'We have to change the whole system': Experts sound off on how to end police code of silence

Legendary police whistleblower Francesco Serpico uses numbers when he talks about the state of policing in America.

Of all police officers, he estimates that 10% are honest, he told USA TODAY in a recent interview.

Another 10% are crooked, Serpico said.

“And the other 80%,” he added, "are officers who wish they could be more honest.”

Serpico’s breakdown represents what he and many others call the crippling effects of the code of silence in law enforcement. They say the system of secrecy and retaliation is still as alive today as it was a half-century ago, when Serpico’s fellow New York City police officers allegedly refused to back him up and left him to die from a gunshot to the face as retribution for exposing corruption in that department.

Help USA TODAY investigate law enforcement’s code of silence

USA TODAY is documenting how law enforcement agencies around the country threaten and retaliate against internal whistleblowers who expose misconduct by their fellow officers. If you have a story about that or know someone who does, we want to hear from you.

USA TODAY reporters spent a year reviewing cases from the past decade of police officers who made misconduct claims against their coworkers. Reporters found an unofficial but structured pattern of retaliation that played out in the same ways in departments large and small across the country.

Most officers who spoke out said they were threatened, demoted or fired. Some received death threats or were charged with crimes. And when the officers sought help from the courts, prosecutors, and other agencies, USA TODAY found, they were forced to fight alone against a system designed to silence police whistleblowers.

With a deeper look into cases like the death of Eric Lurry in Joliet, Illinois, the firing of Moses Black in Gonzales, Louisiana, and the murder of Jo'Anna Bird on Long Island, New York, the newspaper uncovered the wide-reaching effects of both whistleblower retaliation in police brutality cases and years of efforts to hide misconduct from the public.

USA TODAY’s revelations about how the blue wall works shatter the myth that the problems in law enforcement are limited to “a few rotten apples,” according to experts like DeLacy Davis, founder and executive director of Black Cops Against Police Brutality. Davis says the newspaper's findings prove the system is part of an intentional effort that ultimately promotes the oppression of the nation's most marginalized groups.

“When you go to McDonald’s in California and order a Big Mac, and you go order that same Big Mac on the east coast, or in the deep south, does it taste any different?” Davis asked. “This is a franchise, this is how it was designed to work. So we can’t change it one place at a time. We have to change the whole system.”

USA TODAY reporters interviewed dozens of law enforcement officers, attorneys, experts, activists and others to get their solutions to the pervasive problem. Below are some of their thoughts, which were lightly edited for clarity in some cases:

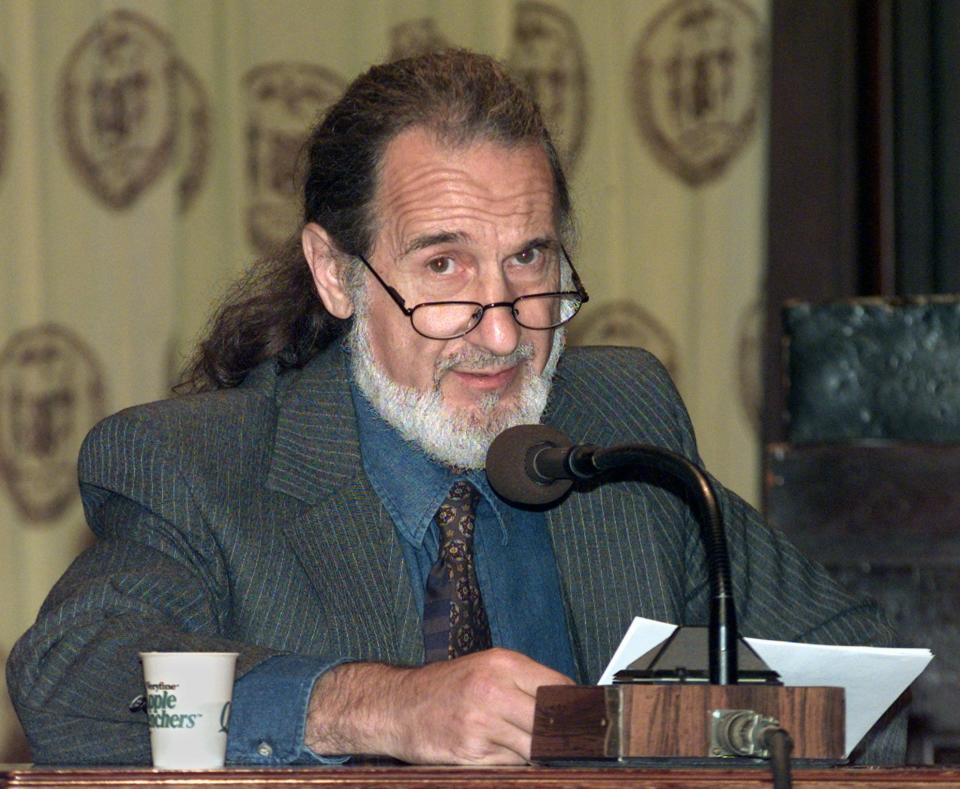

Francesco Serpico

Retired NYPD detective who exposed widespread corruption

It was 50 years ago this month that Serpico testified in December 1971 before the Knapp Commission, a five-member panel assembled to investigate corruption within the NYPD in the wake of revelations Serpico and another officer made to the New York Times. Now long retired from police work, Serpico says accountability in leadership is the key to ending corruption.

“When I testified for the Knapp commission, it pushed corruption up the food chain. And when you have a lucrative, money-making business that profits from corruption, you’re not going to just give it up. You’re going to do whatever you have to do to keep it going," Serpico said. "That’s why we can’t just put the onus on the cop in the street. We have to watch the people at the top, because they’re the ones who should be watched, and they’re the ones who ultimately should be held accountable. The little guys can expose them, but who is going to cover them when they do? Look at all the technology we have now. We can put it to work for more transparency.”

Asked what he would do to end retaliation against police whistleblowers, Serpico listed four moves.

"First, I would pardon (WikiLeaks founder) Julian Assange to show that whistleblowers in every sector will be honored and supported, not persecuted. I would create a Lamplighter-Whistleblower award to be the highest degree of awards, because you (as a whistleblower) are not only facing an armed adversary but also an adversary that has infiltrated the police profession," he said. "Also, if we are using today’s surveillance technology to monitor the public, we should also use it to monitor the police as well. Finally, qualified immunity has to be reexamined so that it is not abused as an escape clause for brutality and manslaughter.”

Jason Williams

New Orleans District Attorney, former defense attorney and city councilman

New Orleans since 2011 has been under a U.S. Justice Department consent decree, a legally binding agreement that forced the city to change policing patterns and practices. Williams was sworn in as district attorney this year after spending two terms on the New Orleans city council. He has previously done pro bono work with the Innocence Project of New Orleans.

Williams said accountability promotes better police work because "it allows good police officers to shine." But he added that prosecutors' offices should set the standard.

"By me engaging in prosecutorial reform, that’s me saying that I realize we have some sweeping around to do in front of our own front door," he said. "We started a civil rights division in my office because we saw we had administrations here that caused harm in the past by hiding evidence, not turning over evidence that they should have in a timely manner. When (police) see us voluntarily accepting responsibility for the harm that we caused, then it seems less finger-pointy.”

For these reforms to work, Williams said, police departments have to lean on public safety as a priority over making arrests.

"If the local prosecutor defines success as accepting 90% of the reports police send us as fact, they’re abdicating their role as the architect of the criminal justice system. When the prosecutor doesn’t point out ‘Hey, there’s constitutional violations here’ or 'Hey, there was racial profiling here,’ and just accepts these cases, then they’re abdicating their responsibilities," Williams said. "Instead, prosecutors need to call these things out when they see it and then report this activity to the leadership of the police departments. Success should not be measured in the number of convictions and the lengths of sentences, it should be measured in how many times you’re doing it right and are you closing the big cases by getting the right people in jail and are you doing it in a constitutional way. We’ve caught our fair share of hell trying to tell the truth about these things, but it’s necessary.”

DeLacy Davis

Former New Jersey police officer, founder and executive director of Black Cops Against Police Brutality

Tom Devine

Executive Director of the nonprofit Government Accountability Project, a whistleblower protection and advocacy organization

Devine said he has made great strides in helping get whistleblower protections for people in a variety of other professions, but police and union lobbyists have boxed police officers out of most of those reforms.

“Law enforcement whistleblowers have always been kind of left off the bus,” Devine said.

Devine hopes that will change with a bill from Rep. Gerry Connolly, D-Va., that is designed to provide a number of protections specifically for law enforcement whistleblowers, including the creation of an independent federal inspector general's office to field officers' complaints about their coworkers anonymously. "It would be the gold standard, not just for police whistleblowers, but whistleblowers period,” Devine said.

The move would also neutralize the impact of the 2006 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Garcetti vs. Ceballos, which held that public employees had no First Amendment rights when they report misconduct on the job.

“It was a disastrous erosion of free speech rights, especially because the previous standards protected duty speech in matters of great public importance, which is particularly relevant for law enforcement when you consider cases of police brutality and other forms of misconduct that affect the public," Devine said. "So you can file a suit, but after you file a suit it’s extremely difficult to win because the department will say your speech was within your job duties so you have no rights. Departments use it to make it look to the public like they’re rooting out corruption by saying ‘Look, we have policies that give officers a duty to report.’ But in reality it’s a duty that’s honored about as often as someone holding a winning lottery ticket.”

Samuel Walker

Emeritus professor at the University of Nebraska and leading scholar on police accountability

Walker said he hasn't seen any organized national opposition to provisions in police union contracts that make it easier for officers to cover up misconduct.

“What the police unions figured out is that they could get much more through the union contracts than through state laws, because the contracts are negotiated in secret. No public participation. There needed to be material for city negotiators that would say, here are the things you don't want to allow, you don't want to agree to, in union contracts. Because you will pay a price for them later. You will protect officer misconduct, and some of those officers are going to go on to do very bad things, and the city will be sued, and you’ll pay out lots of money, and also just continue to damage police/community relations. So there’s been a terrible, long-term impact.”

The first step in protecting police whistleblowers would be for the U.S. Attorney General's Office to convene a conference or workshop to examine the problem, Walker said.

"It's a big problem, it's a serious problem, it undermines the integrity of our justice system, and no one has done anything about it. How can you research something when the dynamics of the system keep even good people quiet?" Walker said. "The U.S. Attorney General, this is something that only a person in that position can really take on. Because I'm sure there are a number of chiefs across the country who are horrified by this, but they don't know where to begin and need some mechanism to help them see that there are others facing the same dilemma."

Mitchell Davis

Chief of Police for the Village of Hazel Crest, Illinois and President of the Illinois Association of Chiefs of Police

Benjamin Crump

Civil rights attorney

Crump and fellow civil rights attorney Antonio Romanucci, who both represented George Floyd’s family, told USA TODAY in February that an end to qualified immunity would end the code of silence.

At the time, they hoped that abolishing the law that shields police officers from liability in most use of force cases would be part of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act. But the bill stalled in the Senate. Crump now says whistleblower protections will have to come from the state and local level, although he believes there are some things President Joe Biden can do right away.

“I think we should make it a federal offense to lie on a police report. That would be a huge deterrent. We would need legislative efforts for that, but in the meantime, the Biden administration could issue an executive order, which would remain in effect for as long as he is president," Crump said. "There has been tremendous progress on the local level. And there are things, like the database (of officers who have committed misconduct), we don’t need Congress for that. We don't need Congress for the Biden administration to issue an executive order to keep statistics on who the police are killing.”

Like Walker and others, Crump believes that police union contract negotiations need to be subject to greater transparency.

"So often, the police unions continue to win all of these negotiations in ways that protect the status quo where Black and brown people keep getting the brunt on everything that’s wrong with our system. And everything is justified by them winning," Crump said. "If someone is killed then it’s justified, and the killings and the incarcerations are what is keeping this capitalistic engine going to fuel the prison industrial complex, to profit from Black and brown people."

Sara Jones

Criminal defense attorney based in Lake Wales, Florida

Jones has been publicly critical of police practices in her area and advocated for police body cameras and other police accountability measures. She said local law enforcement has retaliated against her efforts by launching bogus criminal investigations against her.

Video evidence helped a client in one of Jones’ recent cases prove that a police officer lied in his arrest report, and she has defended several clients who have gotten their charges reduced or dropped in cases against an officer accused of beating and using racial slurs against Black residents.

“I think one of the things that has been important to me is having a requirement that police officers live in the communities they police in. Knowing the people you are policing allows us to release the 'us versus them' mentality that’s been so ubiquitous and made police departments such an insular community,” she said.

Randolph Thomas

1980s whistleblower from Louisiana

Hamid Mehran

Retired staff economist, Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Before Mehran retired from the Federal Reserve five years ago, he worked with banks to root out corruption within their ranks and saw how effective financial penalties were in deterring wrongdoing. In an op-ed piece for the Philadelphia Inquirer in July, Mehran outlined his plan for how the same principles could force officers to speak out.

Mehran proposes that police officers put up to 3% of their annual salaries in a deferred fund. They would get the money back with interest if they leave a department with a clean record, but forfeit the money if they have committed misconduct or failed to intervene or to report the bad acts of fellow officers.

“You want to be proactive on mitigating the small things before they turn into big problems for the employees and the institution. This point was underscored when I interviewed many bankers. For example, an employee makes an error and does not want to get help because the problem seems easy to fix. Or, the employee may be concerned about how revelation of the mistake would impact his or her career and would ignore the impact on others in the organization as well as the public," Mehran told USA TODAY. "As a result, he or she tries to hide the mistake, which has the potential to become a slippery slope. In extreme cases, everyone in the organization would lose. So if you start taking the approach of seeing something and dealing with it right away, you avoid the slippery slope. You’re not hurting your colleague. In fact, you’re helping that colleague by preventing something worse."

Elgie R. Sims, Jr.

Illinois state senator

Sims was the sponsor of the Illinois Safety, Accountability, Fairness and Equity-Today Act, known as the SAFE-T Act, which passed the Illinois Senate in January as the most far-reaching police reform bill in the state’s history.

The legislation, which mandated police use of body cameras and will phase out the state's cash bail system by 2023, also included provisions that would allow the state police certification board to decertify police officers found to have committed acts of retaliation against their coworkers. The bill also broadened the definition of retaliation beyond just firing whistleblowers.

Other provisions include a duty to intervene statute for officers who witness misconduct and measures aimed at stopping embattled officers from resigning and moving to other departments while they’re under investigation for misconduct. Critics of the bill say a trailer bill that passed in July rolled back significant portions of the original language designed to penalize untruthful cops, but Sims says he still believes the bill is a trailblazer for state-level reform.

“There are some folks who are unable or unwilling to report. That’s why we built in a whistleblower protection. You should not have a pause about saying and doing the right thing. Good officers despise bad officers. Reform is a journey, it’s not the destination," Sims said. "Was this the first reform? Absolutely not. But it’s certainly the most comprehensive act that has passed and we think it will have an impact on law enforcement nationally."

Abby Bakos

Civil attorney for Nicole Lurry, the widow of a Joliet, Illinois man who died after a police encounter caught on a video exposed by a whistleblower

Shannon Spalding

Chicago Police Department whistleblower

Spalding is starting a nonprofit organization designed to connect police whistleblowers to mental health and legal resources. She said she hopes more groups like hers can help guide whistleblowers through the process of speaking up.

“Two years ago I was contacted by the U.S. embassy in Kosovo and helped them get whistleblower protections there, and now Kosovo has stronger whistleblower protections than we do here in the U.S.," she said. "In law enforcement, we are supposed to be held to a higher standard, but officers are very limited because they’re afraid. We need to change the narrative. Currently we have to report to the higher ranking officers, and in many cases they’re the very people involved in the corruption, and there needs to be a safe place to report corruption.”

Austin Handle

Whistleblower against Dunwoody, Georgia, Police Department and vice-chair and founding board member of The Lamplighter Project

Handle was just 24 when he was fired from his department days after he posted a TikTok video hinting at allegations of internal corruption. Handle went on to become one of the founding board members of the Lamplighter Project, an organization that aims to provide peer counseling and support to whistleblowers.

This summer, Handle became the youngest person on a list of 30 law enforcement officers calling for Congress to pass federal whistleblower protections. As part of the Lamplighter organization, Handle speaks to police officers across the country to offer advice and support.

"Policing today tries to make people into robots — who are following policies and procedures like they’re doing computer coding — instead of individuals," Handle said. "But if you really look back at it, constables from Great Britain were night watchmen that were not paid, that were community members and were stakeholders who worked to patrol their communities and uphold the values of their community. People are more willing to speak out about corruption in a community they hold a stake in. The problem with police in most places now is they're not stakeholders, they’re just people who have a job."

Carl Cavalier

Louisiana State Police whistleblower

Samuel Lee Reid

Executive Director, Atlanta Citizen Review Board

Reid told USA TODAY in February that he was encouraged by the Atlanta police's implementation of a bystander intervention program, which trains officers on how to recognize the situations that might trigger acts of misconduct while they’re in the field and gives them strategies for when and how to intervene when they see a fellow officer doing something wrong. Programs like these, which are gaining popularity around the country, are designed to prevent incidents from happening in the first place so there won’t be a need for a whistleblower later.

"Police departments need to cultivate support for people to do the right thing," said Reid, who heads one of the only citizen review boards in the nation with power to subpoena officers to testify in the board's investigations into misconduct claims.

In 2014, the New Orleans Police Department began a program called Ethical Policing is Courageous, or EPIC. Mary Howell, one of the architects of the program, said a goal of the program is to redefine loyalty "so that if an officer doesn't intervene to prevent misconduct, they are being disloyal to other officers."

Elsewhere, programs like Active Bystandership for Law Enforcement, or ABLE, seek to accomplish the same shift in behavior. Reid believes programs like these will be tough to ingrain in law enforcement, but are necessary.

"I understand the challenge, being in the military, playing sports, having fraternity brothers. I get the sense of brotherhood and wanting to support your brothers," he said. "But with the enormous power that comes with policing to take life and liberty there’s a larger expectation that we have the best officers on the street. Policing is such a big public endeavor that it requires much more accountability, because there are no go backs it’s hard to correct these things after there's been a loss of life or liberty."

Daphne Duret, Gina Barton and Brett Murphy are reporters on USA TODAY's investigative team. Jarrad Henderson is a USA TODAY Senior Video Producer.

Daphne Duret is a 2021-22 Knight-Wallace Reporting Fellow at the University of Michigan. Contact Daphne at dduret@gannett.com, @dd_writes, by signal at 772-486-5562. Contact Brett at brett.murphy@usatoday.com, @brettMmurphy, by Signal at 508-523-5195. Contact Gina at gbarton@gannett.com, @writerbarton.

Corrections & Clarifications: An earlier version of this story misspelled the name of a criminal defense attorney based in Lake Wales, Florida. Her name is Sara Jones.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Police whistleblower: Solutions to end code of silence, retaliation