How Charleston Became a Magnet for Architecture Lovers

Knowing my interest in Charleston, a friend sent me a YouTube link to a film called City of Proud Memories. The 10-minute travelogue, made in 1934, was the kind of one-reeler that once accompanied feature films in movie houses. The opening shot shows a trolley car rolling down Meeting Street, but the city is portrayed as having been largely bypassed by modern life, a place of “old-time and almost an old-world charm and quaintness,” as the narrator intones. Instead of automobiles, we see horse-drawn carriages and pushcarts, while black flower vendors and street musicians stroll the palmetto-shaded sidewalks. “Papa Joe” hawks fresh shrimp, calling out his wares in Gullah dialect. The atmosphere is more like a sleepy Caribbean town than a modern American city. A rose-tinted picture, no doubt, but probably not completely inaccurate.

According to the opening credits, City of Proud Memories was part of the “Thrilling Journey” series, although I could find no record of any other episodes. The film was produced by Lorenzo Del Riccio, an Italian immigrant living in New York who had worked for Paramount Pictures in Hollywood. Del Riccio’s company specialized in travelogues, but why did he choose Charleston? The little southern city had recently come to national attention. There was the dance craze, of course. The Charleston was the popular dance of the 1920s; the Ziegfeld Follies featured it, Fred Astaire sang about it, Josephine Baker introduced it to the Folies Bergère. The dance had debuted in 1923 as a number in a popular black Broadway musical, Runnin’ Wild. The composer was the great jazz pianist James P. Johnson, who collaborated with the lyricist Cecil Mack. According to Johnson, the characteristic clave rhythm of the dance was inspired by Charleston dockworkers.

Two years after Runnin’ Wild premiered, a bestselling novel featured Charleston as its setting. The title character of Porgy was inspired by an actual black street vendor known as Goat Cart Sam, and the novel’s chief locale, a tenement called Catfish Row, was based on Cabbage Row, a set of pre-Revolutionary buildings on Church Street. The New York Times praised the novel as “a noteworthy achievement in the sympathetic and convincing interpretation of negro life by a member of an ‘outside’ race.” The author was DuBose Heyward, a Charleston native who belonged to an impoverished old-line family. Heyward and his Ohio-born wife, Dorothy, a playwright, adapted the novel into a play that had a year-long run in New York and two national tours. Porgy was hardly the first favorable depiction of poor blacks in American literature, but the play was one of the first Broadway productions to be performed by an all-black cast—at the insistence of the authors.

Even before the play opened, George Gershwin had become interested in writing a musical based on the novel, and he invited Heyward to collaborate. The pair visited Charleston together, attending black churches, where they listened to spirituals—by Heyward’s account, Gershwin was an enthusiastic participant in the singing. Heyward wrote the libretto and most of the lyrics, and the result was what Gershwin called a “folk opera.” Porgy and Bess, which premiered in 1935, was performed by a classically trained all-black cast. Although not an immediate hit, the musical was revived in the 1940s and toured internationally in the 1950s. (Porgy and Bess did not play in Charleston until 1970 because its black cast refused to perform in a segregated theater.) White Charlestonians did not take pride in their newfound notoriety. A flappers’ dance created by two black New Yorkers hardly accorded with their genteel self-image, and while Heyward was a native son, neither did his low-down novel and the subsequent play and opera.

Whatever Charlestonians thought, Catfish Row entered the American pantheon of imaginary literary places. In his novel, Heyward described the tenement: “Within the high-ceilinged rooms, with their battered colonial mantels and broken decorations of Adam designs in plaster, governors had come and gone, and ambassadors of kings had schemed and danced.” The Charleston that Heyward knew—“an ancient, beautiful city that time had forgotten before it destroyed”—was full of such remnants. Throughout the late 19th century, its built heritage (although it’s unlikely anyone called it that) had been dealt hard knocks.

The Adamesque Joseph Manigault mansion, built in 1803, was ignominiously subdivided into a rooming house. The gracious 18th-century home of Heyward’s own ancestor, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, was converted into a commercial bakery.

Despite the ravages of the Civil War, the periodic destruction caused by city-wide fires, and the disastrous earthquake of 1886, a surprisingly large number of public buildings survived: the Palladian Old Exchange, which dated from before the Revolutionary War and had been used as a post office during the Civil War; the County Records Building, popularly known as the Fireproof Building due to its pioneering fire-resistant construction, designed by Robert Mills (a Charlestonian and generally considered the first native-born American to be a professionally trained architect); the main building of the College of Charleston, with its imposing Greek temple front, the work of Philadelphian William Strickland; and Hibernian Hall, a Greek Revival building built for the Irish society by Strickland’s protégé, Thomas Ustick Walter. The presence of three leading architects—Mills would design the Washington Monument, Strickland’s Second Bank of the United States in Philadelphia ushered in the American Greek Revival, and Walter was responsible for the U.S. Capitol dome—attests to Charleston’s architectural preeminence.

The Old Exchange and the College of Charleston are featured in City of Proud Memories. Another scene shows a small, windowless structure that is identified as the “historic powder magazine.” The building wasn’t from the 17th century and it wasn’t built of tabby—lime and crushed oyster shells—as the narrator claimed, but it was the oldest surviving public building in the city. Dating from the early 1700s, the brick structure had served as a powder magazine during the Revolutionary War, and was subsequently used as a wine cellar, a printer’s shop, and a stable. In 1902, it was purchased by the local chapter of the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America, which restored it and turned it into a small museum: an important moment in Charleston, for this was the first conscious effort to preserve an old building for purely historic reasons. Ten years later, the Colonial Dames acquired the disused Old Exchange.

The concern for saving old buildings was in part a reaction to immediate threats. Despite the placid image presented by Del Riccio’s film, Charleston was not insulated from modern life. Car ownership was on the rise, for example, and the oil companies were competing to build gas stations that, on the densely built-up peninsula, inevitably meant making space by demolishing old buildings. The tipping point came in 1920, when the Ford Motor Company announced that it was going to tear down the venerable Manigault mansion and replace it with a car dealership. The hastily formed Society for the Preservation of Old Dwellings (today the Preservation Society of Charleston) forestalled the plan and purchased the house.

Another kind of threat was described by Albert Simons, one of the founders of the Preservation Society. Simons, a Charleston native and a University of Pennsylvania–trained architect, was interested in history, and long before it was fashionable he was recovering architectural fragments from old buildings facing demolition and donating them to the local museum.

“It distresses me painfully to see our fine old buildings torn down, and their contents wrecked,” he explained, “or what is more humiliating sold to aliens and shipped away to enrich some other community more appreciative of such things than ourselves.” The “aliens” were chiefly northern antique dealers, who resold the old decorative ironwork, interior paneling, and mantelpieces to collectors and architects.

The home of DuBose Heyward’s ancestor, also known as the Heyward-Washington House because the president had slept there during his week-long visit to the city in 1791, became a cause célèbre when the current owner threatened to dismantle and sell the interiors. This time the Charleston Museum joined the Preservation Society to save the building.

The Planter’s Hotel on Dock Street was a different type of conservation. The hotel had been a stylish watering hole before the Civil War—Harriet Martineau had stayed there—but it was now vacant and dilapidated. The building stood on the site of a Colonial-era theater, and after the owner donated the property to the city, Albert Simons built a theater modeled on an 18th-century London playhouse in the courtyard of the restored building. He reused period paneling and mantels recovered from a Charleston mansion. Such “fabricated tradition” would be condemned by purists today, but it is an example of the inventive spirit of these early preservationists.

Something unusual was happening. Charlestonians, perhaps for the first time in their long history, were beginning to love their city—in G. K. Chesterton’s sense. This love was manifested not only in efforts to preserve landmark properties; private individuals began to repair and restore modest dwellings, not as museum pieces but as places to live.

One of the most active restorers was the redoubtable Susan Pringle Frost. A member of an established Charleston family, an ardent suffragette, and a leading founder of the Preservation Society, Frost was also a real estate agent. In that role she bought decaying historic properties, renovated the houses, and resold them. Her interest in the past often outweighed her business judgment.

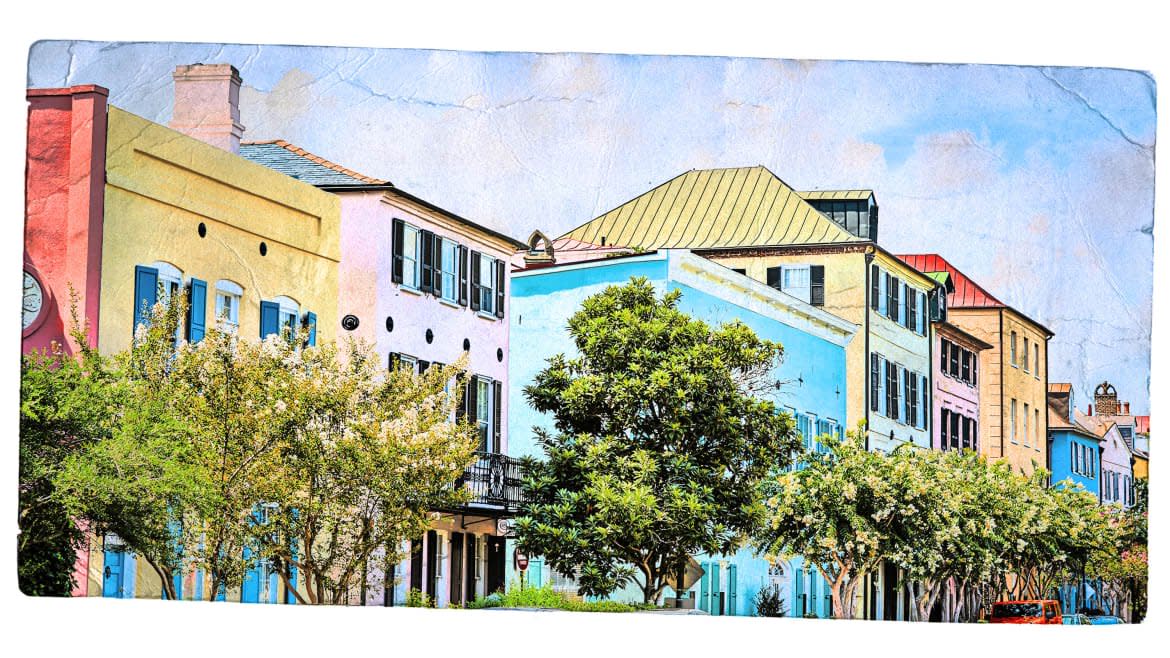

“I have never commercialized my restoration work, or my love of the old and beautiful things of Charleston,” she told an interviewer. “I have lost heavily on Tradd Street.” Frost was referring to her efforts to restore an entire portion of one of the city’s oldest streets. Around the corner, on East Bay Street, was another of Frost’s projects, a row of 18th-century houses. Subsequent owners painted the facades in different pastel colors—another “fabricated tradition”— giving rise to the name Rainbow Row.

Not only Charlestonians came to love Charleston. During World War I, unable to vacation in Europe, wealthy northerners began wintering on the Georgia coast, and on the way they discovered the Low-country. Owning a Carolina plantation became fashionable, so much so that Simons referred disparagingly to “Wall Street planters.” Despite the complaint, northern money played an important role in preserving the city. New Yorkers, especially, were prominent: Solomon R. Guggenheim bought and restored a mansion on East Battery; the celebrated architect John Mead Howells made his winter home in a renovated historic house on Tradd Street; and Loutrel Briggs, a landscape architect who would design many gardens in the Charleston area, bought and restored the Church Street tenement that was the model for Catfish Row.

Piecemeal conservation was all very well, but it was obvious that preventing further indiscriminate destruction of old buildings, and the introduction of intrusive uses such as gas stations and car dealerships into the historic district, required some sort of legislation. It was obvious that the historic buildings were important to the growing tourist industry, but the city could not simply ride roughshod over the rights of individual property owners.

The solution lay in a new type of municipal regulation: zoning. In the early 1900s, the U.S. Supreme Court had upheld the right of cities to regulate land use through zoning, and most states adopted laws that enabled local governments to enact such ordinances. In 1931, as part of a city-wide zoning plan, and with the active support of preservationists such as Frost and Simons, the Charleston city council created a so-called historic zoning district at the tip of the peninsula, the city’s oldest neighborhood.

For the first time in an American city, zoning was used to preserve old buildings. The ordinance was based on a groundbreaking insight: that the historic sense of a place was not the result only of individual landmarks but of the experience of entire neighborhoods. What became known as the Charleston ordinance was subsequently copied by other cities, both small and large: Annapolis, Georgetown, and Saint Augustine, as well as New Orleans, Boston, and Philadelphia. It was at this time that the city created the bar to oversee implementation of the historic ordinance.

How did a small, poor, provincial southern city become a pioneer in historic preservation? Robert R. Weyeneth, a historian at the University of South Carolina, has identified several reasons. The first was the city’s early history of great wealth followed by great poverty, the former producing some of the most refined colonial and antebellum urban buildings in the country, and the latter ensuring their survival. As we have seen, the old-line Charleston elites resisted change, and modernization largely bypassed the poor city. This had the effect of preserving the streets and buildings.

In the early 20th century, most fast-growing American cities showed little concern for their own history as they developed new residential areas and new commercial centers that left their old downtowns behind. Not Charleston. In 1930, the city was barely larger than it had been in the 19th century, the downtown was still the downtown, the wealthy neighborhoods remained at the tip of the peninsula, and the working-class neighborhoods were farther north. The city skyline of church steeples was unmarred by high-rise buildings. Economic lethargy only partly explains Charleston’s preservation of the past, however. City of Proud Memories describes a place “where tradition reigns supreme and the possession of a proud old name is the proudest thing a man can have,” a reminder of the enduring importance of ancestry among the Charleston elite. As Weyeneth observes, the “preservation of local heritage was frequently inseparable from preservation of family history.”

This interest in preserving the past was further encouraged by a cultural flowering known as the Charleston Renaissance. “Renaissance” may be misleading—Charles Town was never a cultural mecca. It may have been the fourth-largest city in the colonies, but since more than half its inhabitants were prohibited by law from learning to read and write, in terms of an active cultural life it was more like a small town.

Moreover, the boomtown atmosphere, while it encouraged conspicuous consumption—including building and furnishing fine homes—did not necessarily stimulate intellectual pursuits, as Harriet Martineau had observed. The wealthy city produced no Emersons, Thoreaus, or Hawthornes.

The College of Charleston was founded as early as 1785, but for years it attracted few students because wealthy families sent their children north to be educated—to New England and as far away as Britain. During his travels, Olmsted commented on the generally low level of southern culture: “From the banks of the Mississippi to the banks of the James, I did not (that I remember) see, except perhaps in one or two towns, a thermometer, nor a book of Shakespeare, nor a piano-forte or sheet of music; nor the light of a… reading lamp, nor an engraving or copy of any kind, of a work of art of the slightest merit.”

The literary side of the 20th-century cultural flowering was represented most prominently by DuBose Heyward, who also cofounded a local poetry society. The visual arts included a group of local painters such as Alice Ravenel Huger Smith and Elizabeth O’Neill Verner, who started magazines, sketching clubs, and art schools. Northern painters such as Childe Hassam and Edward Hopper “discovered” Charleston and added to the mix.

It was natural that architects should be drawn into this circle. Smith and her architect father together wrote The Dwelling Houses of Charleston, South Carolina (1917), a thick compendium illustrated with her evocative drawings. The book was published by Lippincott in Philadelphia, and was instrumental in bringing the city’s historic architecture to national attention. Dwelling Houses included photographs and drawings by Albert Simons, who taught art appreciation at the College of Charleston and, with his architectural partner, Samuel Lapham, Jr., edited a comprehensive survey of the historic district’s early buildings. Simons’s cousin, Samuel Gaillard Stoney, produced a similar study of Lowcountry plantations.

Old buildings were not only cherished architectural treasures— and family heirlooms—they were also reminders of a vanished way of life. To V. S. Naipaul, who visited Charleston in the 1980s, southerners’ attitude toward the past was not simply nostalgia but a kind of cult. “It wasn’t only the old houses and the old families, the old names, the antiquarian side of provincial or state history,” he wrote. “It was also the past as a wound: the past of which the dead or alienated plantations spoke, many of them still with physical mementoes of the old days, the houses, the dependencies, the oak avenues. The past of which the more-black-than-white city now spoke, the past of slavery and the Civil War.”

To black Charlestonians, the past meant something quite different, of course. The two perspectives remained separate. Although writers such as Heyward were sympathetic to black culture, the Charleston Renaissance was strictly a white affair. Even the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals, which was dedicated to the collection, transcription, and performance of Gullah gospel music, and of which Heyward was a member, was all-white.*

A talented black painter such as Edwin A. Harleston, a Charleston native who was a graduate of the art school of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and thus better trained than most of his white Charleston contemporaries who were self-taught, worked in isolation. In 1926, he was invited to exhibit in the Charleston Museum by its director, but the invitation was quickly rescinded by the museum trustees. Although the museum played an important role in preserving the past, throughout most of the 1920s that institution, like the public library, was off-limits to black Charlestonians.

Although the Charleston Renaissance pre-dated the better-known literary Southern Renaissance, except for Heyward, none of its figures achieved national prominence. Nevertheless, in a small city such as Charleston, with its overlapping social circles and interrelated established families, the effect of this artistic activity was significant, especially as the focus of the movement was the city itself. As Weyeneth puts it: “Artists and writers alike discovered a sentimental charm in the crumbling structures of the old city, and they created images that promoted a powerful, nostalgic aesthetic.”

It’s easy to pooh-pooh nostalgia, but the attitudes toward the past that were formed in the Charleston Renaissance had an important effect on the city. While other cities embraced urban renewal in the 1950s and 1960s in the name of progress, Charleston, secure in its backward-looking self-importance, stubbornly resisted change and maintained its old ways. The sometime laborious procedures put in place by the historic ordinances and the bar prevented the wholesale destruction of downtown neighborhoods that was a common feature of so many American cities, and despite the occasional high-rise apartment building, the peninsula largely preserved its historic scale. Moreover, the nostalgic aesthetic provided the foundation for the economic revival of the city as a major destination for holidayers and cultural tourists. In the process, it also paved the way for Historic Renovations of Charleston, Tully Alley, and the building adventures of George Holt and his friends.

Reprinted from Charleston Fancy: Little Houses & Big Dreams in the Holy City by Witold Rybczynski, published by Yale University Press © 2019. Reprinted by permission. The publication is available at Yale Books.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.