Champions League final: Why, for Liverpool, Trent Alexander-Arnold is so much more than just a footballer

On a piece of wasteland in Toxteth, six lads are playing football – a game of three on three. Their backgrounds reflect the diversity of the area: Caribbean, west African, east African, subcontinent Asian. Only one wears a football shirt but the shirt is this season’s replica and it has a name and number on the back. Alexander-Arnold, 66, it reads.

“He’s boss,” the kid with the shirt says. “I want to play like him.” And with that, he spots an opportunity – a bit like Alexander-Arnold’s corner against Barcelona: the goal is unguarded and he sprays a shot which flies straight in. Another of the lads announces himself as an Evertonian. It also turns out Manchester City have reached into this part of the north west too. But the others prefer Liverpool. It helps that Mohamed Salah is Muslim. As locals, though, Alexander-Arnold is the one they like the most: “He’s boss ‘im,” another lad repeats. “Really boss.”

A few roads back on Upper Parliament Street, Liverpool flags are already hanging from flat balconies. It is twelve days before the Champions League final but the city is already preparing. You can see flags everywhere. Cars, homes, office blocks – even the control tower from John Lennon Airport.

It is not a modern phenomenon because this has always happened whenever one of Liverpool’s teams has reached a cup final – it really always has, ever since the 1960s when Liverpool won the FA Cup for the first time by beating Leeds United in extra time before Everton kept the trophy on Merseyside the following year when they were victorious over Sheffield Wednesday.

Back then there were old men and old ladies wearing rosettes and children too young to appreciate what was happening wearing them too. There was bunting and street parties. This was before the game had kicked off with the possibility of disappointment to follow.

There was a confidence from the lads interested in Liverpool playing that disappointment would not be a feature this time because, “Liverpool know more this year about cup finals than they did last year.” You might not expect youngsters – no more than 15 – to mix optimism with pragmatism when it comes to football but in Liverpool they are, even though attending matches is out of the question because of cost and availability.

Instead, they inhale the club from a distance. They see Alexander-Arnold and it gives them hope. This season, he became the first black or mixed-heritage footballer from the city to play more than 50 first team games for the club in its entire history. When he reached game number 50 in a 3-1 win at Southampton where he created Liverpool’s equalising goal, the landmark was recognised on the club’s website through the prism of Premier League games only. He became the fifth youngest since 1992, only behind – in ascending order – Michael Owen, Raheem Sterling, Robbie Fowler and Steven Gerrard.

There was barely a mention that he had gone somewhere no-one else had been before – that perhaps this changes the possibilities for others hoping to follow the same path. Howard Gayle, like the kids on the wasteland, had been born in Toxteth – or the Liverpool 8 area of Toxteth, which is a much bigger district than many inside the city even realise.

Only Upper Parliament Street separates Liverpool 8 from the roads that lead to Hardman Street and the city centre, a five to ten-minute walk down the hill. There had once been a buzz there, back before 1981 when Granby Street was filled with shops which reflected the needs of all the different people that spilled into the space, largely from commonwealth countries via Liverpool’s docks.

By ’81, with unemployment in Liverpool under Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government higher than anywhere else in the country and tensions with the police boiling, riots – or as people who fought called it, ‘an uprising’ altered Toxteth’s perception and though much has been done by residents to help Liverpool 8 to recover, for those who don’t know about the regeneration it remains the bogeyman of inner city boroughs.

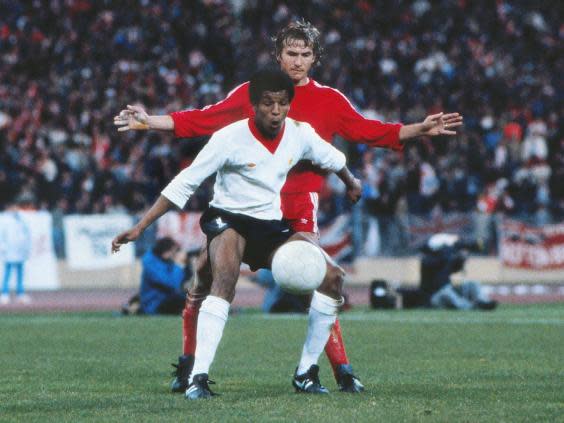

Gayle would leave Liverpool having played just five games. He was contracted to the club during its most successful period and so, the task in front of him was enormous. Ian Rush became the club’s all-time leading scorer but just a few months before the summer of '81, Bob Paisley had preferred Gayle to Rush when Liverpool went to Munich and reached the semi-final of the European Cup. The story about Gayle on that night is well known – introduced as a substitute, he was later substituted because Paisley believed he was on the verge of getting sent off.

Paisley later asked him to move out of Toxteth, which he eventually complied with by buying a house in nearby Mossley Hill. He had challenged racism both from inside the club and out and this contributed towards Paisley wondering whether Gayle was able to keep his cool when it mattered. Liverpool had a decent track record in signing local black players as juniors and apprentices from about 1972 - Maxi Branch, Steve Joel, Leroy Stephens, Lawrence Iro, Steve Skeete, Danny Atwere and Gayle amongst them. But the trail went cold after ‘81.

Other Granby-based black players became professionals in the 1980s, but not with Liverpool and Gayle wondered whether the club’s experiences with him and then the impact of the Riots could have fostered a negative viewpoint or even a new policy.

Hyder Jawad, a journalist and author who has researched the matter, could not find evidence of any local black players at Liverpool between Gayle’s departure and John Barnes’ arrival in 1987. After Barnes, Tony Warner would not arrive until 1992 and like Gayle he came from the south end of the city, only he was born in Lee Park before growing up in the middle-class area of Childwall from the age of 10. He supported Everton and his hero was Neville Southall. His path was unusual.

Aged 18, Warner was still playing for his school team and representing Merseyside, winning the National Cup. Yet he had no serious aspirations of becoming a football player. He started working at an accountancy firm for eighteen months after leaving school. He played for the Rob Roy Sunday League team out of Sefton Park when he received a cold call from Steve Heighway asking him to come to Melwood.

He recognised Robbie Fowler because he’d played against him before. Warner did well enough to be asked back. He became an over-age player in the B team, competing in the Lancashire League on a Saturday before waking up on a Sunday morning and going down for the Rob Roy.

“The contrast in the games was massive,” he told The Independent last week. “You’d be facing technically talented footballers on a Saturday but rough and ready customers on a Sunday who didn’t care if you were still a teenager – anything and everything could happen. You’d try and catch a cross and a centre forward would come flying in with his elbows like Nat Lofthouse.”

Warner progressed into the first team environment where he made 120 appearances, but only on the substitute bench. When asked to picture what it was like at Melwood in the mid-1990s, his memories drifted back towards John Barnes. Warner could remember throwing the ball straight to him only to find out that Barnes had acted as a decoy and had tried to make space on the left wing for Warner to exploit. “He was ahead of everyone else,” said Warner, who also shared a dressing room with another black player in Michael Thomas, as well as David James, the goalkeeper in front of him. Though he ultimately played fewer games for Liverpool than Gayle, he felt at home at Melwood but recognised this was helped by the presence of senior black footballers who held the respect of everyone because of their abilities and achievements.

While Victor Anichebe, who was born in Lagos but grew up in Crosby, would play 131 league games for Everton, Jon Otsemobor (just four league games in 2003/04) and Lee Peltier (no league appearances) were the only locally raised black or mixed heritage players to have played first team football for Liverpool between Warner’s departure in 1999 and Alexander-Arnold’s debut seventeen years later.

Alexander-Arnold was raised in West Derby near Liverpool’s Melwood training ground. Though only Muirhead Avenue separates the area from Norris Green, where Gayle spent the bulk of his early and mid-teens and was the only black face in a low-achieving comprehensive school, Alexander-Arnold – like Anichebe – was educated in the wealthier Crosby before Liverpool recommended he went to Rainhill. For Gayle, his experiences at school had a long-lasting impact, contributing towards the self-worth issues which have followed him throughout his life.

He lives in a flat in Aigburth now but still teaches in Toxteth where he runs coaching sessions which keeps kids like those on the wasteland engaged. His own visibility in the area reminds aspiring young footballers that there's a chance of a career in the game. "Seeing Trent do his stuff," he told me in March, before Liverpool won in Munich, setting them on the road to another European final, "there can be no greater inspiration."