Some central Ohio tech workers waiting a lifetime for a green card

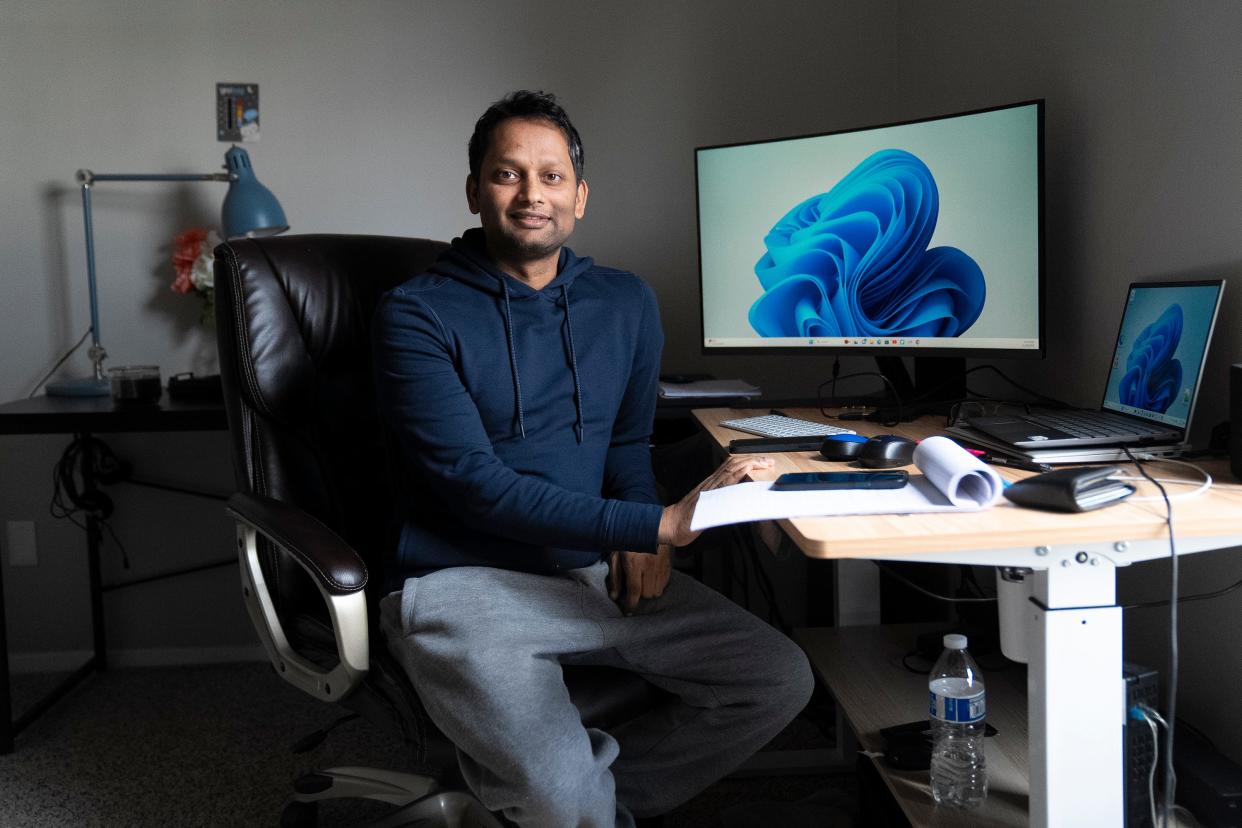

When Shiva Macharla was laid off from his software engineering job last summer, he had 60 days to find a new job — or risk being deported and losing the life he had built over a decade studying, living and working in the U.S.

Macharla, who is Indian and worked for the apparel retailer Express in Columbus, didn’t want to uproot his wife or two young children, or lose the home they had recently purchased in Lewis Center, Delaware County. So, he took the first decent software job offer he got — in Nashville.

“I was in kind of a nervous situation. There's a lot of competition. It’s not that easy to find (a job),” Macharla told The Dispatch.

Now, he drives back to central Ohio from Tennessee every couple weeks to visit his family in their house that he says he can no longer personally enjoy on a regular basis.

Macharla is one of hundreds of thousands of foreign workers in the U.S. on temporary H-1B visas. This class of visa — which is the most common pathway for foreign workers in mathematics, engineering, technology, and medical sciences to get into the United States — requires sponsorship from an employer to gain and maintain legal status.

Around 85,000 H-1B visas are issued nationally every year. At least 16,800 new visas were approved for workers in Ohio over the decade ending in 2022, according to federal government immigration data, though that could be an undercount since it does not include many firms incorporated elsewhere that have employees in Ohio.

As central Ohio gears up to become a technology hub — with Intel, Amazon and others announcing multi-billion-dollar investments in the area in recent years — more and more foreign workers in Greater Columbus are on H-1Bs. The government data show that new H-1B approvals in Central Ohio in 2022 were at their highest in at least 10 years.

For some foreign workers, getting an H-1B is the first step toward gaining permanent residency. But for many others, a green card is an illusory dream. People from countries like India and China can work and pay taxes in the U.S. for a lifetime and never get a green card because of country-based, annual application ceilings, advocates have long complained.

Meanwhile, H-1B holders say their temporary status can invoke feelings of impermanence and anxiety.

“I really liked living in Ohio … with the people in (my) company, I always felt really good. But the visa process was very tedious and did not make me feel stable,” said Pawan Deep Singh, a University of Cincinnati graduate from India.

In 2021, Singh left the U.S. for Canada — which has attracted thousands of H-1B holders with its easier-to-navigate immigration system.

A 134-year wait for a green card

The H-1B visa category, which was created in 1990, aims to fill employment gaps in U.S.-specialty occupations that require at least a bachelor’s degree. In order to obtain an H-1B visa, an employer must petition U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, attesting they will pay the foreigner the equivalent wage of an American worker. Government processing of applications currently takes between 1.5 and 2.5 months, depending on location.

If a worker switches jobs, they must find a new employer that will petition on their behalf. The initial duration of an H-1B visa is three years, which may be extended once, or indefinitely if the worker applies for a green card.

Immigration law provides for approximately 140,000 employment-based green cards to be awarded annually, which is far less than the number of green cards issued to people based on family ties (which constituted about 58% of all green cards issued in 2022). However, no more than 7% of employment-based green cards can go to any one country per year — creating a backlog of 1.8 million applications. Indian workers − who have the longest backlog − can expect to wait for 134 years for permanent residency, according to a recent analysis by The Cato Institute.

‘Like having a gun to the back of your head'

Joseph Hopkinson, a Canadian who worked for several central Ohio tech companies before returning to Canada a few years ago, described the specter of layoffs while on a temporary visa as “like having a gun to the back of your head.”

“(If) my employer decides to fire me, I have (60) days to find another job in my field that will pass scrutiny to maintain my H-1B status …That’s the craziest thing ever,” Hopkinson said by phone from Toronto.

Nonimmigrant visas can also create complications for those who wish to travel.

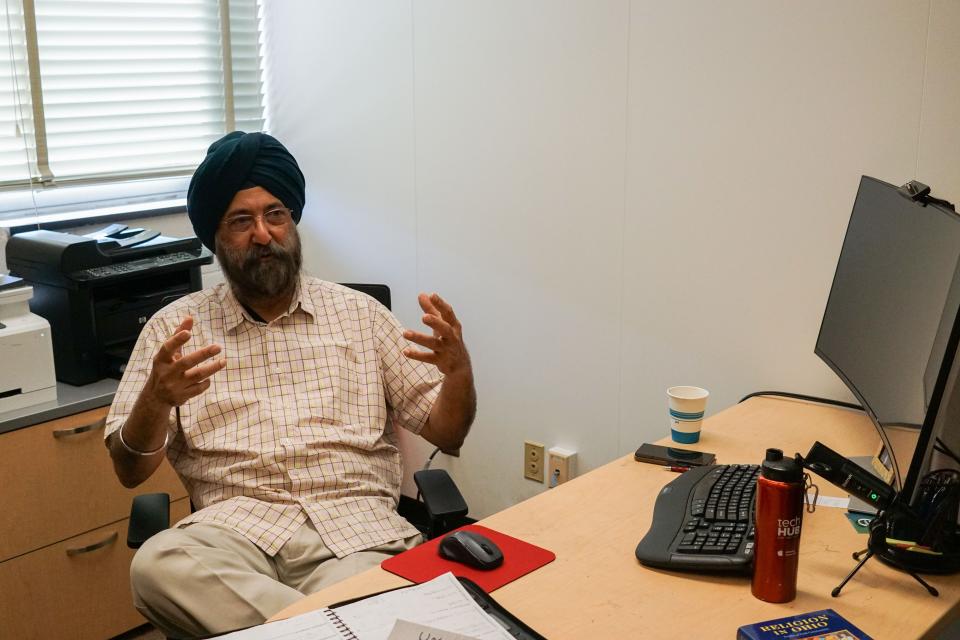

Tarunjit Butalia, a civil engineering professor at Ohio State University, said a former student, a Bangladeshi, was recently in the process of getting his H-1B when the student’s father died. Going home for the funeral would have meant sacrificing his H-1B application, so he chose to forgo it.

“I just can't imagine being in such a situation,” Butalia said.

Shantanu Prakash, an Indian software engineer who has worked for a consulting company in Columbus for seven years, said his visa’s temporary status has made it hard to lay down local roots.

“I wanted to consider Columbus as my home but being on H-1B … it's uncertain. I don't know if there will be a change in government or some policies … and I (could) have to go back to India,” he said.

Canada’s alternative program

Amid major American tech-sector layoffs this year, Canada launched a program to attract tech talent by offering open work permits to H-1B holders in July. The program quickly reached its ceiling of 10,000 applicants; at least 6,000 H-1B holders in the U.S. have since moved to Canada.

Rather than requiring a petition from an employer like an H-1B, many Canadian work permits are ‘open’ — that is, granted on a points-based system and allowing workers to change jobs easily.

Singh, the University of Cincinnati graduate, said he moved to Canada after an encounter with Customs and Border Patrol at San Francisco International Airport in March 2021 left him feeling distinctly unwelcome.

He said officers detained him for several hours, questioning him about his visa status. At the time, he was working legally on a student visa under a provision known as "curricular practical training," he said.

“I thought those officers … were really racist towards me, they tried to interrogate me as if I'm like a criminal. They said, ‘You come from a village and the whole village pays for you, and then you start bringing people from your village.’… It triggered me,” Singh said.

A Customs and Border Patrol spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment about the allegation.

Singh said the Canadian system feels more welcoming, even if Canadian tech jobs usually pay less than American ones.

Recently, he returned from a trip to India.

“You know how the Canadian immigration officer greeted me? He said, ‘Welcome back home,’” Singh recounted.

Prakash, the software engineer, said he doesn’t want to leave his job in Columbus anytime soon.

His advice to other Indians about applying for an H-1B?

“There is a trade off,” he said. “Definitely, we have a great opportunity here — you can earn good money and have a good life, but also there is that uncertainty. You don't know how long you're going to be here.”

More: As central Ohio’s tech industry grows, high-skilled immigrants may be needed to fill jobs

Peter Gill covers immigration, New American communities and religion for the Dispatch in partnership with Report for America. You can support work like his with a tax-deductible donation to Report for America at:bit.ly/3fNsGaZ.

pgill@dispatch.com

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Some central Ohio tech workers waiting a lifetime for a green card