Charlotte has a new arts plan. Will it be enough to keep museums and artists afloat?

Four years ago, just after Mecklenburg County voters rejected a sales tax increase that would have ensured a steady stream of money for arts and culture in Charlotte, some of the biggest arts organizations in the city were in crisis.

The Mint Museum had a nearly $3.4 million deficit. The Charlotte Ballet, the Charlotte Symphony and Discovery Place museum all reported net losses. Combined, those four organizations were $7 million in the red in 2019.

“We’re going to be closing buildings on Tryon Street if something doesn’t change,” one arts supporter remembers City Manager Marcus Jones telling City Council members.

The Charlotte City Council moved quickly to find help. It created a new arts and culture board to distribute funds and rallied The Foundation For The Carolinas to help with private fundraising, committing $12 million per year to the arts through an Infusion Fund of private donations matched by public dollars. The Band-Aid plan was intended to be only a temporary fix while a permanent solution was devised.

Now, nearly three years into the transition to a restructured system for funding arts in Charlotte, the city is at another crossroads: The City Council voted Monday to accept the Charlotte Arts and Culture Plan presented by the city-formed Arts and Culture Advisory Board.

The plan includes a list of eight priorities the board urges the city to focus on, along with broad strategies for achieving results. High among the priorities is ensuring that groups historically marginalized in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg arts and culture sector receive “equitable, accessible and inclusive support and funding.”

But major questions persist: Who, exactly, will fund the arts sector? How much will be needed? And who will be in charge of distributing funds?

‘Unspecified amounts … with unspecified implications’

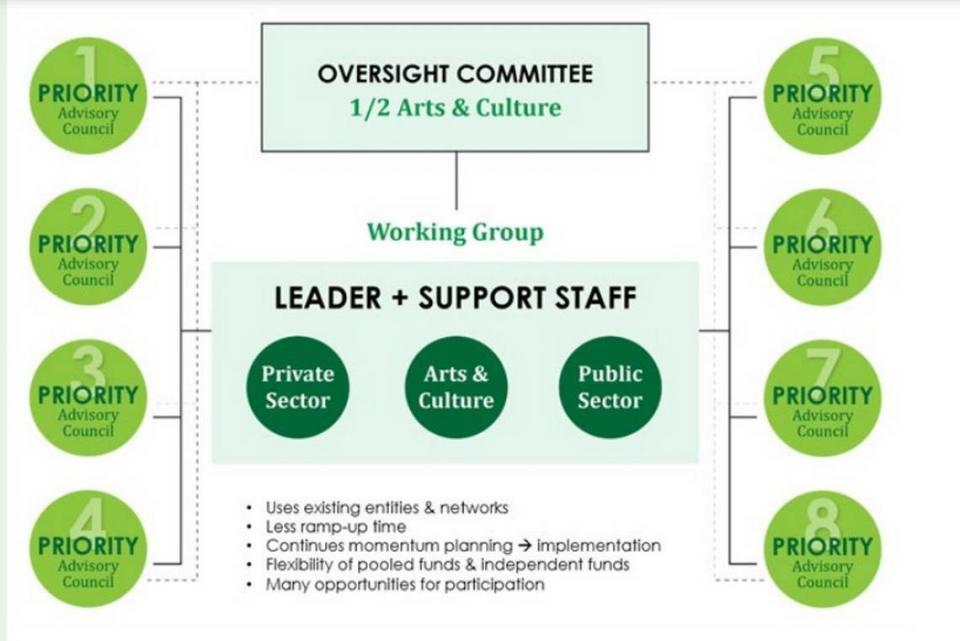

The plan offers a proposed new governance structure involving various community arts groups — including the Arts & Science Council, which was stripped of its role in disbursing city arts funds in this reorganization — and city and county representatives, but is short on specifics.

And though the plan emphasizes that the arts sector needs a dedicated revenue stream that should be a combination of public and private funds, it offers no details on how much money will be needed, where that money should come from or who will spearhead private fundraising efforts.

Priya Sircar, Charlotte’s first arts and culture officer who has guided the creation of the plan, said the conclusion from the 16-member board on who needs to commit funding is clear.

“The idea is that the public sector entities will really step up their funding in a big way, which is what Priority 1 of the plan is recommending,” she said, “while the private sector continues to fund as it has funded in a big way.”

Cyndee Patterson, the Arts and Culture Board’s co-chair, is more direct.

“It’s government,” she said. “I’m going to say this: We really anticipate the private sector will stay in the game like they always have. They’ve been very good corporate citizens.”

Although City Council accepted the plan, it still needs to determine how it will implement it — including how much money it will provide and where it will find the funds. That conversation is expected to occur during the council’s annual budget retreat in January, but it’s a major question still unanswered. And time — and money — are running out: The Infusion Fund’s contributions end in June 2024.

“We are now contemplating this future spending of unspecified amounts and with unspecified implications,” said council member Ed Driggs, who voted against accepting the plan. “Do we have to raise taxes? Can we divert money from other uses? That’s a conversation you need to have when you’re talking about committing funds.”

At least $12 million per year

Though it’s not written in the plan, Sircar and Patterson say the minimum expected to be needed is the current $12 million annual funding provided by the Infusion Fund.

The Infusion Fund, established in 2021, is made up of $4 million annually from the city, matched by $2 million from non-renewable American Rescue Plan Act funds and more than $6 million from private sector donations. It was to fund the arts sector for through the end of the 2024 fiscal year.

In the first year the Infusion Fund was in place, the Charlotte Ballet, Charlotte Symphony, Discovery Place and the Mint Museum received a combined $2.9 million from it. It helped — only the Mint Museum reported a loss in its 2021 tax returns.

“What I would say is I think $12 (million) is our baseline,” Patterson said. “And as we look at the plan, what I see is that $12 (million) won’t fund any of the newer, more robust pieces of the plan.

“We really would like to be able to know that once the funding is committed to from government, that it’s committed to with some way to grow it over time.”

According to Mayor Pro Tem Braxton Winston, who supported the Arts and Culture Plan, that’s one thing the city pledged — at least informally.

“The city has committed to continuing our public investment that has been going on over these past three years, and it will continue,” Winston said.

Krista Terrell, the president of the Arts & Science Council, has been asking for exactly that for years.

Moving away from ASC

In the process of reorganizing arts funding, the City Council shifted away from using the Arts & Science Council as a pass-through funding agency for arts. ASC was founded in 1958 as a Charlotte cultural hub, and has been the city’s pass-through arts funding agency for more than 40 years.

Terrell, who has announced she is resigning at the end of this year, said she has long advocated for an increased, dedicated revenue stream from the city to fund the arts. For fiscal year 2022, ASC requested $7 million from the city of Charlotte — a sharp increase from about $3 million the city had been contributing annually since 2005.

The city elected, instead, to create and divert its arts allocation to the Infusion Fund and reduce ASC funding — to $1.7 million in 2022 and $2 million in 2023.

“The way we looked at our investments and our priorities for arts and culture in the past was to basically cut a check,” Winston said at the Oct. 23 council meeting where the new plan was unveiled.

The city wanted more input into where the money was going, Winston and Driggs said — including ensuring that major arts organizations operating out of uptown facilities owned by the city are thriving.

“When it became a matter of public funding instead of private funding, we had to be more clear about what public interest was being served by the use of those taxpayer dollars,” Driggs said.

The new proposed governance structure would include leadership from the private and public sectors, and calls for flexibility in allowing for pooled and individual funds. That is, donors could direct funds to specific organizations of their choosing rather than one entity that disburses the money.

“The thing about the governance structure is that it is a kind of an evolution of what Charlotte-Mecklenburg has had before,” Sircar said. “It’s different in that you don’t see one centralized, single entity that is shouldering the entirety of advancing the plan.”

Tom Gabbard, president and CEO of Blumenthal Performing Arts, said it’s a structure that has worked in other cities across the country.

“What’s most important, though, is that there be a stream of government money that flows into arts and culture and that there be a stream of support from the business community,” Gabbard said. “But if that’s not centralized, that may actually be OK.”

Funding smaller groups vs. ‘historical European culture’

Of the eight priorities listed in the Arts and Culture Plan, six arguably reference supporting smaller, grassroots and individual artists or community art. That’s important, Patterson said, because “all boats rise on a rising tide.”

“My position is, if we start putting numbers around the things in this plan, of course the annually funded groups will also see the tide rise — if we have more money,” she said.

Driggs voiced concern in the Oct. 23 meeting that there was not enough explicit mention in the plan of supporting the city’s major arts organizations.

“One of the motivations for us to do that (increase city funding) was the fact that some of our legacy organizations were starving for funds and their existence was threatened,” Driggs said in the meeting. “In my mind, that was pretty key. I believe that those organizations and their tradition of acknowledging ‘historical European culture,’ I‘ll call it, is one of the things that marks Charlotte as a world-class city.”

Patterson said it has been a “balancing game” for the arts and culture board to remain committed to the priority of supporting historically marginalized arts groups and individuals, particularly those that identify as LGBTQIA+ and ALAANA (African, Latinx, Asian, Arab and Native American).

“We put our thumb heavily on the scale from the get-go of equity,” Patterson said. “So I’m sure Ed feels that maybe we didn’t do enough, and it’s not enough recommended.”

Later, Driggs told the Observer: “I wanted us to be clearer about the fact that one of our priorities with our public funding was to ensure the future viability of the programs that reside in these large venues that are funded by the city.”

Gabbard, who runs one of those major organizations in Blumenthal, said he sees the need for balance.

“The large organizations, I think, have reason to point out that they’re flagships that serve the entire region, and so it’s important that there be some funding there to support those programs,” he said. “It’s one thing for the city to build these facilities. It’s another thing to operate them; just building them is not enough. They’re not going to be strong, they’re not going to be meaningful to the community without programming money that brings them to life.

“But we also, thankfully, are much more aware of the needs of grassroots groups and individual artists. And I have seen a tremendous growth in that local art scene … and those needs are great.”

What’s next

According to a recently released arts and economic impact study conducted by Americans for the Arts, Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s arts and culture industry generated $453.8 million in economic activity in 2022. That’s why the city is so invested in ensuring that arts organizations and individuals succeed.

But City Council needs to grapple with the hard questions of funding and implementing the plan — and quickly. Sircar said it’s sweeping and broad for a reason.

“This isn’t a plan that’s written in stone,” she said. “It’s something that is meant to be a breathing, evolving thing over the course of the coming years.”

While the future of ASC’s involvement remains uncertain, both Patterson and Sircar said they’re hopeful that the organization will continue to be an important part of arts and culture governance, especially when it comes to grantmaking.

“We would love to use the infrastructure they have — we see them as partners,” Patterson said. “They already have systems in place, particularly for these individual artist grants and grassroots grants. So they know how to do it.”

But the main thrust of the Arts and Culture Plan is to emphasize that government needs to supply dedicated, consistent funds to support arts and culture in the community — even if exactly how and how much remains unclear.

The details, Winston said, can be specified later.

“What I do know is that the city of Charlotte is committed for the first time ever to investing — and prioritizing investment — to the arts and cultural sector in not just a status quo way, but in a growing way, over time,” Winston said.