Chappaquiddick After the Bridge

This article was originally published in the February 1972 issue of Esquire magazine. To read more from the Esquire archive, visit Esquire Classic.

The fastest selling book in Edgartown this summer, two summers after Mary Jo Kopechne’s death, is a work called Teddy Bare. The gift-shop book nooks don’t carry Teddy Bare (subtitled The Last of the Kennedy Clan); in fact the only place in town that will sell it is John Farrar’s Turf & Tackle Shop on Main Street, where, to the right of the cash register in the middle of the store, two sections have been set aside to display copies of Teddy Bare. The cover is a harsh two-color job, wide bands of black and yellow. On it is a photograph of Teddy Kennedy in a self-absorbed mood. Teddy Kennedy’s face is yellow.

A customer in the shop, wearing the tomato-red slacks of the Edgartown Yacht Club set and inspecting surf-casting reels, tells me that “Zad Rust,” the author of Teddy Bare, is really a pseudonym for a former prince and foreign minister of Roumania. “I understand he has some connection with the Birch Society,” the customer adds, “but when you leave out the hysterical part he makes a pretty good case against Teddy, if you ask me. Lots of people around here have read it, although you’ll see they’ll take that cover off before they’ll carry it around in public.”

“Zad Rust,” it turns out, is a Roumanian Prince. He is eighty-year-old Prince Michel Sturdza (“Zad Rust” is an anagram of Sturdza), Foreign Minister of Roumania from September, 1940, until January 19, 1941. Before World War II he was also head of the Roumanian Consulate in Riga, serving all of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, a World War I artillery captain, a diplomat in the Albanian Consulate of the Roumanian monarchy, according to his publisher, Western Islands, whose phone number in Belmont, Massachusetts, is shared by American Opinion, the John Birch Society magazine.

In his more excited moments Prince Sturdza (“Prince is a title of nobility in Roumania, he’s not actually a royal prince,” the publisher informed me) seems to envision Teddy Kennedy as a kind of American Prince of Darkness. He calls Teddy Kennedy “one of the prominent operators chosen by the Hidden Forces that are hurling the countries of Western Europe toward the Animal Farm World willed by Lenin. . . . This Force of Darkness has already brought the world near to the point of no return and to the enthronement of the Antichrist.”

As partial proof Sturdza publishes a blurry news photo blown up to full-page size with this caption: “Red Spain, 1938. Extreme left, Krishna Menon; center, Communist General Enrique Lister. . . . Is the man next to Menon John F. Kennedy?”

In the less excitable section of Teddy Bare, Prince Sturdza heaps up mounds of evidence to prove that 1) Teddy lied about Chappaquiddick; 2) Teddy was guilty of manslaughter; 3) “all the efforts of the police and judiciary authorities were directed . . . not toward discovery of its truth but toward its burial.”

Edgartown Police Chief Dominick Arena still can’t understand that kind of criticism. “How can they say I was soft on Kennedy?” the chief asks me from behind his desk in the three-room bungalow which passes as the Edgartown police station. “After all the inquests, I’m the only one who ever got a conviction on the guy, aren’t I?”

Chief Arena, a big, tall, totally amiable man, sits at a desk next to half a wall of photographs of himself in action two summers ago: facing network microphones, listening intently to press-conference questions, entering the Dukes County Courthouse the day of the conviction.

“I guess you can say I’ve become a kind of pseudo-celebrity, if you know what I mean,” he says, going through a folder of press clippings he has taken out of his desk. The chief no longer keeps his complete scrapbook of clippings and photos at the station house—it’s back home—but he still has a few mementos of interest. “I’m trying to find a picture you might be interested in. It was taken when the Arthur D. Little company, you know, that research outfit Kennedy’s attorneys hired to find out how long after the accident the girl lived, they came down to reconstruct the accident and I posed, all dripping wet in my bathing suit, just the way I was the morning I found the Kennedy car there and dived in. Actually I’m kinda glad they don’t have a picture of the actual day cause I’ve lost a lot of weight since then.

“Of course I don’t do as much public talking now as I did back then,” the Chief continued, gesturing to the press-conference pictures on his wall. “It got to be almost a joke. I remember speaking at a P.B.A. high-school-award dinner and began by saying, ‘Unaccustomed as I am to public speaking. . . .’ That got a big laugh.”

Chief Arena tells more stories about his year as a celebrity:

There was the time a German picture magazine asked him to pose for a big spread. “They had me go through the whole case again. They had me frolic with my kids, then they had me standing at the ferry slip pointing toward Chappy, they had me walk down the middle of Main Street with my hand at my gun like Wyatt Earp, they had me do everything. Well it turned out, after all this, the film they used was black and white and they wanted color, so they had me do the whole thing over again with color film this time. Any case, I never heard from them again, so when a friend of mine was going to Europe I asked him to pick up a copy. Turned out the magazine folded before they could run the spread.”

Then there was the time the Chief held a press conference for some foreign reporters and, when a man from Italy suggested Teddy Kennedy was driving to Dyke Beach with Mary Jo Kopechne “to get a little action,” he winked, which the Italian took to be a gesture of assent.

“I was joking, just sitting around chatting with these guys. Well, one of them goes off and files a story about Kennedy trying to get a little action. Isn’t that something?”

This summer the only photographers and reporters who came up to do a story on Chief Arena were a handful who arrived in mid-July for “Chappaquiddick Two Years Ago Today” features.

“I’m sure I’m gonna end up a Where Are They Now item a few years from today. I used to say one thing that might come out of this would be that when someone would say Dominick Arena, people wouldn’t think he was talking about some ice-hockey place. Well, just the other day I got a call from an off-island station about an accident and when I told ’em my name was Dominick Arena, they just said right back, ‘How do you spell that name?’ How fleeting is fame. How fleeting is fame.”

Even the hate mail has stopped coming in quantity. It used to be that every week a dozen people in America wrote Chief Arena to charge him with performing unnatural acts with Senator Kennedy and/or Mary Jo Kopechne. A dozen more would call him things like “disgusting wop Communist.” Now the infrequent letters are mainly from “regulars” the Chief has come to count on, and they are less filled with hate than with visions and theories.

“Here they are.” The Chief has pulled out a carton full of letters from under a nearby bench. “And this is only a fraction. Here’s the one I was telling you about from the religious kook. I got a couple of cards like this from her. Look, she’s got me down as an archangel.”

He hands me a foot-square white card on which there is a crudely drawn map of Chappaquiddick, with childlike clothed stick figures of men and women running this way and that over the surface of the island. There are several cars scooting back and forth and spidery handwriting filling up the empty spaces. “Postcard from the Grave,” the title of the card reads: “A Holy Water Painting inspired by Jesus and Mary, and Chief Romeo Sheppare of Miami First Archangel and Chief Dominick Arena 6th Archangel.”

“God has peripheral vision and ultra-sensitive hearing. Nothing is hidden,” the epigraph proclaims ominously.

There follows an elaborate description of a Chappaquiddick plot involving “an identical car with dummies” posing as Ted Kennedy and Mary Jo Kopechne and an impostor posing as Pope Paul VI among other things.

The Chief hands me another letter, this from a woman passionately denying the possibility that Mary Jo Kopechne had been drinking that night (a blood test had indicated she might have had three drinks). The woman advances the theory that Mary Jo had been gargling earlier that evening with Scope mouthwash, the high alcoholic content of which, she said, if accidentally swallowed earlier in the evening, could explain the blood-test result.

I asked the Chief if he had any theories of his own about what really went on that night.

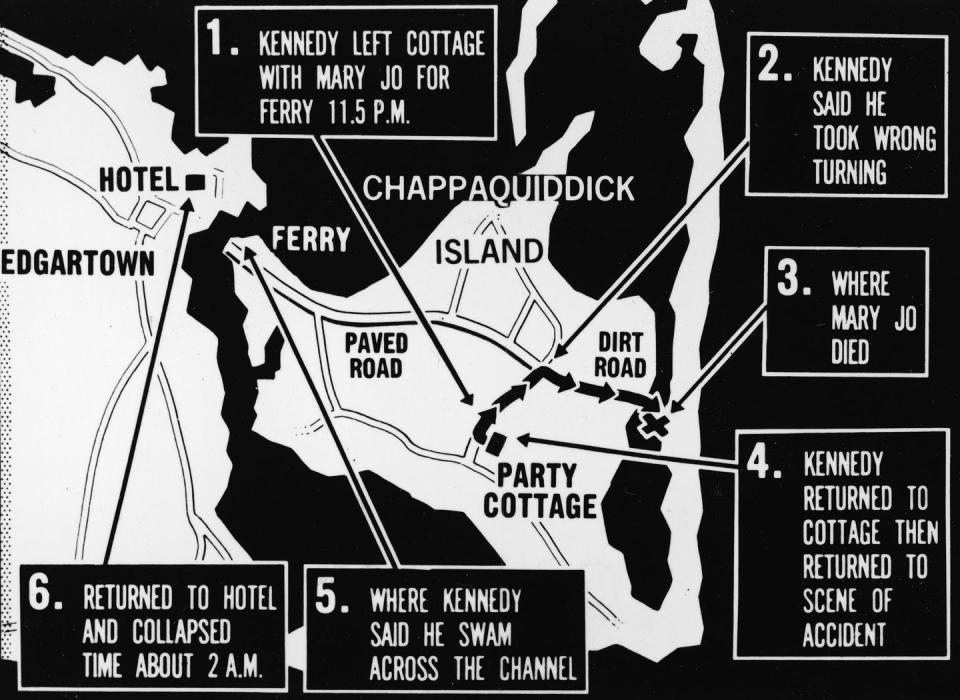

“What can I say. I have his statement. I don’t know any different. Well. . . . Little things bother me. It’s interesting that Mrs. Malm and her daughter in Dyke House less than five hundred feet from the bridge heard an engine going toward the bridge about eleven-thirty, and yet Huck Look saw a black Oldsmobile just like the Kennedy car at twelve-forty-five when Kennedy said the car was in the pond. You know they just made Huck Look sheriff, so the people around here must believe him. And why didn’t Mrs. Malm hear the car go off the bridge into the water around eleven-thirty when Kennedy said it happened. They were a few hundred feet away and heard no sounds. . . . And when you think about it there are other questions people ask—were there three people in the car, and why do all these foolish things anyway? Why not go back to one of the nearby houses? Why the delay? I’d like to believe he really didn’t know she was in the water. I can’t imagine anyone leaving someone in knowingly. . . . Why were they at Chappy the next morning? Why go over there first to make a phone call? . . . And it’s interesting that no one saw him walking down the street soaking wet to the Shiretown Motor Inn after he swam across to the ferry stop . . . that’s sort of intriguing. . . .”

A cop, one of the five year-round men on Chief Arena’s force, comes into the Chief’s office. He reports “a vehicular accident down on Dock Street.” A driver has run into a parked car, denting the fender. The injured car has been identified and the officer wants to know if he should put it out over the radio for the other men to look for the owner. The Chief points out that the men on duty now are summer specials and don’t have radios. The officer goes out.

“No, there hasn’t been any major crime here in the past two years. It’s funny, we’re still working on that case of the whaling logs being stolen from the museum, which happened a long time before Chappaquiddick. In fact, just a week before the whole Chappy incident, people were telling me about how this whaling-log case is the one that’s gonna make me. Then next week. . . . No, we get a few more illegal campers every year and a lot more nudes. Nothing serious.”

Nudes?

“Yeah, you get a lot more nude bathers night and day, these days, and the law says I gotta arrest them. It’s kind of silly if you see what people are wearing on the streets these days. You walk down Main Street and half of the girls don’t have bras. Have you been down Main Street? It’s incredible, isn’t it?”

Does the Chief plan on staying on in Edgartown?

“Actually, I’d go someplace else if I had a good offer. I grew up in a city and I think I’d like going back to the city. But I haven’t had the right offer yet.”

Sunday morning the cars of two honeymoon couples who arrived late at night can be seen parked opposite the Chappaquiddick House of the Harborside Inn, the largest hotel in town. The bodies of the two cars have been covered with soaped-on cartoons and wisecracks by the wedding parties. One car has the classic two pairs of feet bottoms arranged in the missionary position. “Put a tiger in your Bed,” “Why Buy the Cow when the Milk is Free,” and other metaphors of zoo and barn are scrawled in foot-high letters on the other car. Townspeople on the way to church cross the street to avoid them.

A raccoon’s tail has been pinned to a Raquel Welch poster. It has been pinned to her crotch and hangs down the length of the poster which is taped high up on the wall in the back room of John Farrar’s Turf & Tackle Shop. Someone would have had to use a ladder to pin the raccoon up that high. Pasted below the poster is a sticker reading, “Insert Lube Gun Here.”

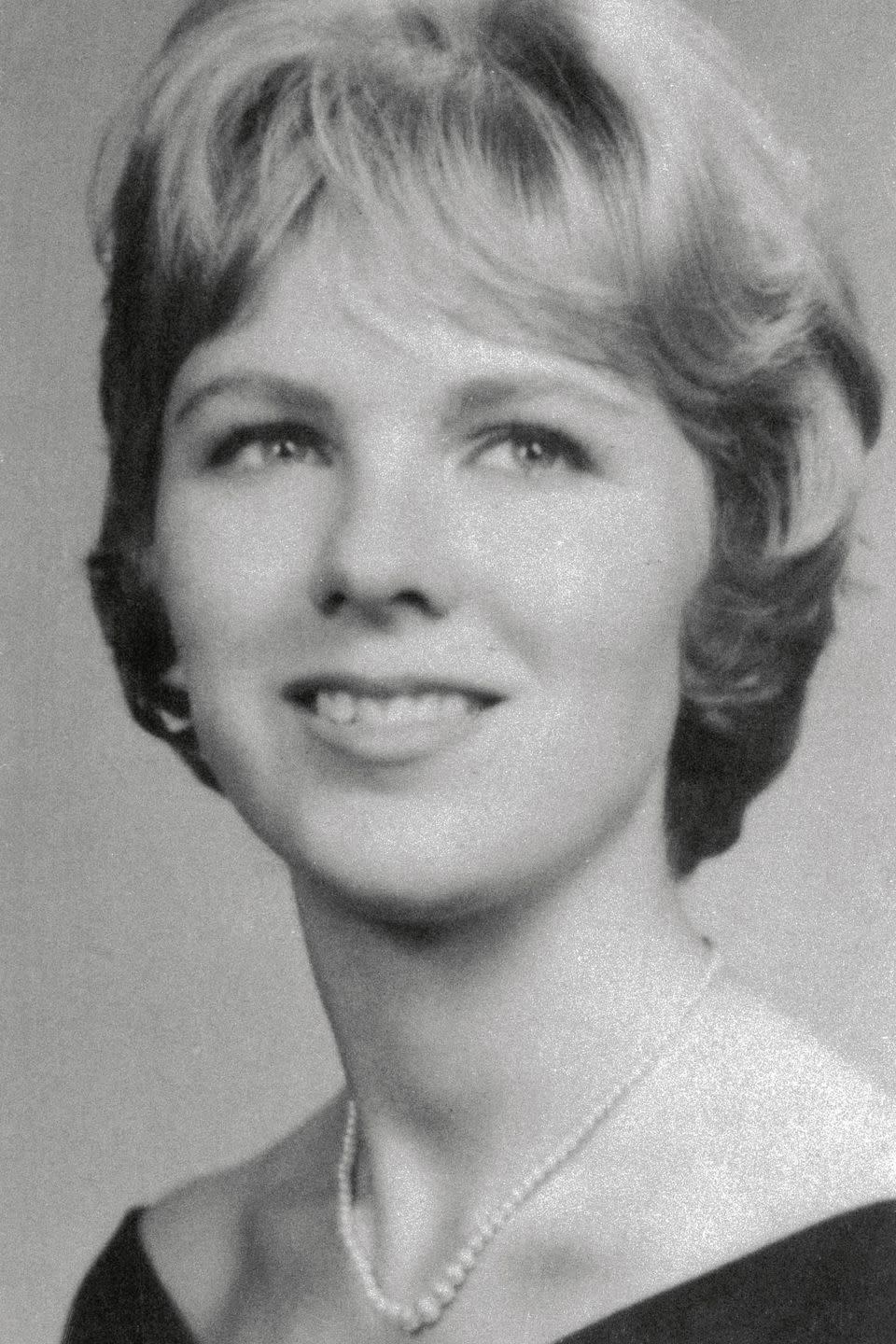

John Farrar is at his workbench in the back room fixing a reel for a gentleman surf-caster as he talks to me about Chappaquiddick. Farrar has been the only person connected with the incident who has loudly and publicly accused Teddy Kennedy of manslaughter. Farrar was the expert diver on the Edgartown Search and Rescue Squad whom Chief Arena called in to bring Mary Jo Kopechne’s body out of the car submerged in Poucha Pond. After bringing up the dead girl’s body by hand and looking into her face that morning, Farrar became obsessed with the idea that the girl had been trapped alive for hours inside the car and that if Kennedy hadn’t waited so long to call for help he, Farrar, could have brought her to the surface alive.

Farrar is a tall rangy man who looks like a cowboy even before he puts on the black cowboy hat he wears to cover his thinning hair.

Farrar is still angry about Chappaquiddick. He drinks black coffee while he talks, fixes the reel, takes short quick steps around the workbench, and makes gestures with a caffeinated jumpiness.

“There’s a lot of rabble coming here these days. The ugly American, if you know what I mean. Kennedy, although maybe he didn’t choose to, has destroyed this island. They’re thrill seekers. Deity worshipers. Sadistic souvenir hunters. It’s the unfortunate seamy side of America.”

He is also angry at people in general.

“People don’t like facts. People don’t like facts like this. People don’t want to think . . . they have to have a champion to worship. If he receives so much as a vote for President it’s a disgusting comment on America.” Farrar believes Teddy Kennedy is a liar. “As far as I’m concerned, nothing the man has said has fit. It’s a pack of lies, misfitting facts. Lies of time and tide, shall we say. . . . There was a lack of interest in her life, a complete abandonment of her that caused her death.” I asked Farrar how could he be so certain the girl lived before she drowned.

“She didn’t drown. That’s the point. She died of suffocation in her own air void. Gene Frieh, the undertaker, has said to me and said to others that he feels she did not drown but died of suffocation in her own air void. He’s done twenty-four embalmings on drowned victims and in every case they’ve been filled with water, every body cavity filled with gallons of water. Full of water from their asshole to their appetites, as Gene Frieh puts it. But Gene found about half a teacup in her. Half a teacup, that’s all. She suffocated to death. But it took her at least three or four hours to die. I could have had her out of that car twenty-five minutes after I got the call. But he didn’t call.

“How do I know she was alive that long? Because of the fact that the trunk was still filled with air and still dry, because of the fact that the trunk was the main source of air release, and because John Album, whose winch lifted the car up, saw air bubbles coming from inside the car. Oh, hello, Judith.”

A young woman with wispy blonde hair and classic W.A.S.P. features, wearing a sailing windbreaker, has stopped by to say hello to Farrar.

“Judy, I’ve just been telling this guy how morbid publicity seekers have been ruining Chappaquiddick. You can tell him. Judy lives over in Chappy.”

“Well, all I can say is that there’s traffic on the roads all the time now where there never was before. And sometimes the wait at the ferry slip is just unbearable. I’ve had to wait forty-five minutes several times. And the wait’s gone as high as an hour and a half. Some of us over in Chappy are trying to find out if we can change it so that the residents will have preference, especially in the case of cars; after all, the roads are for us, aren’t they?”

“I think they’re considered public roads, Judy,” Farrar says gently.

“Well, something should be done. It’s just awful. Have you seen the Dyke Bridge postcards?” she asks me. “You haven’t! Well, maybe they’ve sold out again. You get ’em in the drugstore.”

“Yes, they come in two sizes, large and larger,” Farrar adds. “Isn’t that morbid?”

“Well,” Judy continues, “I’ve heard some talk on Chappy that if he tries to run for President, everyone on Chappy is going to buy up thousands of Dyke Bridge postcards and send them out all over the country with one word on them—Remember.”

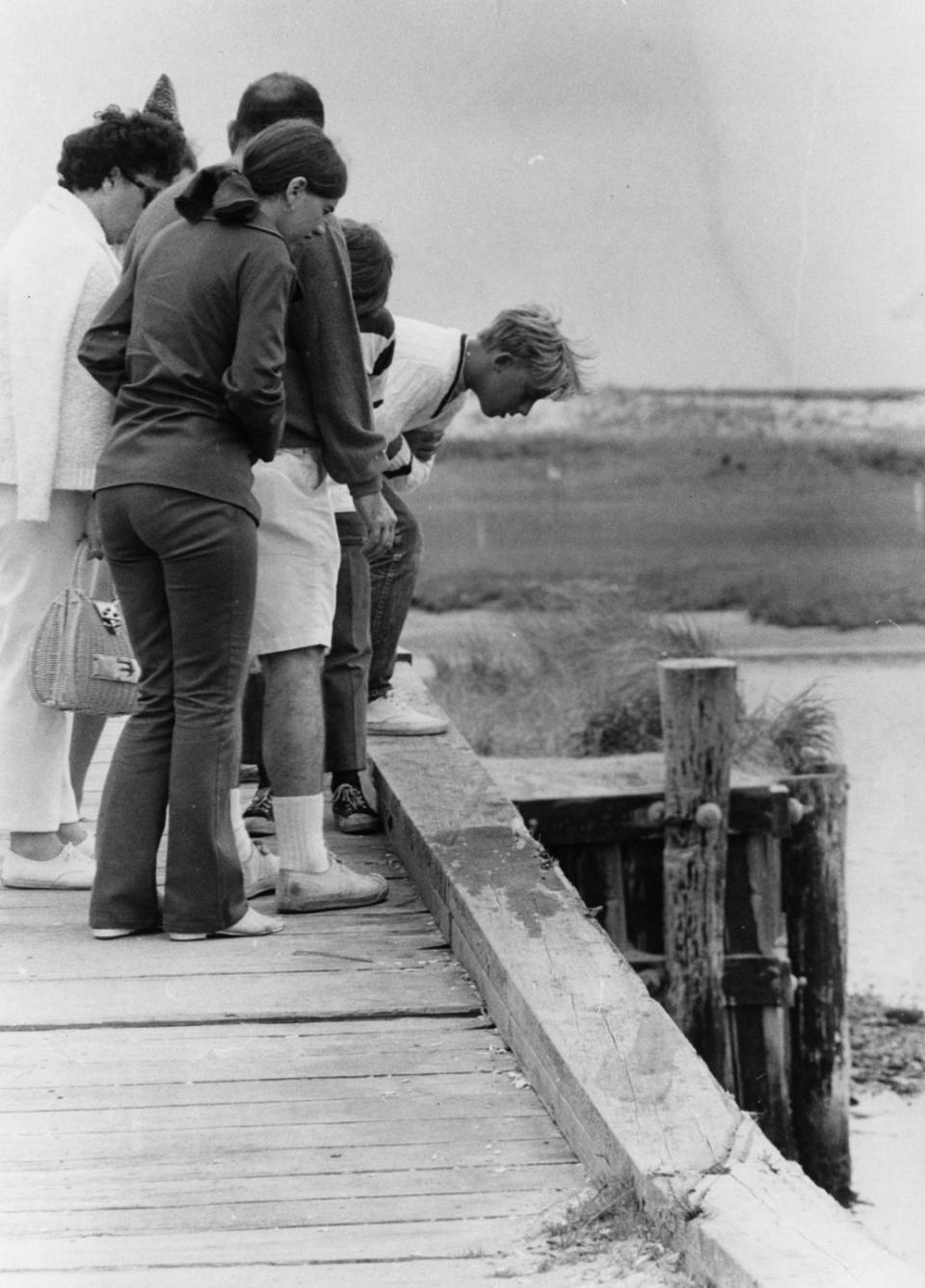

It is sunset on the Sunday before Labor Day and all but one of the tourists’ cars have left the sandy parking area in front of Dyke Bridge. A beautiful golden retriever is taking flying leaps into the tide, racing toward the pilings of the humpbacked wooden bridge. His master, a Chappaquiddick squire, has been hurling a stick into the water over and over for him to retrieve.

“Honey, enough. The dumb animal doesn’t know when to quit. It’s getting dark,” his honey-blonde wife calls softly to him from across the road in front of Dyke House where she has been removing her hip boots. They have been surf-casting on Dyke Beach across the bridge and over the dunes, and bluefish are flopping wetly in a big yellow pail next to her.

The lady has settled a soft Irish-woolen scarf around her neck against the end-of-summer evening chill. Master and soaking-wet dog arrive to load the poles and two leather-covered Thermoses into their Land-Rover.

“I’m surprised Esquire would have the poor taste to want a story about Chappaquiddick,” the squire told me after we had talked for a while. “People want to be left alone. The whole thing is in poor taste. The people who come here! Believe me, people on Chappy are more sorry he went off the bridge than he is. Have you seen what they do to the bridge?”

What they do to the bridge is carve long inch-wide slivers off it and carve wisecracks upon it. Today fresh pink gashes have been left in the grey salt-bleached wood. Most of the slivers have been sliced off the right-hand side where the wheels of Kennedy’s black Oldsmobile left the bridge. The carved inscriptions read: “Teddy Kennedy Memorial Footbridge.” “E M K & M J K.”

In the center of the bridge someone has recently nailed a two-foot-square plywood board over the largest inscription, a big red-paint heart. The outline of the heart sticks out from the plywood masking. But whoever slapped the plywood down has made it impossible to see what is painted inside the boarded-over heart.

Foster Silva, the watchman of Chappaquiddick, has twenty one-hundred-year-old heath-hen skins he would like to sell to museums and collectors.

“If you want a story, forget about that whole Kennedy thing,” he advised me, “and let me tell you about these heath hens I’ve got upstairs. You know about heath hens, don’t you?”

Heath hens are extinct, Foster Silva explained. The last surviving heath hen had lived out its lonely life on Martha’s Vineyard, expiring in 1929. “They are very valuable birds, heath hens; no one has ’em. There are maybe nine of ’em in museums in the entire world, if that. Well, one day I’m checking around the basement of this estate I manage, and I come across an old butter firkin. I open it up and inside I find twenty heath-hen skins perfectly preserved and at least a hundred years old.

“Museums would just love to have them, every one in perfect condition, but every taxidermist I went to swore they were too dry, they couldn’t be stuffed and mounted. Finally I found a taxidermist in New Bedford. Had five of ’em mounted on American chestnut. That’s an extinct kind of wood, you know. Museums would love to have these. I’d like to sell them. The trouble is no museum could afford what they’re worth. Cost me three hundred dollars apiece just to get the five stuffed. So I’m looking to get some wealthy collectors interested in buying them from me and donating them to museums like they do. Wait just a minute, I’ll bring one downstairs to show you.”

Foster Silva manages estates on Chappaquiddick. He is also superintendent of the Cape Poge Wild Life Refuge and the Wasque Point Reservation. His salary is paid by the “Trustees of Reservations,” a very exclusive private corporation which owns most of the undeveloped land on Chappaquiddick Island.

Foster Silva is also the night watchman in the summer, the night and day watchman in the winter (his is one of the seven families who stay on Chappaquiddick through the winter) for the estate owners of Chappaquiddick.

Foster Silva’s wife has a real-estate and rental-agent business, operating out of their early-American living room, which is the closest thing to a public place on an island obsessed by privacy. In the living room this stormy Labor Day afternoon are a wealthy New York surgeon and his wife. They are dressed in crisp new yachting clothes despite the small-craft warnings and hurricane threats in the air. The surgeon wants to buy property to build on and they are waiting for Foster to take them in his Jeep through a sandy back road to some acreage on the island’s south shore.

Two plump ladies sip steaming coffee and chat with the attractive surgical couple as they wait for Foster. They are Dodie, Foster’s wife, and Mrs. Sidney Lawrence, owner of a certain cottage a hundred yards down the road. Land prices have shot up in the past two years, the ladies tell the doctor. They discuss a seven-acre property an old Chappy family has put up for sale at an offering price of $25,000 an acre. A less valuable, somewhat marshy tract is mentioned as available at $9,000 per acre, but its location is disparaged.

Unlike most Chappaquiddick residents, Mrs. Lawrence isn’t reluctant to talk about “the Teddy Kennedy thing.”

“I was deprived of a summer that was very important to me in my artistic development by the whole affair,” she tells me.

Mrs. Lawrence is the widow of Sidney Lawrence of Scarsdale, New York, whose cottage down the road was the scene of the Kennedy-Kopechne barbecue party on July 18, 1969.

“I was going to have a big show that year. My husband had just given me a whole studio—he bought the old ferry-house and had it moved into our backyard for me—and I was going to have a show at the end of the season. I had a show two years previously. It was written up in the Vineyard Gazette—did you happen to see it? Some people have said it was a very beautiful write-up. One of my guests, it was just a private thing, brought a friend who was a critic and he ran out and wrote that review in the Gazette.

“But that year with all the reporters and the sightseers, with photographing at all hours of the night, with us taking them on tours, and with tourists breaking splinters off the split-rail fence, you can’t imagine. To hold a show was just impossible. Now the thing people criticized about the Kennedys to me was that they never apologized to me. Not once did I hear from them. Now, as for myself, I’m sure they must be well-mannered people— although I don’t know them—and I’m sure this must be an oversight on their part.”

Mrs. Lawrence does not believe Teddy Kennedy should become President. “Now I don’t know the Kennedys personally. I can just deduce from his public things that he doesn’t have the strength of character to be a leader. He doesn’t have the dynamics. I’m sorry he has a cross to bear, but I feel much sorrier for the Kopechnes. I think I understood her. I think she must have been a nice modern girl doing things people do. You know, I have a strong romantic streak. There is a strong romantic streak throughout my best paintings. I was pleased that some of the better reporters to whom I would show some of my paintings, not even my best but just a few I had tucked away in the studio, could see that.”

Foster Silva returns carrying a four-foot-long log on which is mounted a bird which looks like a slim version of a wild turkey.

“This is it,” he says, nodding his head down at the log between his outstretched arms. “Tell me if that isn’t one hell of a mounting job there. One hundred years old. The guy who shot ’em must have been an amateur taxidermist, they’re so well preserved. Don’t you think the museums will love them? There’s a story for you. The last heath hen.”

For more stories from Esquire's 86-year archive, visit Esquire Classic.

You Might Also Like