The Century of Black Women Activists Who Paved the Way for Kamala Harris

Joe Biden’s choice of Sen. Kamala Harris as his running mate is rightly heralded as a historic moment for Black women. For the first time, a Black woman is the presumptive nominee of a major party ticket. This moment comes 100 years after women gained the right to vote with the passage and ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920 and 55 years after the Voting Rights Act guaranteed the ability of Black people to exercise their franchise.

Harris’ rise reflects her own long list of qualifications—district attorney of San Francisco; first African American and first woman attorney general of California; second African American woman and first South Asian American in the U.S. Senate. But her rise—hastened in part by this summer’s national protests that likely factored into Biden’s decision—also has deep historical roots in the extensive record of Black women’s political activism in the U.S. For example, Harris’ nomination comes over six decades after Charlotta Bass made history as the first Black woman to run as a vice presidential candidate in 1952. Joining the Progressive Party’s ticket, Bass championed social and economic justice. Black women have always functioned at the intersections of gender, race, class, sexuality and ability. Likewise, Black women have historically fought on multiple fronts from abolitionism and suffrage to equal rights and civil rights.

Even before enslavement was abolished, Black women played vital roles in social justice movements. Enslaved women led labor strikes that shut down plantation operations for weeks, went to court and petitioned for their freedom and won, and dressed as men and went to war in the name of liberty. Abolitionists like Sojourner Truth, Henrietta Purvis, Harriet Forten Purvis and Sarah Parker Remond were avowed suffragists who passionately advocated women’s right to vote. After the Civil War, masses of Black women organized suffrage campaigns throughout the country in cities as wide-ranging as Tuskegee, Alabama; St. Louis; Los Angeles; Boston; New York and Charleston, South Carolina.

On Wednesday, Harris will address her party’s virtual convention from Wilmington, Delaware, (Biden’s hometown) and formally accept a nomination that enshrines her place in history. But in ascending to this point, Harris is also heir to a deep and underappreciated legacy in American political life: the Black women who, over the past century, fought to claim their rightful share of American political power, and the Black women voters who have been key to holding those gains. Their history also offers a glimpse of the kind of pushback Harris will face (and has already faced) from people who still are not comfortable seeing Black women in positions of power. This was something former first lady Michelle Obama addressed in her remarks on opening night of the Democratic National Convention: “Now, I understand that my message won’t be heard by some people. We live in a nation that is deeply divided, and I am a Black woman speaking at the Democratic Convention.” She recognized that her presence as a woman of color shapes how some people view her. But Black women persist.

As early as 1918, Alice Sampson Presto, who had worked as a secretary for the Seattle branch of the NAACP, was the first Black woman to run for a seat in a state legislature. Even then, Presto had a progressive and arguably feminist platform. She campaigned on equal pay regardless of gender; she advocated a cost-of-living increase in widows’ pensions; and she believed that taxpayers’ children should not have to pay tuition at state institutions. Though Presto lost, she broke new ground in terms of Black women’s engagement with the electoral process. And those efforts were met with fierce resistance.

After 1920, Black women redoubled their efforts with renewed vigor. Just as white supremacists worked tirelessly to suppress the Black vote, Black women worked equally as hard to make sure that their votes counted. Black women organized voter registration drives wherever they could, including states such as California, New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Kansas and Colorado. Still, in large parts of the South, white supremacists used violence, racial tyranny and things like poll taxes to disenfranchise masses of Black voters. In response to the conditions, Black women, through the National Association of Colored Women and the NAACP, provided information and testimony in 1920, to support legislation proposed by Massachusetts Representative George Holden Tinkham. The Tinkham bill aimed to expose the systematic repression of Black voters in the South by forcing states to use the actual number of votes cast rather than population as the basis of congressional reapportionment. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the bill was defeated, but this did not stop Black women from continuing to organize against voter suppression.

Soon after, Black women formed the National League of Republican Colored Women (NLRCW), with the energized motto, “We are in politics to stay and we shall be a stay in politics.” Renowned Black educator Nannie Helen Burroughs served as president, and prominent Black activist Mary Church Terrell was treasurer. Together, they informed voters about candidates and also made the rounds to reassure the more devout within their ranks that casting a ballot did not interfere with Christian values. Burroughs in particular toured with candidates, visited Black churches and played a vital role in fundraising for upcoming elections. The NLRCW tried to use Black women’s concentration in the Republican Party (then still regarded as the party of Lincoln) as a voting bloc, but they would eventually grow frustrated with the general lack of acknowledgment for their party loyalty. Increasingly, Black women moved away from the Republican Party, which remained inactive on civil rights.

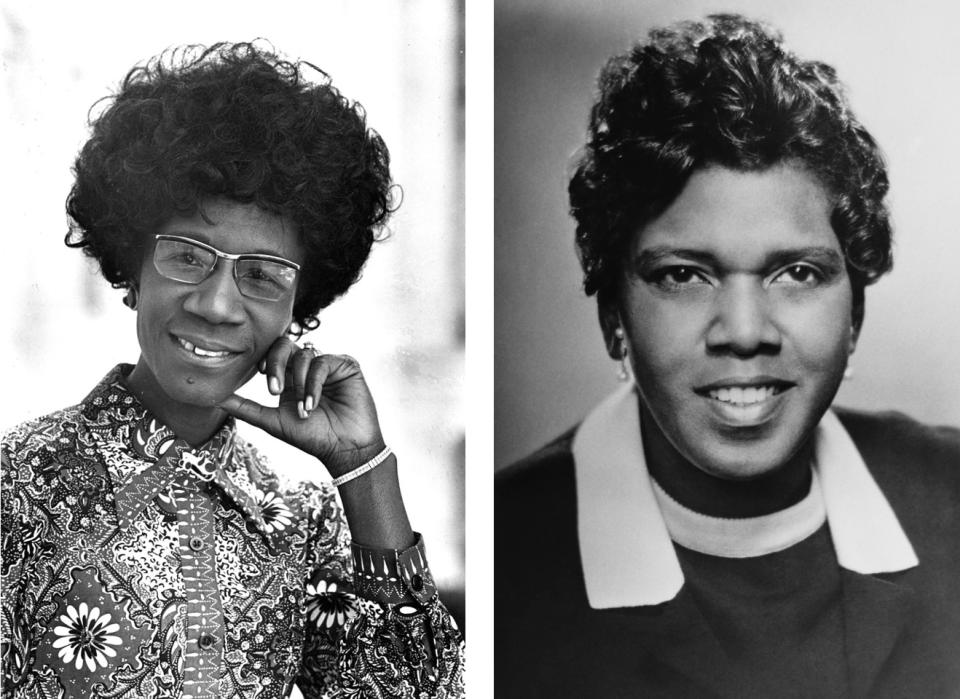

By the 1930s, the NLRCW had disbanded and more and more Black voters gravitated toward the Democratic Party. It also helped that first lady Eleanor Roosevelt was sympathetic toward civil rights and had a rapport with Mary McLeod Bethune, who, among her many accomplishments established the National Council of Negro Women in 1935. Bethune later became director of the Negro Division of the National Youth Administration, effectively becoming the first Black woman to lead a federal agency. Moreover, where Alice Presto failed, Shirley Chisholm succeeded in not only becoming the first Black woman elected to Congress in the late '60s, but also, she was the first Black woman to run for president in 1972.

Black women political activists have made significant policy interventions to address the needs of the poor and working class, and otherwise disadvantaged. For example, in 1966, Barbara Jordan became the first Black woman elected to the House of Representatives from the Deep South where she called the nation back to its principles at every opportunity. Like the women before her, she was always concerned about the poor, thus it is no surprise that she used her role as a Texas state legislator to help pass the state’s minimum wage law and played a vital role in erecting the Texas Fair Employment Commission. She also spoke powerfully at the opening of President Richard Nixon’s impeachment hearing when she declared: “I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution.” Like Jordan’s commanding remarks nearly 50 years ago, Kamala Harris also participated in an impeachment hearing of a sitting president. A week before that hearing, Harris made the following remarks:

“I speak to you today, fully aware that I stand on the shoulders of those who came before me in our nation’s ongoing fight for equality. I speak because I was raised by people who spent most of their lives demanding justice in the face of racism, misogyny, bigotry and inequality. I speak because I have dedicated my entire career to upholding the rule of law and bringing integrity to our system of justice.”

Harris began by recognizing the activists before her. But as we learned in earlier movements, everyday Black women also facilitate important changes. Women like Sandra Bundy, a corrections worker who in 1977 laid the legal framework for combating workplace sexual harassment when she successfully sued the Washington, D.C., Department of Corrections. Although she initially lost the case, Bundy appealed and remained in court for five years, taking the case all the way to the Supreme Court where she was victorious. A single working mother, Bundy had been routinely harassed and propositioned as an employee. Her federal suit helped establish sexual harassment as an unacceptable form of sex discrimination and paved the way for Anita Hill decades later, and women in the #MeToo movement today.

Yet even as Black women have been at the forefront of political and social activism, many found themselves on the receiving end of harsh criticism from inside and outside of the Black community. Chisholm was marginalized by the media, her campaign materials were routinely vandalized, she faced criticism for supposedly taking power from Black men and she was nearly attacked by a knife-wielding maniac. Navigating racism and restrictive gender codes could be perilous terrain indeed, a difficulty that has clearly endured. Today, as we celebrate the centennial of women’s suffrage, we witness the ways female elected officials such as Harris, and Reps. Karen Bass, Val Demings, Maxine Waters and Barbara Lee exist on a historical continuum with their Black women forerunners. They too have received harsh criticism, evidence of just how little has changed.

Black women elected officials continue to be denigrated, not for their political positions or legislative actions, but rather for supposedly being “too ambitious” and formidable or angry. They are also regularly subject to racist insults about their physical appearance. Moreover, in spite of Black women’s historic and ongoing robust voter turnout—largely in support of the Democratic Party—Black women as a group remain among the least served by the electoral process. The record numbers of Black women in political office is heartening, but clearly, like their predecessors, Black women politicians, activists and everyday citizens must remain vigilant in their efforts to beat back voter suppression, to stop police brutality and to seek justice is cases like that of Breonna Taylor, as well as to continue to fight for quality health care, housing and education for all Black women.