Ceres: The Smallest and Closest Dwarf Planet

Ceres is a dwarf planet, the only one located in the inner reaches of the solar system; the rest lie at the outer edges, in the Kuiper Belt. While it is the smallest of the known dwarf planets, it is the largest object in the asteroid belt.

Unlike other rocky bodies in the asteroid belt, Ceres is an oblate spheroid, rounded with a rotational bulge around its equator. Scientists think Ceres may have an ocean and possibly an atmosphere. The recent arrival of a probe has unlocked some of the dwarf planet's secrets, but others remain hidden. [See more photos of the dwarf planet Ceres]

Bright spots & lonely mountains

On March 6, 2015, NASA's Dawn spacecraft became the first probe to orbit two bodies in the solar system. After leaving the asteroid Vesta, Dawn traveled to Ceres, an icy world that has tantalized scientists for years. While most asteroids are made of rock, Ceres revealed hints that it could contain water on its surface since 1991, though those hints remained unconfirmed for more than 20 years.

Most of the surface is a dull gray. Spectral observations from Ceres have revealed the presence of a form of graphite known as graphitized carbon.

"It hasn't evolved to proper graphite," Amanda Hendrix, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona, told Space.com. But it's close.

As Dawn drew closer to the giant asteroid, a bright spot on its surface grew clearer. After observing Ceres, 130 similar spots of varying brightness were found on the planet. The surface of Ceres is generally as reflective as freshly poured asphalt, while the spots ranged from the dull sheen of concrete to the startling brightness of ice floating on Earth's oceans. The brightest region lies in the 56-mile-wide (90 kilometers) Occator Crater, which contains the most famous collections of shining spots on the surface of Ceres.

Early speculation regarding the spots included the possibility of ice volcanoes on the dwarf planet. However, only a single "lonely mountain" rises from the surface. The pyramid-shaped mountain rises to an altitude of 21,120 feet (6,437 meters). The 4-mile high mountain stands solitary, with no evidence of volcanic or other geologic activity to suggest its puzzling origin.

Although a study of the spots originally found signatures of hydrated magnesium sulfates, the same material that makes up Epsom salt back on Earth, further examination revealed chemical signatures of sodium carbonate. Formed from carbon, on Earth the material is often left behind as water evaporates, suggesting that the salts formed in the watery conditions beneath the crust. Most of the bright regions are associated with craters, suggesting that their formation could be related to impacts. These findings tie into earlier understanding of the formation of the dwarf planet.

Ceres' features are named for agricultural spirits and gods, and were approved by the International Astronomical Union in 2015. Ceres itself was named for the Roman goddess of corn and harvests.

A once-wet world

Ceres may look dry and gray, but it probably held a liquid ocean in its past. Dawn used the dwarf planet's own bulk to map its gravity field. Combined with observations of the icy surfaces, the observations reveal traces of an ocean in the crust, with signs of a muddy mantle below the surface.

Ceres has a density of 2.09 grams per cubic centimeter, leading scientists to conclude approximately a quarter of its weight is water. This would give the dwarf planet more fresh water than Earth contains. By comparison, Earth has a density of 5.52 grams per cubic centimeter. Before Dawn visited the dwarf planet, scientists already suspected that it could hide a liquid or frozen ocean; the visiting satellite helped dive into the secrets lurking beneath the planet's surface.

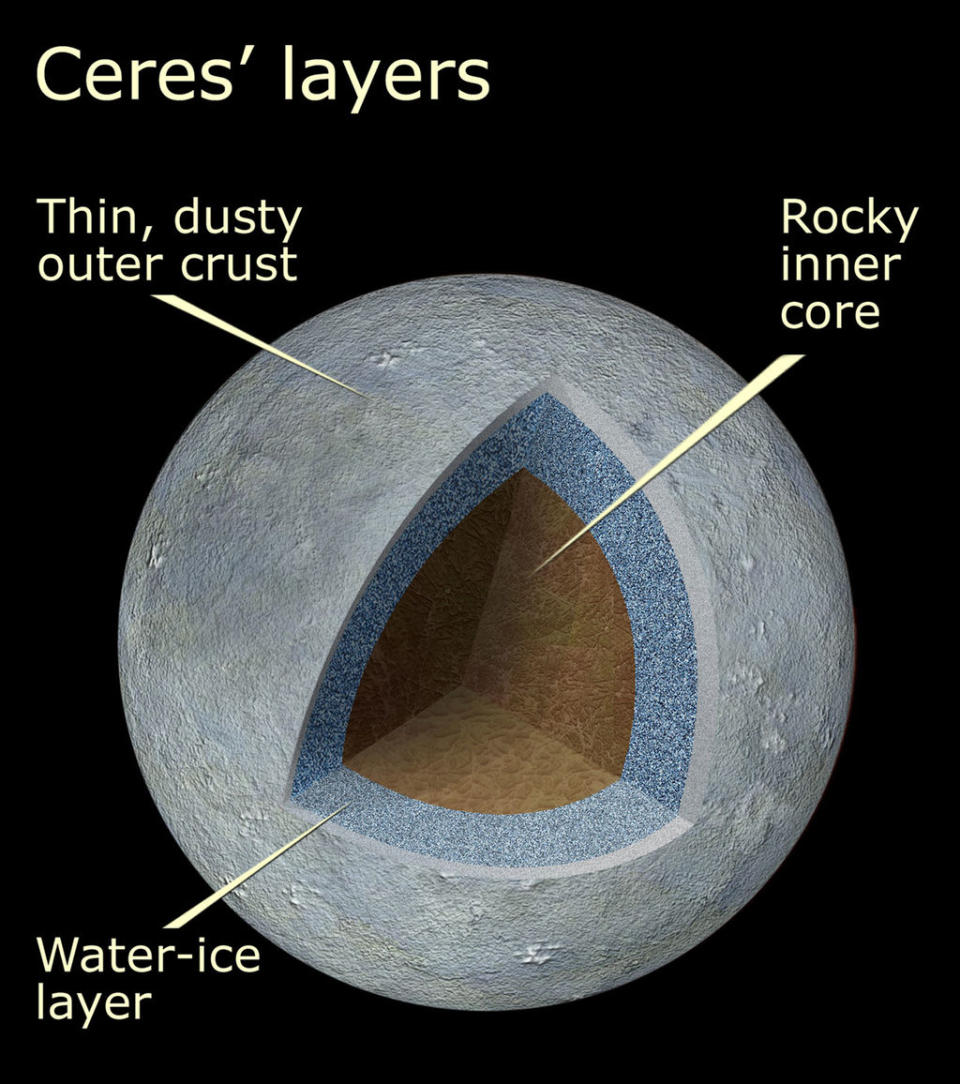

Scientists think that water-ice serves as the mantle of the dwarf planet. The thin, dusty crust is thought to be composed of rock, while a rocky inner core lies at the center. Spectral observations of Ceres from Earth reveal that the surface contains iron-rich clays. Signs of carbonates have similarly been found, making Ceres one of the only bodies in the solar system known to contain these minerals, the other two being Earth and Mars. Formed by a process that involves heat and water, carbonates are considered good potential indicators of habitability. [The Search for Life on Mars (A Photo Timeline)

"That was something we had not expected," Chris Russell, Dawn's principal investigator and planetary scientist at University of California, Los Angeles, told Space.com in 2016. "The carbonates are a very strong indication of the processes now that we believe took place in the interior, that makes it more Earthlike, when it can alter the chemistry inside."

Salts would lower the freezing temperature of water hidden within the crust, keeping it from freezing as quickly as pure water might do.

When large bodies crash into Ceres, they may scoop out a region of the crust, cutting into the icy mantle beneath to leave the ice closer to surface. When sunlight heats the outer layer, the ice could go from solid to gas through a process known as sublimation.

In 2014, the European Space Agency's Herschel Space Observatory detected plumes of water vapor escaping from the dwarf planet at a rate of 13 lbs. (6 kilograms) per second.

"This is the first clear-cut detection of water on Ceres and in the asteroid belt in general," Michael Küppers of the European Space Agency, Villanueva de la Cañada, Spain, told Space.com in 2014. Küppers led the study of the vapor that appeared in Nature.

But not all of the water is hidden beneath the surface. Dawn has revealed growing patches of ice and minerals related to liquid water on the tiny world.

Andrea Raponi, a researcher at the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF), found a growing patch of ice on the floor of Juling Crater, scraped out near the mid-latitudes. A second team, led by Filippo Giacomo Carrozzo, also of INAF, revealed changes in the soil that they suspect are tied to carbonates.

"The same process can be at work in the crater floor of Juling, providing a replenishment of water under the soil that sublimates and in part condenses on the cold wall," Raponi told Space.com.

"The two works show that water is currently available on the surface of Ceres and produces geological and mineralogical changes on its surface," he said.

These patches may change as the planet tilts over thousands of years. Ceres' tilt relative to its orbit changes from 2 degrees to about 20 degrees over the course of 24,500 years, a relatively short time astronomically speaking. This can cause dramatic swings in which craters can continue to hide water over long periods of time. Right now, while Ceres' tilt is near its minimum, large swaths of land around the poles don't receive direct sunlight. But 14,000 years ago, when Ceres was at its maximum tilt, those regions shrank, leaving only a handful of areas where ice could continue to hide throughout the shift.

"The idea that ice could survive on Ceres for long periods of time is important as we continue to reconstruct the dwarf planet's geological history, including whether it has been giving off water vapor," said study co-author and Dawn deputy principal investigator Carol Raymond, also of JPL, in a statement.

Dawn also discovered organic-rich areas on the surface and determined that they were most likely native to the dwarf planet. Data from the spacecraft suggest that the organic materials most likely were delivered to the surface from the dwarf planet's interior.

"This discovery of a locally high concentration of organics is intriguing, with broad implications for the astrobiology community," said Dr. Simone Marchi, a senior research scientist at Southwest Research Institute, said in a statement. "Ceres has evidence of ammonia-bearing hydrated minerals, water ice, carbonates, salts, and now organic materials. With this new finding Dawn has shown that Ceres contains key ingredients for life."

History & discovery

Astronomers in the late 18th century mathematically predicted the presence of a planet between Mars and Jupiter, eagerly turning their telescopes to the region in search of the missing body. On Jan. 1, 1801, Sicilian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi discovered what was then considered a planet, naming it Ceres for the Roman goddess.

Within a decade, four new objects were discovered in the same region, all also considered planets. Nearly 50 years passed before more, smaller bodies were found scattered between Mars and Jupiter — the components of the asteroid belt — and Ceres was demoted to the status of an asteroid.

In 2006, Ceres was promoted to the status of a dwarf planet; it did not reach full planetary status because it failed to gravitationally clear its neighborhood of debris, though it often retains its classification as an asteroid, as well. [Infographic: Dwarf Planets in the Solar System]

The largest object in the asteroid belt, Ceres makes up nearly a third of its mass. Even so, it remains the smallest known dwarf planet, only 590 miles (950 km) across — roughly the size of Texas. A day on Ceres lasts a little over 9 Earth-hours, while it takes 4.6 Earth-years to travel around the sun.

The close proximity and low mass of Ceres have led some scientists to suggest that it could serve as a potential site for manned landings and a launching point for manned deep space missions.

The source of Earth's water?

Unlike most of the asteroid belt, Ceres contains a significant amount of ice. This could mean similar worlds in the early solar system could have been responsible for bringing water to Earth.

Under current solar system models, Earth would have formed primarily rocky. Any water it held on its surface would have been vaporized when a large protoplanet collided with it to form the moon. For a long time, scientists thought that comets might have delivered water to the reformed Earth as they collided with its surface. However, comet-studying probes have shown that the icy rocks don't contain the right kind of water for their siblings to be responsible for those deliveries. New studies have turned to objects known as main belt asteroids, rock and icy neighbors of Ceres.

"One quarter of the mass of Ceres is water, and three quarters is rock," Russell told Space.com in 2015.

"If we had just a few Ceres-type bodies colliding with the Earth, we can explain where the water came from."

Additional resources

Follow Nola Taylor Redd at @NolaTRedd, Facebook, or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+.