Changing music: How a Mercyhurst professor became the biographer for a revolutionary inventor

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In December 2009, Mercyhurst University music professor Albert Glinsky received an unexpected phone call that would alter the course of his life.

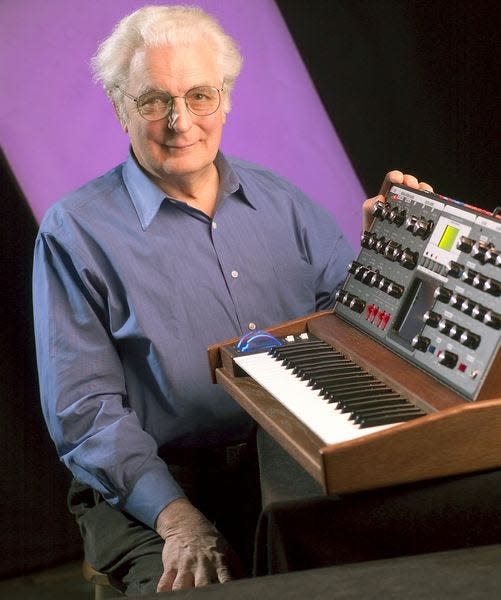

On the other end of the line was Michelle Moog-Koussa, executive director of the Bob Moog Foundation, asking if Glinsky would be willing to write a definitive biography of her father, Robert Moog, the inventor of the Moog synthesizer.

“It came out of left field. I wasn't expecting it,” Glinsky said on a video call from his home office in Erie. “It was one of those ‘Hello, is your name Albert Glinsky? Oh, yes. You just won the lottery’ kind of calls. One of Bob’s favorite quips was that he got into the electronic musical instrument business like someone slipping backward on a banana peel. And so I joke that I became Bob Moog’s biographer like someone slipping backward, because it just kind of happened one day and next thing I knew, I was writing his biography.”

Twelve years, 496 pages and countless hours of interviews later, that biography, “Switched On: Bob Moog and the Synthesizer Revolution,” was published by Oxford University Press on Sept. 23.

The idea for the book hardly came out of nowhere. Though Glinsky concedes that he didn’t know Moog well, the inventor was a valuable source for Glinsky’s previous book, “Theremin: Ether Music and Espionage” (University of Illinois Press, 2000), a biography of the pioneering Soviet scientist, inventor and spy that won an American Society of Composers Deems Taylor Award in 2001. Moog, who died in 2005 at age 71, even traveled to Erie in 2000 for “The Continuous Wave,” an exhibition of electronic instruments at the Erie Art Museum, where he delivered a whimsical and entertaining lecture-demonstration.

Glinsky, 69, was careful to incorporate his subject’s informal manner into the new book.

“Bob Moog was a fun person and very freewheeling in his language,” Glinsky said, “and the book had to match the spirit of who Bob was.”

Yet this is a serious and thoroughly researched analysis of the life and work of a man who arguably changed the course of music.

Erie's Chris Vrenna: From Nine Inch Nails, Marilyn Manson, Gnarls Barkley to college instructor

Research, interviews and documents galore

The author, who has a doctorate from New York University in composition specializing in electroacoustic music, sifted through a mountain of articles, patent applications, circuit designs and other primary materials before writing a word. Beginning with his first research trip in 2010 to Asheville, North Carolina, where the Moog Foundation is headquartered, Glinsky conducted 65 interviews with sources, some that took several days to complete. Once, Glinsky and his wife, Linda Kobler, whom he collaborated with on the project, showed up at an Asheville Kinko's at 2 a.m. to copy 8,000 pages of documents that were kept in the basement of Moog’s home.

Among the most interesting memorabilia Glinsky discovered were letters written to Moog's first wife while both were studying at different colleges.

“Those were wonderful," Glinsky said, adding that some contained sketches, one of which is reproduced in the book. “I won't say anything more than that. It's just very, very funny.”

But Glinsky’s scholarship led to uncovering some new information about Moog’s innovations and even busted a few myths. One of them was the mystery around whether Moog or California inventor Don Buchla was the first to build a voltage controlled modular synthesizer (spoiler alert: it was Moog).

Glinsky also addresses the rather open secret that Moog never made much money from his synthesizers.

“Bob Moog was broke most of his life,” Glinsky said. “He also slipped backward on a banana peel into founding an entire industry himself because he had no experience in synthesizers until he created the first practical model. So while people were gobbling up his synths, nobody realized that the thousands of the employees and the overhead was really a losing proposition for him most of the time, and he had to be bailed out.”

Moog was, in essence, the kind of basement-workshop tinkerer who built things for his own pleasure and ended up creating a new technology that its users harnessed to create a new way of making music.

Moog's synthesizers change music culture

“He made synthesizers practical for the average musician and the average consumer,” Glinsky said. “He really put it all together into a practical system, and that's the genius of it. That's why the book is called ‘Switched On,’ because he switched on the musical culture of the time.”

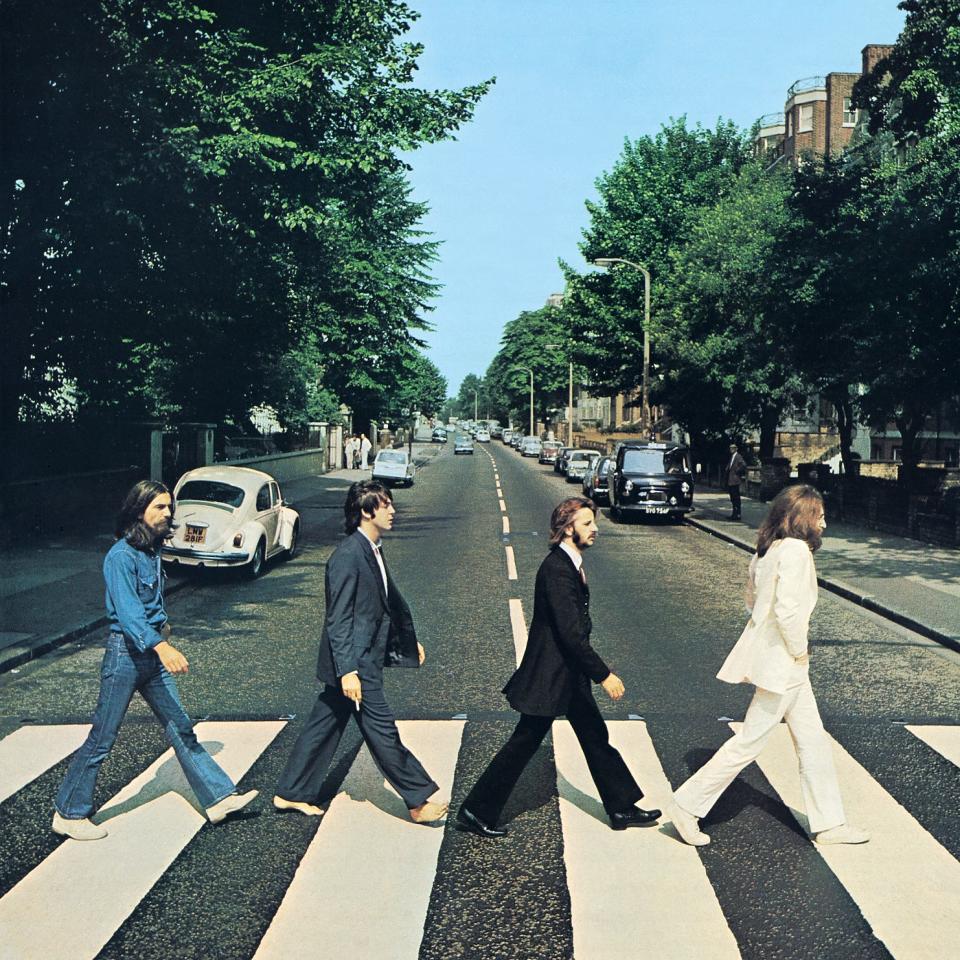

That culture diffused from early projects such as Wendy Carlos’ “Switched-On Bach,” a 1968 release that reached No. 10 on the U.S. Billboard 200 charts, to hits by progressive rock bands such as Emerson, Lake & Palmer, and soon enough, to bands everywhere. The Monkees were one of the first groups to use a Moog synthesizer in the recording studio, and The Beatles used it on their "Abbey Road" album in 1969, most notably in the song "I Want You (She's So Heavy)." Nine Inch Nails’ hit single “Head Like a Hole,” which featured a Moog synthesizer, was released in 1990. Soundtracks from “A Clockwork Orange,” “The Shining” and “Tron” also featured Moog's invention.

After The Pulse: Erie's Bob Burger reaches musical height by playing amongst rock royalty

Music journey: Erie bassist 'Fuzz' Samuel's rich musical life: Jamming with Hendrix, CSNY, local musicians

One of the most memorable uses of Moog’s invention was as a lead player in the eerie, electronic soundtrack of Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 film “Apocalypse Now.” That connection, and a friendship struck up between the legendary director and Glinsky, led to Coppola writing the foreword to “Switched On.”

“He contacted me in 2011 about my Theremin book and I met him in New York, and we were later his guests in California, “ Glinsky said. “His father (Carmine) used the Moog as one of the key elements in his score for ‘Apocalypse Now.’ So when it came time to decide who should write the foreword, he was the first person that I thought of. I really didn't expect him to say yes, but he didn't hesitate. I thought that was just great.”

Tech/TV personality: Katie Linendoll hits country music charts, credits Erie roots for success

Glinsky's version of 'crop rotation'

“Switched On” has consumed much of Glinsky’s energy since retiring as a full-time professor at Mercyhurst University in 2016. Yet he still has composition students, teaching one day a week, and he continues to compose new music.

“I wrote two pieces in the middle of writing the book, but yes, I'm very anxious to get back to full-time composing,” he said. “Joni Mitchell talks about ’crop rotation,’ because she will put out an album and then take a couple years off from music and do painting and then take time off from her art for a couple of years and put out another album. And so the last couple of decades for me have been crop rotation: author, composer, author, composer, author, composer.”

About the book

Title: “Switched On: Bob Moog and the Synthesizer Revolution”

Author: Albert Glinsky

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Pages: 496

Release date: Sept. 23

List price: $39.95 hardcover

Erie author: Hans G. Myers' book aims to give Civil War hero Strong Vincent his due

This article originally appeared on Erie Times-News: Bob Moog biographer Albert Glinsky writes book on synthesizer pioneer