Kitchen Utensils and Hospital Supplies” category. Steichen had the bird sprung on bond and then, encouraged by the sculptor and museum founder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney who put her lawyer at his disposal, he filed suit appealing the decision and seeking to recover the import duties he had been made to pay. At the headline-making trial—Brancusi v. United States—the avian avatar sat dormant on the table. Steichen won: the bird soared, leaving in its wake a precedent-setting victory for abstract art. “Bird was its own best witness,” the great photographer recalled. “It was the only clean thing in the courtroom. It shone like a jewel.” How fitting, then, that Gene should sell it to a man named Diamond (a private art dealer and the father of a future Beastie Boy) half a century later.

In the ‘80s, the Thaws sold their Stanford White house to a flamboyantly named Metropolitan Opera singer of my acquaintance, Brenda Boozer, who was married at the time to the comedian Robert Klein (the couple’s life there may not have been a barrel of laughs, but that is another story) and hied themselves to the 800-acre dairy farm, complete with a herd of Black Angus, that they had purchased some years before in Cherry Valley, near Cooperstown, in upstate New York. The animating idea here was that the trip from Manhattan was so major that, once they had finally arrived, they would want to spend long stretches of time there.

By 1987, with many record-setting picture sales under his belt, Gene had become disgusted—his word—with the trophy-hunting and money-grubbing that had come to characterize the art world, and he decided to retire from active dealing. He confided to me that the last straw for him had been when Ronald Lauder, to whom he had sold the 15th-century Flemish artist Dieric Bouts’s masterpiece painting on linen, The Annunciation, sent it back, having been persuaded by a lesser dealer that it was a freshly executed fake. Thaw refunded Lauder’s seven million, then proceeded to turn the picture around in a flash: the Met, where it had been on exhibition, vied for it, but it was the Getty that got it, and it quickly became one of their biggest draws. The very idea that his unimpeachable judgment had been questioned, not only privately but publicly (the story had been picked up by the papers), made Gene, he told me, “physically ill—I felt like I had ingested rat poison.”

Fortunately, the antidote was at hand: he was pleased, and validated, when he was asked to appraise the art in the recently deceased Georgia O’Keeffe’s estate, to which end he and Clare repaired to Santa Fe. Taking the measure of New Mexico and finding it ravishing in all respects, they went on to build a Territorial-style house right in Santa Fe and to acquire a sizable ranch half an hour outside town. Gene would commute when necessary to the Park Avenue maisonette, on the private jet he now co-owned with a local art dealer (the pilot, I recall, had the reassuring name Buck). In no time he and Clare began collecting Native American Art characteristically, Gene had steeped himself in the relevant literature and been in constant consultation with the advisory universe, determined to apply here the same standard of connoisseurship as he had to his manifold other collections). No wonder, then, that within just a handful of years they had managed to amass the finest collection of its kind in a generation. When they donated it—lock, stock, and barrel—to the Fenimore Art Museum in 1991, the institution had to build a wing to accommodate it all. (In preparation for my dedicated interview with Gene on the subject, I made the pilgrimage to Cooperstown to see the collection in situ. I took care to bring my hunting dog along for the ride—seven hours each way!—since his name happened to be Hawkeye, as in The Last of the Mohicans, and the museum happened to be situated on the site of James Fenimore Cooper’s original farmhouse. The coincidence was too good for Gene to resist, and he called the museum to suggest that the dog be welcomed and admitted.)

Gene and Clare became the most persevering philanthropists in all New Mexico (I remember bumping into him in a restaurant in Manhattan when he was deep in conversation with that state’s former governor, Terry Richardson, who was an adviser on some of Gene’s eleemosynary endeavors). In the early ‘90s he had further enriched the foundation that he and Clare had earlier created, the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust, with the 40 million dollars he received from the sale of a single painting he owned, Van Gogh’s 1888 oil Flowering Garden. They were thus able to considerably step up their giving—concentrated in areas related to ecology and animal welfare (they built a five-million-dollar veterinary hospital, God bless them) as well as to the arts. The opera being a particular passion of Gene’s, he was a great patron of the Santa Fe, Glimmerglass, and Metropolitan operas, and one of his favorite drawings was Juan Gris’s subversively comical Cubist Man with Opera Hat (Gene paid a million dollars for it in 2005 to the son of the man he had sold it to for $10,000 thirty years before—“Never sell anything you wouldn’t want to buy back should it ever come on the market again” was one of his mantras).

Gene was personally generous as well—almost to a fault. At one point, I remember, he bought a midtown apartment for the esteemed Metropolitan Museum curator Bill Lieberman; he attended in every way to a cherished godson in London who was dying of a brain tumor; and to ensure his longtime friend Rosamond Bernier a comfortable old age, he put his dealer’s hat back on and brilliantly sold her most valuable surviving picture for her—a Miró.

All through the years Gene remained unwaveringly loyal to Claus von Bulow, whom he had first encountered when they served together on the board of Baron Leon Lambert’s Artemis Art Advisers. “Sunny refused to let him out of her sight for a minute, she wouldn’t let him go to work,” Gene recalled for me. "So I made an office for him upstairs in our apartment, which was okay with Sunny, who liked and trusted me—we had bonded over our love of dogs. The idea was that Claus and I would give freewheeling kind of advice to anyone who wanted to form a collection, and that Claus would mine his social connections in Newport and elsewhere.” Gene went so far as to create a joint corporation, printing stationery and stock certificates. But then: “Claus was coming in every day and Clare was getting fed up: first of all, he is so huge they couldn’t pass on the stairway together, and our privacy began to be affected—he had a steady stream of visitors, people like John Richardson, who he would have meet him in our apartment before going out to lunch. He did manage to find a collection of good modern pictures belonging to some big Newport family. I put up several hundred thousand for the purchase and did all the selling, and Claus as my partner and my introducer to the whole shebang got a big chunk.” Gene testified in Claus’s first trial, a witness to the fact that Claus had substantial assets of his own and was therefore not exactly desperate for Sunny’s money. “I had by then given him so many commissions and also sold some pictures that he owned himself. He told me that he never saw that movie Reversal of Fortune. Which was just as well. Jeremy Irons played him in a sinister kind of way, and whoever did the set design got it absolutely wrong—they had bouquets of gladiolas. Everything was wrong in that way, you know—it was all just an inaccurate and rather unpleasant take on what the Von Bulows’ lives really were.” Gene would go on speaking at least once a week to Claus and seeing him whenever Gene found himself in London.

The Thaws’ base remained New Mexico until 2012, when Clare developed respiratory problems that necessitated their picking up sticks. They reluctantly returned to Cherry Valley to, in effect, finish out their time (and to a smaller, roughly thirty-acre property with a nice enough house, the farm having long since been sold).

Now that Gene was back East for the duration, I got to see a good deal more of him. In his last years he would come into town a couple of times a month for various museum board meetings and would call me for dinner, usually at the last minute, and I would drop everything to meet him. It was always at 6:30, and always at our neighborhood Italian, Sette Mezzo, where he could well have commanded a table in the preferentially seated front room but opted instead for the last table in the back. He would good-naturedly complain about the cost of the car-and-driver from far-off Cherry Valley (“an arm and a leg”) and about the high prices charged by the restaurant, which left me no choice but to order the least expensive item on the menu, the spaghettini pomodoro (an excellent choice, in point of fact, since it also happened to be the most reliable). The last time we were there together, as we were threading our way to the front door, I stopped to introduce him to the chairman of the board of the Metropolitan Museum, who, when he heard Gene’s name, shot to his feet in admiration, if not homage.

Gene’s middle name was Victor, but the battle of old age he did not win. He suffered his share of its ignominies, including the loss of some of his power of locomotion—a state-of-the-art stair lift (“Cost me almost $10,000!” he grumbled) had been installed in the duplex, and when he left the premises he was on a sturdy cane. Names were beginning to escape him, too, and he would become impatient, even angry, with himself. I hastened to point out that they had already begun escaping most people who were thirty years his junior. One time, he couldn’t readily produce the name of a famous long-dead dealer of Van Goghs, while remembering that in German it meant “field of violets.” An hour later it came back to him with a vengeance—“Walter Feilchenfeldt!” he bellowed triumphantly over the phone to me (he never learned to use email).

A few years ago, when a good friend died, I found myself suddenly placed in the position of a latter-day surrogate Maecenas. Out of a large estate, whose charitable disbursements I had been left in control of, well, disbursing, I designated two million dollars to Gene’s beloved Morgan—inspired to do so not only by his own example but by that of another philanthropic nonagenarian longtime friend of mine, Robert M. Pennoyer, who was born in the Morgan Library—or rather, in his grandfather J. P. Morgan’s mansion a stone’s throw from it. When that freestanding 45-room 1850s Anglo-Italianate brownstone came up for sale in 1988, Gene gave the Morgan a substantial sum toward its acquisition and later threw in a ten-million-dollar endowment for a Thaw Conservation Center on its fourth floor (having already endowed at the Morgan a Drawing Institute, a Clare Eddy Thaw Gallery, and a curatorship of drawing and prints).

By now Gene’s verve for living had abated—the shine had gone off virtually everything. He would not be one to cling tenaciously to life, he insisted, adding that he had preemptively made arrangements for his young Corgi, Toby, to be left in the care of the caretaker of the property in Cherry Hill. Gene declared time and again that he was contriving to stay alive only for the exhibition of his drawings scheduled to open at the Morgan in late September 2017, to coincide with his 90th birthday. He immersed himself in every detail of the selection, installation, and overall presentation (he had not been best pleased, I recalled, when the Morgan’s 2002 show of some of his drawings was installed in a gallery across the marbled hall from a show titled “On the Money: Cartoons for The New Yorker”).

When Clare slipped away on June 29th, her 93rd birthday, Gene effectively shut down, willing himself to die. The marriage—fortified by their passionate partnership in collecting (she had been his first assistant, back in the ‘50s, after all)—was the bedrock of both their lives. For sixty-three years they had been a plural being: Gene and Clare. And yet, the show must go on.

Drawn to Greatness: Master Drawings from the Thaw Collection more than lived up to its title, in both quality and diversity. Among the 150 pictures on glorious view were masterworks by Seurat, David, Daumier, Goya, Guardi, di Chirico, Mantegna, Constable, Monet, Chagall, Ingres, Corot, Pissarro, Delacroix, Millet, Matisse, Tiepolo, Romney, Turner, Samuel Palmer, Toulouse-Lautrec, Watteau, Renoir, Rubens, Van Dyck, Fra Bartolommeo, Georgia O’Keeffe, Cezanne, Picasso, Pollock, Miró, Motherwell, Leger, Mondrian, Greuze, Bonnard, Giacometti, David Hockney, Gaugin, Friedrich, Van Gogh (two drawings and three letters with sketches: a far cry from the watercolor reproductions that Gene’s mother, having received them as a premium for being a subscriber to The New York Post, had framed in the house he grew up in, in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan), and Rembrandt (four of them, including the great Chatsworth landscape that Gene purchased in 2000 for almost four million dollars).

The reviews waxed ecstatic—The New York Times, for one, pronounced the exhibition “phenomenal…notable not just for visual charisma but also for chronological breadth, amounting to a veritable history of draftsmanship.” Attendance went through the roof, and the hefty catalogue sold out midway. Gene managed a walk around the show, on a day before it opened, but he was not up to attending the opening. He died at home in Cherry Hill on January 3rd, four days before its closing.

Oscar Levant may have observed, “It’s not what you are, it’s what you don’t become that hurts.” But rest assured that when Eugene V. Thaw went from here to eternity, he had achieved everything he had had it in him to achieve—and more.

STEVEN M. L. ARONSON, a former book editor and publisher, is the author of Hype and the co-author of the Edgar Award-winning Savage Grace and of Avedon: Something Personal. His profiles, interviews, and articles have appeared in such magazines as Vanity Fair, New York, Vogue, Interview, Poetry, and The Nation. He was for many years a contributing writer for Architectural Digest.